A “Triumphal” and “Monster” Parade: The June 1912 Baltimore Suffrage Parade

One hundred nine years ago this month, Maryland suffragists took to the Baltimore streets in a momentous march for women’s voting rights. In this blog post, Emma Z. Rothberg, Maryland Center for History and Culture’s Lord Baltimore Fellow for 2019/2020, explores the 1912 march and her experience diving into primary resource materials within the MCHC’s H. Furlong Baldwin Library.

As a born and bred New Yorker, the word “parade” used to conjure up images of blocked streets, diverted buses, and an inability to get anywhere I needed to be efficiently. Parades were something I actively distanced myself from, choosing to walk blocks out of my way to avoid the crowds rather than try to wade my way through the throng. And yet, starting in 2016 I found myself sitting in the H. Furlong Baldwin Library at the Maryland Center for History and Culture not only actively seeking out information on parades in Baltimore, but reevaluating my relationship with these large-scale events.

As I sat in the library combing through newspaper articles, photographs, and the materials of parade organizing committees, I was immediately drawn into the earnestness with which people planned and covered these parades. People believed in the power of these spectacles—the power to promote, to celebrate, to change minds. Newspapers and organizers spoke in ebullient and (to my twenty-first century ear) flowery language about how parades were the best means for accomplishing their goals. Beyond the language, the imagery of these parades was spectacular.

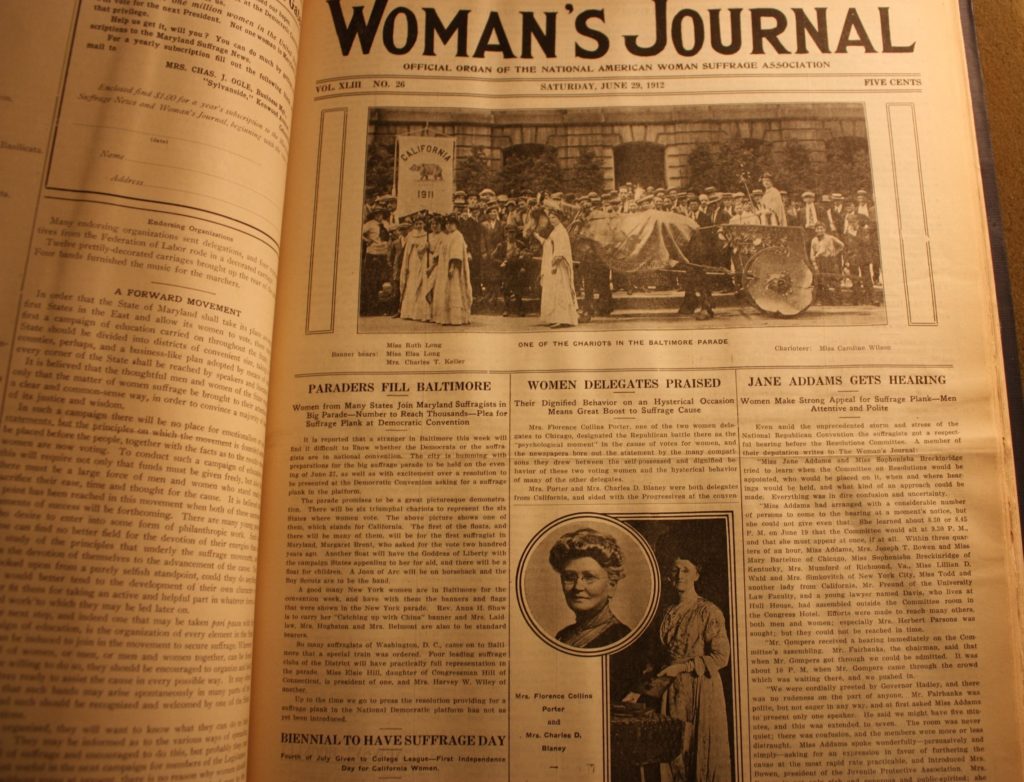

It was when I was combing through the Library’s collection of Maryland Suffrage News (MSN), a companion to the Woman’s Journal produced by the National Association of Woman Suffrage (NAWSA), that my attention was piqued by reprinted images of participants in various suffrage parades and events in 1912. There were women in costume, women on floats, women carrying banners. Why did they choose these images as the best means to advocate for their right to vote?

Maryland women had taken part in successful suffrage parades in New York City, but they were inspired to host one of their own in 1912. The MSN on May 18 told readers that the summer of 1912 “constitutes a unique opportunity for the suffragists of Baltimore, of Maryland and of all the States in the Union to draw attention to the fact that we are living in a lopsided democracy.” 1912 was an election year. The Republican National Convention was in Chicago, and suffragists were planning a parade. The Democratic National Convention was coming to Baltimore in June. The MSN argued that the most effective way to show women’s desire for the vote was if people from all over the United States came to Baltimore to march. The MSN argued, “this is the first time at a Democratic Convention that women have so far aroused from the training and the lethargy of centuries as to demand consideration as human beings. And we want the fact to be impressive.”[2]

For Maryland suffragists, a parade would be the visualization of the more equitable democracy they desired. By attaching themselves directly to political parties, women’s suffrage advocates were explicitly making claims on the democratic process. For the participants, the parade was an earnest and vital vehicle for women to prove they were equal members in a democracy. This parade allowed participants to take advantage of Baltimore’s elevated position as a space of national interest representing the democratic process to boost their own position.

As I continued to flip through the pages of MSN, furiously taking notes, I kept seeing disagreement. One objection was that a convention week was not ideal for a suffrage parade as the attending men would be too busy with other business. Another fear was that such a big stage could result in a big failure if not enough women participated. Maryland suffragists again emphasized the unique opportunity of the convention week, arguing that a parade would give the Democrats “an opportunity to prove the sincerity of their statements about ‘democracy.’”[3] Apparently these arguments worked, for the MSN reported on June 1, “the wet blanket thrown over our parade plans last week seems to be rather drying off—at least, the heat of enthusiasm underneath is such that is forced to dry off, and we shall emerge triumphant.”[4]

On June 28, 1912, an estimated 1,000 suffragists began their march west on Monument Street to Park Avenue and then around the Convention Hall in the Fifth Maryland Regiment Armory on Hoffman Street as roughly 15–20,000, or 50,000 according to the MSN, spectators watched from the sidewalks.[5] I realized the parade had probably passed right by the building in which I was sitting. The parade began with a “cordon of mounted policemen” and the parade’s female marshals on horses. The Baltimore Sun reported the police were there to “wreak vengeance on persons who had been promiscuous in threats to hurl tomato cans, aged eggs, et cetera, at the paraders.”[6]

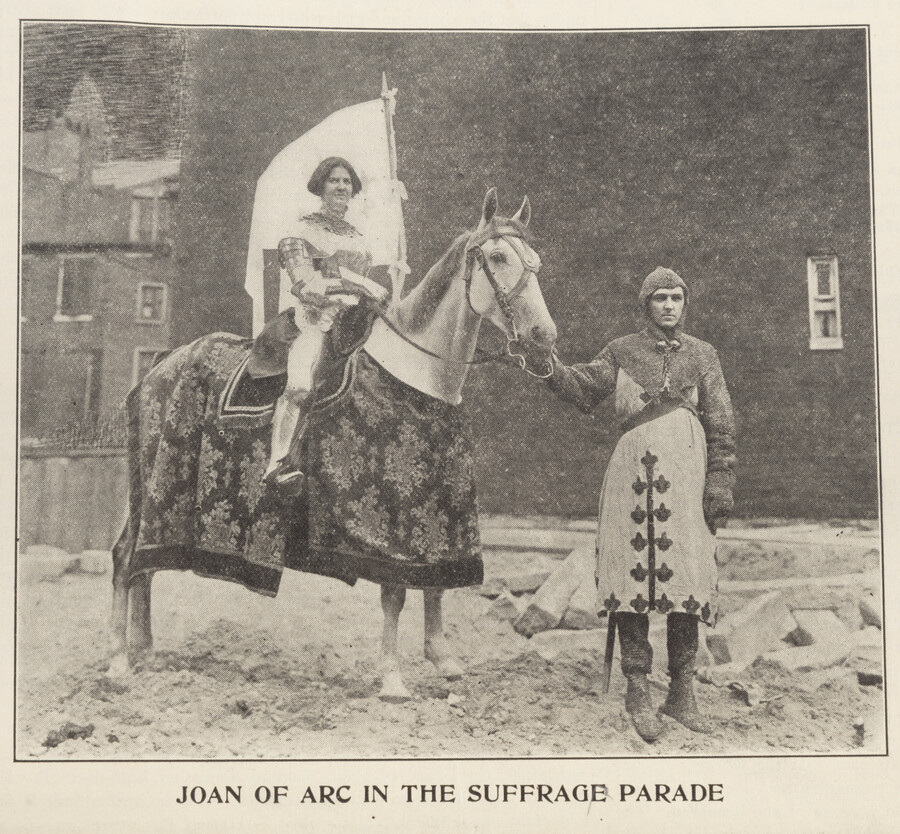

As I continued to flip through the Library’s holdings of MSN, I found my first photograph of a Joan of Arc. The parade was led off by Miss Ida Baker Neepier dressed as Joan, “with her steel armor scintillating in the glare of the electric lights” she “waved her mailed hand from her seat on a show-white charger.”[7] Joan was a favorite icon for the American suffrage movement because she represented, to suffragists, a woman fighting the good fight against men who sought to oppress her. (Though suffragists did ignore her eventual torture and execution.) That Joan of Arc was historically removed from the twentieth-century suffrage movement made her image less threatening to men; women in medieval-style armor did not evoke the same gendered fears as if women paraded in more contemporary military uniforms. “Joans” appeared not only in the 1912 Baltimore parade, but in New York City, Philadelphia, and Boston suffrage parades. Most famously, leading suffragist and women’s labor advocate Inez Milholland (who was called “the most beautiful suffragette” by The Washington Post) led off the 1913 Washington, D.C., suffrage parade dressed as Joan of Arc.[8]

Another prominent visual of the parade were floats. There were floats dedicated to mothers, “Baltimore’s beauties” driving Roman chariots representing suffrage states, and the Goddess of Liberty.[9] Another float was dedicated to Margaret Brent, who Maryland suffragists claimed was the first women to “seek the franchise.” In the 1640s, Margaret Brent appeared in front of the Colonial Assembly and asked Lord Baltimore himself for a vote as a landowner.[10] The float, decorated in colors of Maryland (black and orange), had Miss Kate Ernst dressed as Brent “at the feet of Lord Baltimore (Mr. Frank F. Ramey), enthroned on high, still seeking the right of franchise.”[11] The Margaret Brent float made women’s role in the history of the United States central and emphasized that women had been fighting for the vote for centuries. In the end, Maryland was named for a woman.

I was most struck by the description of the Just Government League of Maryland’s presentation. Following behind the chariot for Utah, the “members of the Just Government League of Maryland [wore] paper shackles, designating their bondage to the tyranny of man.”[12] Another description stated the paper shackles showed “how man has bound woman in the affairs of the nation.”[13] Women were done being subtle. I was desperate to find an image, but unfortunately none accompanied the press descriptions. I am still hoping to find one.

The MSN deemed the 1912 Baltimore suffrage parade a success, calling it “The Best Parade Ever Held in Maryland.”[14] Press coverage unanimously agreed the parade was orderly, smooth, spectacular, and went a long way in convincing the crowds and the DNC of the suffrage cause. The Woman’s Journal used the terms “monster” and “triumphal” a number of times to describe the size and success of the parade. Yet the Democratic Party did not adopt suffrage in its 1912 political platform.[15]

While it did not convince the Democratic Party, the 1912 parade did help convince Maryland suffragists and the press of the advisability of parades for the movement. The MSN argued by parade’s end, “none were near to question the advisability of a parade or the ability of suffragists to unite for the good of the cause.”[16]

As I finished reading through the Maryland Suffrage News’s description, I found myself agreeing with the organizers—spectacular parades could change minds. While I will not argue the Nineteenth Amendment passed because of the proliferation of suffrage parades across the United States, I will argue parades went a long way towards persuading people—especially the men who could vote on the subject—that women were fit and capable of holding their own in the public arena. They did not need to be shielded or protected by men; they needed to be given their own voice. The power of these early suffrage parades to persuade carries resonance with us today. Particularly as we emerge from the COVID-19 pandemic and venture outside again, I will view my relationship with the theater of the streets in quite different ways.

Emma Z. Rothberg is a PhD Candidate in History at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill who focuses on urban, cultural, and gender history in the nineteenth- and early twentieth- century United States. Her dissertation examines the cultural practices of urban democracy and identity in American cities at the turn of the twentieth century. She is currently the Co-Director of UNC’s Digital History Lab and serves as the U.S. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg Predoctoral Fellow in Gender Studies at the National Women’s History Museum. Originally from New York City, Emma received her BA from Wesleyan University and MA from UNC-Chapel Hill.

[1] “The Suffrage Parade,” Maryland Suffrage News (Baltimore), Vol.1, No.10, June 8, 1912.

[2] “Suffrage Parade Planned for Baltimore—Women Will March in National Democratic Convention,” Maryland Suffrage News (Baltimore), Vol.1, No.7, May 18, 1912.

[3] “Suffrage Parade,” Maryland Suffrage News (Baltimore), Vol.1, No.8, May 25, 1912.

[4] “The Suffrage Parade,” Maryland Suffrage News (Baltimore), Vol. 1, No. 9, June 1, 1912.

[5] “1,000 Suffragettes Parade,” New York Times (New York),June 29, 1912; “The Baltimore Parade. A Brilliant Success on a Perfect Evening—Crowds, Enthusiasm and Good Nature Along the Line of March—‘The Best Parade Ever Held in Maryland,’” Maryland Suffrage News (Baltimore), Vol.1, No.14, July 6, 1912.

[6] “March Like Men,” The Sun (Baltimore), June 29, 1912.

[7] “March Like Men,” The Sun (Baltimore), June 29, 1912.

[8] Allison K. Lange, Picturing Political Power: Images in the Women’s Suffrage Movement (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2020), 170; Mary Dockray-Miller, “Why Did the Suffragists Wear Medieval Costumes?” JSTOR Daily, March 4, 2020, accessed June 15, 2021, https://daily.jstor.org/why-did-the-suffragists-wear-medieval-costumes/.

[9] “1,000 Suffragettes Parade,” New York Times (New York),June 29, 1912; “March Like Men,” The Sun (Baltimore),June 29, 1914; ““The Baltimore Parade. A Brilliant Success on a Perfect Evening—Crowds, Enthusiasm and Good Nature Along the Line of March—‘The Best Parade Ever Held in Maryland,’” Maryland Suffrage News (Baltimore), Vol.1, No.14, July 6, 1912.

[10] Margaret Brent continued to be an important figure for suffragists in Maryland. When the Just Government League held a “hike” throughout Maryland counties with their “pioneer schooner” (a covered wagon) in 1915 to convince people to vote for suffrage, they dedicated the “schooner” to Margaret Brent; See Maryland Suffrage News coveragein 1915 for more on the Margaret Brent “hike.”

[11] “The Baltimore Parade. A Brilliant Success on a Perfect Evening—Crowds, Enthusiasm and Good Nature Along the Line of March—‘The Best Parade Ever Held in Maryland,’” Maryland Suffrage News (Baltimore), Vol.1, No.14, July 6, 1912.

[12] “March Like Men,” The Sun (Baltimore),June 29, 1912.

[13] “1,000 Suffragists March,” New York Tribune (New York),June 29, 1912

[14] “The Baltimore Parade. A Brilliant Success on a Perfect Evening—Crowds, Enthusiasm and Good Nature Along the Line of March—‘The Best Parade Ever Held in Maryland,’” Maryland Suffrage News (Baltimore), Vol.1, No.14, July 6, 1912.

[15] Democratic Party Platforms, 1912 Democratic Party Platform Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project, accessed June 15, 2021, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/273201.

[16] “The Baltimore Parade. A Brilliant Success on a Perfect Evening—Crowds, Enthusiasm and Good Nature Along the Line of March—‘The Best Parade Ever Held in Maryland,’” Maryland Suffrage News (Baltimore), Vol.1, No.14, July 6, 1912.