Baltimore’s Pursuit of Fair Housing: A Brief History

In this blog post, Maryland Center for History and Culture (MCHC) guest contributors David Armenti, Director of Education, and Alex Lothstein, Museum Learning Manager, examine Baltimore’s history of housing discrimination and the pursuit of fair housing.

In the spring of 2020, the Baltimore City Office of Equity and Civil Rights reached out to collaborate with the Maryland Center for History and Culture for the virtual Fair Housing Festival. Staff from MCHC created a short video highlighting Baltimore’s long history of housing discrimination, which began both a partnership between the two organizations and an increased focus by MCHC to make the history of race-based housing discrimination more public. MCHC staff also participated in public programs and related interviews in a continuation of this collaborative partnership. In April of 2021, MCHC partnered with the Baltimore City Office of Equity and Civil Rights once again, along with the Baltimore Office of Promotion & the Arts, and the Baltimore National Heritage Area for this year’s Fair Housing Festival. MCHC used its collections to create an exhibit focused on housing discrimination for the outdoor exhibition entitled “Baltimore’s Pursuit of Fair Housing: A Brief History.” This exhibition will be on display at the Parks and People Foundation site near Druid Hill Park in Baltimore throughout April 2021.

Staff members for the Maryland Center for History and Culture used collections from the H. Furlong Baldwin Library to research, write, and provide materials and images for the exhibit panels. Some of this research and some of these images are included in the text below.

The public, K-12 educators, and students can access the following short video for an introduction to housing discrimination history and consequences of redlining in Baltimore: https://vimeo.com/434469938 as well as a longer discussion here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_4__O8vxPLE

Before the Civil War, Baltimore housing was reasonably diverse, with white and Black residents living around each other. However, white Baltimoreans tended to live on main streets while Black Baltimoreans primarily lived along alleyways. Following the Civil War, an increase in Black and European immigration to Baltimore, coupled with new public transportation options and the Great Baltimore Fire of 1904, began to lead to white middle-class flight. During the early 1900s, white Baltimoreans started using housing ordinances, homeowners associations, and block-busting to discriminate against and segregate Black Baltimoreans. Initially as white residents moved out of downtown Baltimore, followed by some ethnic groups, such as Jewish immigrants, there were no official housing segregation policies that stopped wealthy and middle-class Black Baltimoreans from following the same trajectory. Nevertheless, most realtors did not sell to Black families. If a Black family bought a house in a white neighborhood, the white property owner most likely sold it themselves.

In 1910 a white homeowner sold the property at 1834 McCulloh Street to W. Ashbie Hawkins, a prominent Black attorney. This sale broke the color barrier of the 1800 block of McCulloh Street. However, the subsequent rental to his law partner, George McMechen, led to white backlash and began a series of official and unofficial housing discrimination policies in Baltimore.[1]

Unofficially, this sale began a home-selling pattern in which white Baltimoreans would sell to Jewish homebuyers. Jewish homeowners would then sell, only if their neighborhood or block’s market was in a slum, to Black Baltimoreans. Once Black home buyers broke the block, many white homeowners would freely sell to Black home buyers or renters. Although this line of succession primarily took place in the old West Baltimore neighborhoods of Upton and Druid Heights, this block-breaking scared white homeowners and government officials throughout Baltimore.

One of the first official policies was Baltimore City Ordinance 610, known as the West Plan – named after Councilman Samuel West. This ordinance, passed by the City of Baltimore in December of 1910, stated that no Black resident could move on to a block in which more than half of the residents were white and vice versa. The West Plan did have a provision stating that existing conditions would not be disturbed, and no homeowners needed to move out of their neighborhood.[2] While Ordinance 610 was the first of three race-based housing ordinances in Baltimore, many cities across the United States and even the world modeled similar discriminatory laws after the West Plan. Nevertheless, the Supreme Court deemed civil government-instituted housing segregation laws unconstitutional in 1917 with Buchanan v. Warley.[3] However, in its seven years of existence, Ordinance 610 led to race-based predatory lending policies and housing lines dictated by race that still exist today.

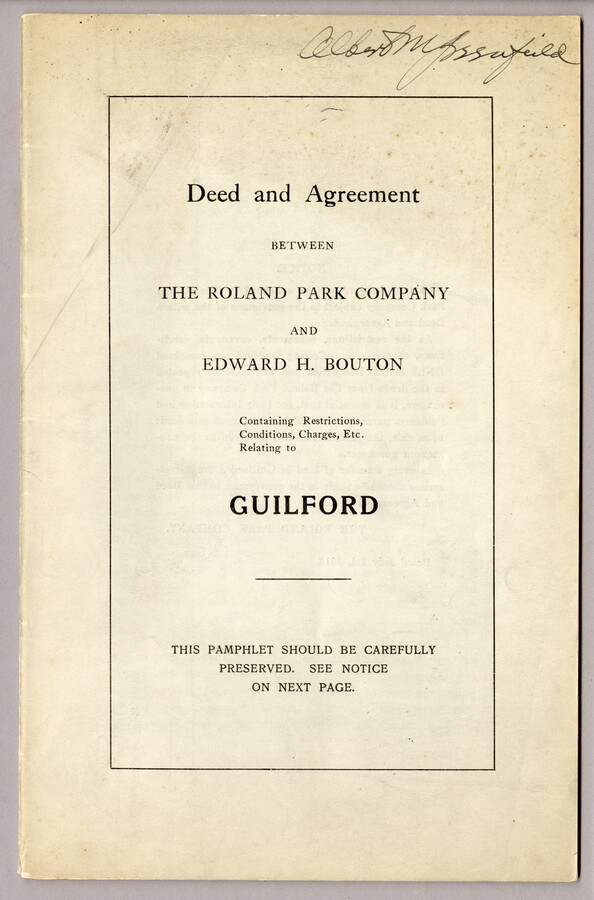

While Ordinance 610 was a government-sponsored housing segregation law, many private Baltimore communities instituted community covenants that restricted Black Marylanders from moving into the neighborhood. One example was the Guilford neighborhood, planned and designed by the Roland Park Company. In a section within the Roland Park Company’s Guilford Neighborhood Covenant from 1913 entitled “Nuisances,” a provision stated that “at no time shall the land in said tract or any part thereof shall, or any building erected thereon, be occupied by any Negro or a person of Negro extraction.” The covenant did make an exception for Black domestic servants to white families.[4]

Covenants and housing ordinances forced many Black families into neighborhoods that consistently suffered from unequal resources and lack of investment. This discrimination led to lower home values and challenges in accumulating wealth. However, some neighborhoods for upwardly mobile Black families, such as Morgan Park or Cherry Heights, advertised as having lots as beautiful as Roland Park.[5] The second was, coincidentally, established by a realty company represented by lawyers George McMechen and W. Ashbie Hawkins. It was not until 1948 that the Supreme Court ruled in the Shelly v. Kramer case that restrictive private covenants were unconstitutional and violated citizens’ 14th Amendment rights.[6]

In 1937, the Federal Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) published its Residential Security Map of Baltimore. This map graded the lending risk factors and desirability of neighborhoods in Baltimore and many other American cities. While initially part of the New Deal’s National Housing Act of 1934, intended to help prevent foreclosures, the maps soon became a symbol of race-based housing discrimination.

You can view this Residential Security Map from 1937 via Johns Hopkins Sheridan Libraries Digital Collections: https://jscholarship.library.jhu.edu/handle/1774.2/32621.

Areas in Green (Grade A) were the most desirable, followed by Blue (Grade B), Yellow (Grade C), and finally Red (Grade D). Grade D neighborhoods were considered the least desirable or riskiest for investment. While white neighborhoods tended to fall within the green and blue grades, most of Baltimore’s Black neighborhoods, including some immigrant neighborhoods, particularly those in East and South Baltimore, were almost exclusively “redlined.” Black neighborhoods in Baltimore suffered from high rents and poor-quality housing, and limited social and city services, leading to Grade D markings. The HOLC maps showed a bias against Black Marylanders, immigrants, and blue-collar communities. Despite this, real estate brokers, mortgage lenders, and other entities consulted the HOLC maps produced for urban centers across the country. The effects led to further deterioration of many minority and working-class communities and encouraged discrimination against their residents.[7]

Despite the legal victories, race-based housing policies would continue to be present following the 1937 HOLC map. At the turn of the 20th century, migration by African Americans, Native Americans, and white people moving from the South increased Baltimore’s population. Around 175,000 new residents arrived in the 1910s and ’20s. The Great Depression and World War II exacerbated this trend. Wartime industries such as ship and airplane production provided new economic opportunities, though not equal to everyone, as Black people moving to Baltimore faced significant discrimination in employment and housing.[8]

The wartime population surge created an immediate housing and resource shortage in the city. Companies like Glenn L. Martin and Bethlehem Steel invested in temporary housing. However, they restricted the housing to white defense workers and their families. In 1941, the only available housing for Black defense workers were the Poe Home projects; however, the McCullough Homes were nearing completion. Housing for Black Marylanders was often overcrowded, and many of the buildings had deteriorated to the point of being unsafe for occupancy. Federal Public Housing Authority plans were approved to build housing for Black workers near Herring Run Park and the Brooklyn community.[9] However, mass protests by white residents caused the abandonment of these plans. Ultimately, the city developed an unoccupied tract of land in South Baltimore into the Cherry Hill neighborhood.[10] Hundreds of permanent houses were built for Black defense workers, many of which still stand today. Baltimore City’s population would reach its all-time peak shortly after the war, with 949,708 residents tabulated in the 1950 U.S. census. Despite the population boom, the city continued to hem the African American population into segregated areas, often forced to live in older structures. At the same time, white residents took advantage of newer housing developments in growing suburban areas.[11]

In the mid to late 1950s, to alleviate overcrowding in Black neighborhoods, Baltimore City built a series of high-rise, public housing developments. Although the city claimed these homes were designed for working-class residents, many Black Baltimoreans saw these developments (Lafayette Courts, Flag House Courts, the Murphy Homes, and the Perkins Homes) as a way to segregate African Americans further rather than provide homes for the working class. Initially, these new homes represented an improvement from life in dilapidated slum housing, with many projects offering community programs, swimming pools, and other activity centers. However, between 1955 and 1990, Baltimore’s high-rise developments suffered from disrepair and neglect from the city and tenants, a lack of investment, and crime. As a result, throughout the 1990s, Baltimore City began demolishing the high rises, with Lafayette Courts falling in 1995, Flag House Courts and the Murphy Homes in 1999, and Perkins Homes in 2019. The city built mixed-income housing to replace the structures in many of these communities. Nevertheless, housing discrimination still exists in Baltimore, whether by the city or by private lenders.[12]

On April 11, 1968, seven days after Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1968. Title VIII of the act, commonly referred to as the Fair Housing Act (FHA), provided “fair housing to all persons regardless of race, color, religion, sex, or nationality.” The FHA deemed activities such as refusing to rent, sell, or show homes and directing buyers to homes based on the buyers’ race, color, religion, sex, or nationality illegal. The FHA also criminalized advertisements that showed a preference to buyers or renters of a certain race or origin. Furthermore, the FHA protected homebuyers from predatory home loan lenders.[13]

Nevertheless, Black Baltimoreans still suffered from housing discrimination. In 2008, during the Great Recession, Baltimore City became the first city to use the Fair Housing Act to sue a home loan lender, Wells Fargo. The city successfully argued that the bank targeted Black neighborhoods with subprime mortgages. In 2012, a judge ordered Wells Fargo to pay a settlement of $175 million.[14]

Consistent housing discrimination and unethical practices by landlords, the City of Baltimore, and lenders limited the ability of many in the Black community to accumulate wealth. Simultaneously, they were stigmatizing neighborhoods, decreasing the number of social programs, limiting access to public works, and heightening the police presence in those areas deemed undesirable. Although the 1968 Fair Housing Act outlawed discrimination of this type, the legacy and continued unequal treatment still impacts communities today. The effects of housing discrimination in Baltimore can still be seen in the residential maps of Baltimore today. Many of the neighborhoods where people of color live today in Baltimore are the same neighborhoods into which landlords, and lenders forced Black Baltimoreans during the earlier half of the 20th century.

David Armenti is a lifelong resident of Maryland, and a graduate of Baltimore Polytechnic Institute (Poly). He currently lives in the Mt. Washington neighborhood with his wife and two young daughters. David enjoys playing and watching sports, eating ice cream, and debating current events and cultural happenings with friends.

Alexander Lothstein holds a Bachelors and Masters in History and has resided in Columbia, Maryland for almost four years. While not a native of Maryland, he has grown to appreciate the state, its history, cuisine, and, especially, flag! Outside of the museum, Alex enjoys hiking in western Maryland, taking part in reenactments of the American Revolution, and traveling around the world.

Research was drawn from a variety of primary and secondary sources, including Not In My Neighborhood, the Baltimore Afro-American newspaper archives and the Baltimore Sun archives, as well as the collections of the H. Furlong Baldwin Library.

A primary source document packet with additional resources can be accessed upon request to educationprograms@mdhistory.org.

Readers of all ages should consult Antero Pietila’s Not In My Neighborhood: How Bigotry Shaped A Great American City for a comprehensive investigation of housing discrimination and its impact in Baltimore.

Sources and further reading:

[1] Antero Pietila, Not in My Neighborhood: How Bigotry Shaped a Great American City, Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2010, pg. 15.

[2] “Baltimore Tries Drastic Plan of Race Segregation: Strange Situation Which Led the Oriole City to Adopt the Most Pronounced ‘Jim Crow’ Measure on Record.” New York Times (1857-1922), Dec 25, 1910.

[3] Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 82 (1917).

[4] “Deed and Agreement between the Roland Park Company and Edward H. Bouton Containing Restrictions, Conditions, Charges, etc. Relating to Guilford, Roland Park Company, 1913. Maryland Center for History and Culture, H. Furlong Baldwin Library, PAM 5647

[5] “Display Ad 1 — no Title.” Afro-American (1893-1988), Dec 25, 1909.

[6] Shelly v. Kramer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948).

[7] Residential Security Map of Baltimore. Found in Records of the Federal Home Loan Bank Board, 1937, U.S. National Archives, Record Group 195, Box 106. Digital Record accessed: jscholarship.library.jhu.edu/handle/1774.2/32621 .

[8] U.S. Census Bureau. Population Density, 1910 and 1920.

[9] “FPHA Approves 4 Sites Recommended by HAB in Housing of Negroes: Work Will Be Publicly Financed – Federal Agency Drops Suit for Condemnation of Moore’s Run, Philadelphia Road Location.” The Sun (1837-1987), Oct. 26, 1943.

[10] “State Official, Congressman Protest Site; 100 Urge Action: Project Won’t Remove Slums, Baldwin Says; Suggests Trailer Camp.” Afro-American (1893-1988), Jul 31, 1943. “Cherry Hill Homes to Open on May 1.” Afro-American (1893-1988), Feb 03, 1945.

[11] U.S. Census Bureau. Population Density, 1950.

[12] JoAnna Daemmrich The Sun, Staff Writer. “An End and a Beginning for Residents: Lafayette Courts Demolition Nears.” The Sun (1837-1995), Jul 27, 1995. CHARLES COHEN. “Destroying a Housing Project, to Save it.” New York Times (1923-Current File), Aug 21, 1995.

[13] “Fair Housing Act.” The United States Department of Justice, August 6, 2015, justice.gov/crt/fair-housing-act-2.

[14] Broadwater, Luke. “Wells Fargo Agrees to Pay $175M Settlement in Pricing Discrimination Suit.” Baltimoresun.com, 10 Dec. 2018, baltimoresun.com/news/bs-xpm-2012-07-12-bs-md-ci-wells-fargo-20120712-story.html.