A Thorny Path: School Desegregation in Baltimore

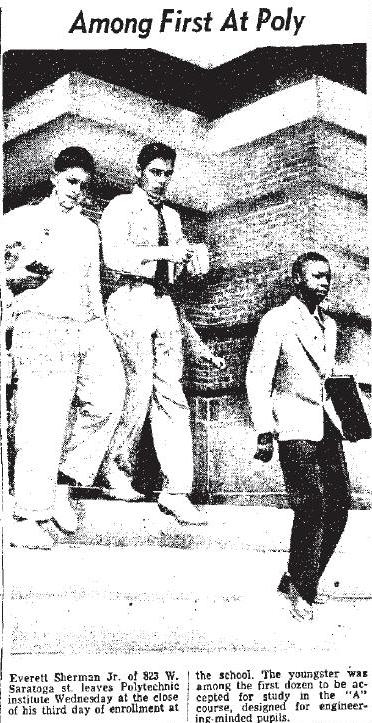

Protesting segregation of teacher training programs. National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Parren J. Mitchell far left. Douglass High School, Calhoun and Baker Street, Baltimore, Maryland, July 1948, Paul Henderson, HEN.00.A2-161, MdHS.

(This is the first part of a two part series – The second part of the story was posted in May 2014 and can be read here.)

May 17, 2014 marks the 60th anniversary of the Supreme Court ruling on Brown vs. Board of Education. Activism in Baltimore and throughout the state of Maryland had been building toward a case for integrated public education for many years prior to the decision.

Maryland has almost always occupied an ambivalent position on racial matters. Despite being a slave state, it never seceded from the Union and was home to nearly as many free as enslaved African-Americans in the antebellum period. Public schools for non-whites were officially established in 1866 without Federal intervention or the influence of a black-majority legislature. The General Assembly peppered its decision with condescending rhetoric, reflecting the anxiety that many whites had about the newly liberated population in their midst. The primary justification was that “whether the child be of Indian or African, European or Asiatic descent; his ignorance will be a blight and his vice a curse to the community in which he lives.” Education would ideally serve to keep African-Americans out of the almshouse and the penitentiary. There was certainly no discussion of interracial schools, as this class of people “could not mingle with the white children.” (1)

The Colored High and Training School was founded in 1882. From 1900 to 1925 it resided in this building on the corner of Pennsylvania Avenue and Dolphin Street. In 1925 the school relocated to Calhoun and Baker Street and was renamed Frederick Douglass High School.

School #450-A. Pennsylvania Avenue and Dolphin Street. 1893, Baltimore City Buildings Photograph Collection, PP236.1462, MdHS. (Reference Photo)

Blacks in Baltimore were particularly eager for public support of their children, who had primarily been served by a network of private and parochial schools. Organizations such as the Baltimore Association for the Moral and Educational Improvement of the Colored People had been petitioning the city for financial backing, and were finally successful in 1867. Many of the existing schools were turned over to the public system, and large numbers of local African-Americans quickly took advantage of the opportunity. Black leaders still had to battle for control of the Colored Schools, which were initially staffed exclusively by white teachers. Prominent lawyer Everett J. Waring and the Reverend Harvey Johnson led efforts to gain employment for black teachers, while also lobbying for better facilities and more advanced programs for students. The first “Colored High School,” which would later become Frederick Douglass High School, was established in 1882. Black teachers were hired as early as 1889, and by 1907 the student body and faculty was completely segregated. (2)

From 1913 to 1967, Poly was located at this building at the corner of North Avenue and Calvert Street.

School #403. Polytechnic Institute. North Avenue and Calvert Street. 1909, Baltimore City Buildings Photograph Collection, PP236.1423, MdHS. (Reference Photo)

The dual Baltimore school systems would operate semi-autonomously for nearly 50 years, before demographic and social changes led to more radical reforms. World War II brought a massive influx of new residents, both black and white, to Baltimore. Hoping to gain employment in the city’s industries, these primarily southern and Appalachian migrants arrived in an already crowded urban center that was ill-prepared for them. African-American communities bore the brunt as they were already hemmed in by segregation, and white Baltimoreans protested vehemently against efforts to allow for its geographic expansion. Residential and educational facilities for black Baltimoreans were woefully insufficient as the city’s population reached nearly one million in the late 1940s. Former teacher and administrator Enolia McMillan would later remark that:

“Our buildings were outmoded, inadequate; equipment was unsatisfactory… We never received new textbooks in elementary or high school. We got the hand-me-downs, and when they got ready to put in new textbooks in the other schools, they sent the old textbooks over to us.” (3)

Despite notable gains, such as the equalization of teacher pay and the inclusion of an African-American on the school board, local schools struggled to serve the nearly 50,000 black students. NAACP Director Lillie May Jackson would claim that Booker T. Washington Junior High had nearly twice as many students as it was designed to house, while many of the other segregated schools were forced to use portables or operate on shifts due to overcrowding. Many of the buildings had formerly been used as white schools, and were deemed unfit for use before becoming black schools. (4) Leaders responded to the crisis by pushing for greater control over the colored schools, but also proposing that integration could be a part of the solution. As early as 1945, Juanita Jackson Mitchell questioned why Chinese students “are permitted to enter Polytechnic Institute, where Negroes can’t enter.” (5) In fact, that school would become central in the local effort to integrate the educational opportunities for city children. Owing to its exclusive A-Course and specialized engineering curriculum, Baltimore Polytechnic Institute or “Poly” was one of the most highly esteemed public schools in the state. Graduates of the advanced program could expect to be accepted into the best colleges, with many even entering engineering schools as sophomores.

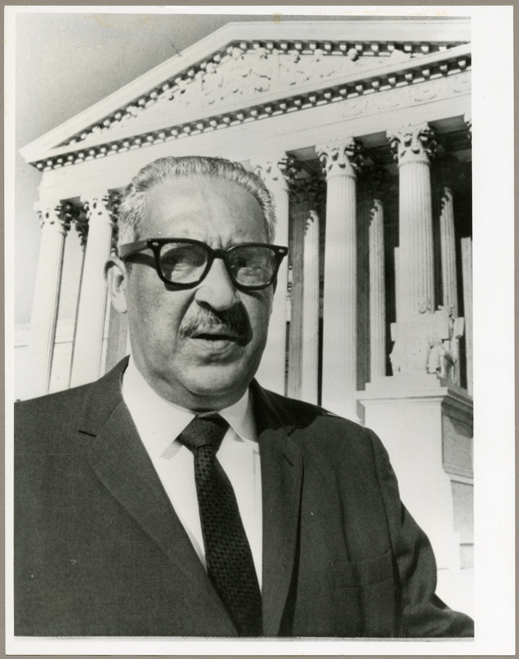

Thurgood Marshall in front of the U.S. Supreme Court Building, Washington D.C., 1967, courtesy News American Library, Portrait Vertical File, MdHS.

In the spring of 1952, a biracial coalition of organizations including the NAACP and the Baltimore Urban League began to discuss plans to integrate Poly. By focusing on the “separate but equal” provision of the Fourteenth Amendment, the Coordinated Committee on Poly Admissions (CCPA) was following the model that Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP had employed throughout the 1930s and ’40s to integrate the University of Maryland’s various graduate programs. In the first of many separate cases, Marshall successfully challenged the exclusionary policy of the University’s Law School, gaining admission for Donald Gaines Murray in 1936. As in those earlier cases, activists had to establish that there was no comparable program in the local colored schools. They were prepared when the school board ended up proposing the development of a similar advanced program at Douglass High School, which could have potentially derailed the legal argument. Another major sticking point was the city ordinance which legally required separate schools for white and Negro students. The CCPA needed to gain allies and find qualified African-American students to apply to the all-male school. After months of secretive planning and outreach, 16 boys applied for Poly’s A-Course on July 12. However, the hearing would not take place until September 2, 1952.

On that day, nine members of the school board, a mixture of business leaders, higher education officials, and community members, were set to deliberate on the subject. Representatives of the Urban League and the NAACP were in attendance to make their pleas for integration. The proposal to duplicate Poly’s program at Douglass was strongly opposed by many of the participants. One of the League’s chosen speakers was Robert H. Roy, assistant dean of the Johns Hopkins University School of Engineering. While he maintained that admissions offices from his and other universities would eventually accept Douglass graduates, those students “would find the path a thorny one.” William H. Lemmel, superintendent of public instruction, agreed that while possible it would take many years for a substitute program to build up the prestige that Poly’s A-Course had developed.

Thurgood Marshall provided more direct opposition, stating that the Douglass plan was “At best a gamble – (and) a gamble is not what I consider equality.” He would further cite the psychological and sociological evidence of segregated schooling’s negative effects on students, much of which would later form his argument in the Brown case. (6)

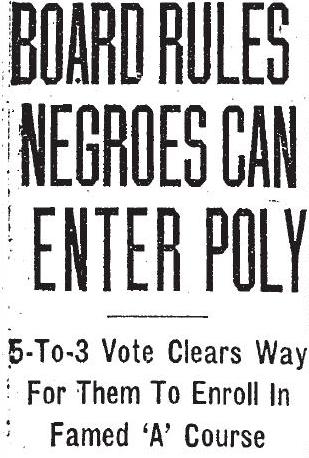

Board member Walter Sondheim would later recall that Marshall “got quite emotional about the case and suggested that the school board was afraid… most of us thought at the time that he almost killed the case.” Sondheim was convinced that the board members’ generally liberal view toward the issue would have led most of them to support the integration plan. (7) Despite some opposition during the four-hour session, most notably from Poly’s Alumni Association, the board went on to vote 5-3 in favor of the students’ admission to the A-Course. Twelve* African-American boys entered the school that fall. While their experiences ranged from subtle discrimination to open acceptance, there was little of the public hostility that would characterize desegregation cases further south.

The NAACP almost immediately followed up this victory with similar attempts to integrate the all-female Western High School and the Merganthaler School of Printing (Mervo). These legal cases would follow the same reasoning as that against Poly. Both schools had unique programs, which made them suitable targets under the separate but equal statute. Despite the victory with Poly’s program, both proposals were rejected by the school board in early 1953. In the Merganthaler case, there was a more legitimate argument that Douglass and Dunbar had printing programs with “certain features in common” with the white school. Furthermore, an “identical” program was being developed for the new Carver Vocational-Technical school, which would serve African-Americans in the city. (8) In the Western case, board members were apparently unconvinced that an all-girls program was “inherently superior to coeducation.” Despite having an A-Course, the liberal arts track at the school was also not as explicitly specialized as Poly’s engineering program, and therefore could be more easily replicated at Douglass. The NAACP was prepared to take both cases to court. However, all of the involved parties were aware that school desegregation cases were already being deliberated in the Supreme Court. Baltimore’s City Solicitor Thomas Biddison requested that the suits be put on hold, since the resulting decisions could make additional legal action unnecessary. (9)

The NAACP legal team, led by Baltimore native Thurgood Marshall, had reached the U.S. Supreme Court with the Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka case in early 1953. The original suit was filed in Kansas, and again challenged the contention that segregated public schools could be considered equal. The case was ultimately settled the next spring, with a unanimous 9-0 decision in favor of the plaintiffs. Much of the argument rested on the psychological aspects of the current system, specifically that it “generates a feeling of inferiority as to [black children’s] status in the community.” Furthermore, the justices determined that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” (10)

However, the question still remained: how would states and municipalities implement the decision, if at all? Baltimore was perhaps in as good a position as any southern city to deal with these momentous implications. Local officials were certainly well aware that the case was pending and the experience at Polytechnic had shown that a relatively smooth transition was possible. Elizabeth Murphy Moss would later recall, “When the Court handed its decision, already everything was moving … Because there had been this foresight in planning and there had been established a rapport between the school officials who wanted to do the right thing.” (11) But would that good will and planning be enough to avoid the potential difficulties of desegregating a whole system with more 140,000 students? (David Armenti)

Part Two of the story can be read here.

David Armenti is the Student Research Center Coordinator at the Maryland Historical Society.

Footnotes:

*This blog post originally stated that “Fifteen African-American boys entered the school that fall.” The post was updated in June 2022 to reflect additional research showing that the total number should be “Twelve.”

(1) Proceedings and Acts of the General Assembly, 1866, Volume 107, pp. 487-489.

(2) Bettye C. Thomas. “Public Education and Black Protest in Baltimore, 1865-1900.” Maryland Historical Magazine. Vol. 91, No. 3, Fall 1976.

(3) Enolia McMillan. OH 8110. Interviewed by Richard Richardson, April 6, 1976. McKeldin-Jackson Project, Maryland Historical Society Library.

(4) Howell S. Baum. Brown in Baltimore: School Desegregation and the Limits of Liberalism. (Ithaca: CornellUniversity Press, 2010). pp. 44-45.

(5) “Negroes Request School Control,” The Baltimore Sun. 16 February, 1945. Read more about Chinese integration into Baltimore Schools, “Is He White or Colored.”

(6) “Board Rules Negroes Can Enter Poly,” The Baltimore Sun. 3 September, 1952.

(7) Walter Sondheim. OH 8044. Interviewed by Francis Collette, October 19, 1971. Maryland Historical Society Library.

(8) “Printing School Rejects 4 Pupils,” The Baltimore Afro American. 14 February, 1953.

(9) Baum, Brown in Baltimore, pp. 60-64.

(10) Ibid, p. 65.

(11) Elizabeth Murphy Moss. OH 8110. Interviewed by Leroy Graham, July 13, 1976. McKeldin-Jackson Project, Maryland Historical Society Library.