A Tribute to Annie

Inspired by the Craftsmanship of Annie G. Dunton

by Barbara Meger, Museum Volunteer

I am fascinated by anything related to textiles—costume, needlework, lace, couture fashion, dressmaking, quilting, etc. As a volunteer curatorial assistant at the Maryland Center for History and Culture, I am privileged to see and to examine myriad specimens as I assist MCHC staff to prepare them for exhibition or storage.

One such discovery (1953.127.21) is the many pieces of an unfinished quilt (Figure 1)—some of which are currently on display as part of the current MCHC exhibition, Wild and Untamed—Dunton’s Discovery of the Baltimore Album Quilts—assembled by Annie G. Dunton (1833-1893) sometime during the 1880s.

A talented seamstress and needleworker, she was an early pupil of the Philadelphia School of Art Embroidery. Her tiny pieces of silk are meticulously cut into 1¼ʺ x 4¼ʺ strips, then five strips are arranged in a dark-to-light color gradation and joined to form a 4¼ʺ square or block. These blocks are arranged horizontal to vertical and attached to each other to form strips (Figure 2) which ultimately would have been sewn together to create the quilt.

Annie G. Dunton’s son, Dr. William Rush Dunton Jr., is known as the father of occupational therapy. He recognized that the repetitive nature of quilting, which also allowed for self-expression and creativity, had a positive effect for those of his patients at Sheppard and Enoch Pratt Hospital in Baltimore who were suffering from mental distress.

These pieces came into the MCHC collection in 1953 with an attached note, presumably by Dr. Dunton: “The pieces of silk in this box were mostly collected by Annie G. Dunton for a ‘Tea Box’ piece of work, parts of which are also in this box and a number, sewed together, are in the chest containing quilts.”* A search for other specimens of “Tea Box” quilts yielded a totally different design utilizing tiny individual squares of fabric rather than strips. It is easy to see why the contemporary quilt experts I consulted put this design in the family of Rail Fence or Split Rail Fence quilts because of its resemblance to the zigzag rail fences once seen in the countryside.

Further research noted that because this design “uses only strips, it was most likely created for more utilitarian purposes,”** meaning it could be cut from fabric scraps rather than special fabrics needed for the decorative whole cloth and applique quilts also popular at this time. Indeed, among the cut pieces are scraps of fabric, some with their intact selvage edges, waiting to be cut into shape. Dr. Dunton mentioned that his mother would sometimes cut up his old school ties to use in her quilts.

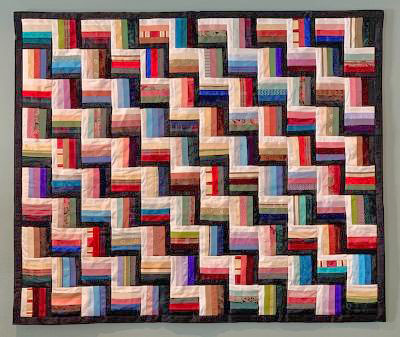

Annie’s pieces and her workmanship intrigued and inspired me to create a wall hanging. Although I do not consider myself an expert quilter, I’ve made several simple quilts over the years and am familiar with basic techniques. I knew I wanted to stay close to what Annie had planned, but I also wanted to give it my own signature. Like Annie, I used only silk fabrics. Luckily, my personal “stash” of fabrics contains an extensive assortment of silks left from previous projects, plus some treasured Scalamandré salesman samples. I chose to cut the exact size 1¼ʺ x 4¼ʺ strips from my fabrics and join them into the same five-strip blocks ranging in color from dark to light. The next step was to join the 120 blocks into strips that would then be joined to create my 10-block by 12-block wall hanging.

Figure 4. Construction with the sewing machine.

Figure 3. Preparation for “A Tribute to Annie.”

I marveled at the precision of Annie’s tiny strips, each cut exactly with the weave of the fabric. Today that is an easy achievement with the ready availability of rulers, rotary cutters, and mats (Figure 3). Instead of short 4¼ʺ pieces, modern quilters would use a technique known as strip-piecing and sew together five long 1¼ʺ strips of fabric in the dark to light arrangement, then cut multiple (and identical) 4¼ʺ square blocks. I chose instead, like Annie, to sew the 600 pieces together individually so that each block is unique. Unlike Annie, however, I used a sewing machine (Figure 4) and completed the task in a matter of days rather than the weeks or months it must have taken Annie to precisely hand-stitch each of the ¼ʺ seams making up her blocks.

At about the same time I got started with quilting some 40 years ago, I was introduced to English smocking, an embroidery technique usually associated with little girls’ dresses. I realized at that time there was not room in my life for both, so quilting faded into the background as I spent subsequent years designing, teaching, and writing about English smocking. To give the wall hanging my own stamp, I knew that I had to somehow incorporate smocking and came up with small designs that would fit as a few of the 1¼ʺ x 4¼ʺ strips. I like the texture they add to the piece (Figure 5).

Figure 6. Stitching “in the ditch” to secure the quilt layers.

Figure 7. “A Tribute to Annie.”

It finally came time to put everything together. Traditionally, a quilt is formed of two layers of fabric with an insulating layer of cotton or wool batting sandwiched in between. The verb “to quilt” is the act of stabilizing these layers so that they won’t shift. One method is to “tie” the layers together with individual knotted stitches; another is to secure the layers with multiple rows of stitching in some sort of pattern, either by hand or machine. I chose a third technique known as “stitching in the ditch,” that tiny indentation made on the outer surface when two pieces of fabric are seamed together (Figure 6). By following the pattern of the zigzag lines formed by the blocks, this stitching is virtually invisible and allows the flow of color and design to move without interruption.

Whenever I look at my completed project, now hanging on a wall (Figure 7), I think of Annie G. Dunton. Her inspiration has provided a means to help keep me grounded and occupied during today’s difficult times—just the sort of therapy recognized by her son, Dr. Dunton.

Postscript: I overestimated the number of strips of fabric I would need, so am still busily stitching companion pillow covers and anything else I can think of to use them up!

I would like to thank quilt experts Allison Aller, Mimi Dietrich, and Dawn Ronningen for their insight.

*MCHC 1953.127.21

**www.blog.stitchinheaven.com