Buttons and Badges: Rediscovering the Museum’s Political Ephemera Collection

In case you have not heard, we just held an election in the United States. Buttons, badges, hats, T-shirts, and other political ephemera are on full display in the lead up to the 2020 election. These visual, and often colorful, displays of support for particular candidates are as American as elections themselves. As early as the first presidential inauguration, supporters of George Washington wore “Long Live the President” buttons. We have been wearing political ephemera ever since.

This year, among our many exhibition openings, rebrand, and six-month closure due to the COVID-19 pandemic, we have been working on processing and re-housing this type of material to better know our collections and to make these objects accessible through our new Digital Collections Portal.

Among the more than one thousand ribbons, badges, and buttons at the Maryland Center for History and Culture, several hundred are political-related examples from the 1800s-1990s. Through this collection, we are able to show how much—and how little—political ephemera has changed over time.

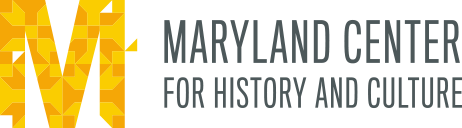

William Henry Harrison, 1840

The election of 1840, which took place between William Henry Harrison and incumbent President Martin Van Buren, is considered the “first modern election” by many political historians. It was the first election in which a candidate actively campaigned for office. The campaign was full of catchy slogans like “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too” as well as the first graphic, and widely distributed, campaign ephemera.

Campaign ribbon, 1840, silk. Maryland Center for History and Culture, 1973.11.23 b

Prior to the 1840 campaign, political ephemera typically consisted of tin or brass clothing buttons featuring the candidate’s name and their silhouette or other graphic, which could be sewn onto vests or coats. These were both practical and visual displays of support for candidates. During the Harrison campaign, large silk ribbons with both graphics and slogans were proudly pinned on coats.

Mourning ribbon, 1841, silk. Maryland Center for History and Culture, 1960.42.1

Harrison’s modern campaign strategy worked and he defeated President Van Buren by several percentage points. This success was short-lived as he contracted pneumonia at his inauguration and died after only 31 days in office. The same type of ephemera that got him elected to office was then immediately used to mourn his loss.

Zachary Taylor, 1848

Eight years after the Whig Party put President Harrison in the White House, it successfully launched the political career of General Zachary Taylor using similar tactics and ephemera. The party leaned heavily on his impressive military career and slogans or nicknames like “Old Rough and Ready.”

Campaign ribbon, 1848, silk. Maryland Center for History and Culture, 1973.11.331

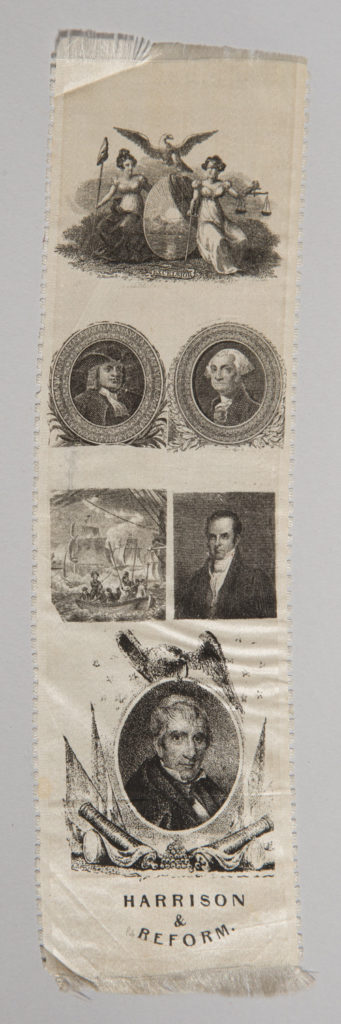

James Buchanan, 1856

In 1856, the Democratic Party rejected their incumbent, President Franklin Pierce, and propelled James Buchanan to the nomination and the White House.

Campaign Ribbon, McCoull & Slater Book and Job Printers (1856–1863), Baltimore, Maryland, 1856, silk. Maryland Center for History and Culture, 1973.11.236 a

This is both an early and rare color example of campaign ephemera. It was made by the short-lived printing firm of McCoull & Slater Plain and Fancy Book and Job Printers (1856–1863). Established at the corner of Baltimore and Sharp Streets in Baltimore, Maryland, Robert McCoull (1807–1876) and John Y. Slater (1832–1911) produced books, flags, political ribbons, and other printed materials. In 1863, the printers mutually dissolved their partnership and Slater continued the business under his own name. In 1875, the building that housed his print shop burned down, and by 1882, he declared bankruptcy.

Benjamin Harrison, 1888

By the time of President Benjamin Harrison, campaign ephemera was extremely colorful, incorporated different materials other than just silk, and even included printed photographs of the candidates. Harrison, a decorated Union officer during the Civil War, ran for president alongside Governor Levi P. Morton of New York. Together, the ticket defeated incumbent President Grover Cleveland.

Campaign badge, 1888, tin, paper, metal. Maryland Center for History and Culture, Gift of Mrs. Charles Soistman, 1959.18.4 a

“Clean Sweep” campaign badge, 1888, tin, paper, metal. Maryland Center for History and Culture, Gift of Mrs. Charles Soistman, 1959.18.4

Campaign badge, 1888, tin, paper, metal. Maryland Center for History and Culture, 1973.11.304 a

Both Cleveland and Harrison used similar-looking ephemera that incorporated whisk broom imagery for the “clean sweep” campaign slogan. This slogan was borrowed and reused by many political candidates well into the twentieth century.

Grover Cleveland, 1892

Not to be deterred by his loss in 1888, President Grover Cleveland defeated President Benjamin Harrison in the election of 1892 and became the first and only president of the United States to serve two non-consecutive terms.

Campaign ribbon, J. H. Shaw Co., Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1892, silk, fabric, metal, paper. Maryland Center for History and Culture, 1963.2.1

This type of ephemera was a combination of both new and old styles. This example still incorporates a colorful silk ribbon with fringe, but also a decorative metal pinback at the top and a printed photograph of the candidate affixed to the ribbon. This is a badge from the Democratic National Convention, which began on June 21, 1892 in Chicago, Illinois. New York, Grover Cleveland’s home state, is acknowledged beneath his portrait.

Campaign lapel button, 1892, metal, silk. Maryland Center for History and Culture, 1973.11.504 g

William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt, 1896–1905

In 1892, Benjamin S. Whitehead (1858–1940) and Chester R. Hoag (1860–1935) established Whitehead & Hoag (1892–1965) and entered the world of button making. During the 1890s, they secured three major patents, which revolutionized the industry, and political ephemera as we know it. It was during William McKinley and William Jennings Bryan’s 1896 presidential campaign that political ephemera exploded. In just that election alone, there were hundreds of different types, sizes, and styles of buttons and ribbons. This easily mass-produced and cheap advertising medium was made possible by the simple metal pinback, inserted behind a round printed piece of paper, which was encapsulated in celluloid. The Whitehead & Hoag design is still the standard of today.

Campaign badge, 1900, metal, paper, celluloid, silk. Maryland Center for History and Culture, 1963.2.14

This example features a combination of both new and old styles. A printed, celluloid encapsulated button hangs from a decorative pinback badge, which is affixed to a colorful silk ribbon. This badge was worn by members of the Reception Committee of the Union League of Maryland on November 1, 1900, during the election of 1900. New York Governor Theodore Roosevelt is featured on horseback beneath the two candidate images, which was a nod to his military success as colonel of the Rough Riders during the Spanish-American War.

Campaign button, Whitehead & Hoag Co., Newark, New Jersey, 1904, metal, paper, celluloid. Maryland Center for History and Culture, 1973.11.504 a

Campaign button, Torsch & Franz Badge Co., Baltimore, Maryland, 1904, metal, paper, celluloid. Maryland Center for History and Culture, 1973.11.614

Inauguration medal, March 4, 1905, metal. Maryland Center for History and Culture, Gift of Mr. Henry W. Duvall (1950), 1973.11.614 c

At the beginning of the twentieth century, amongst all the classic campaign buttons and colorful silk ribbons emerged all-metal pieces of ephemera like this souvenir medal purchased by an attendee of President Theodore Roosevelt’s second inauguration on March 4, 1905.

Woodrow Wilson, 1912

The Democratic National Convention was hosted in Baltimore, Maryland, at the Maryland National Guard’s 5th Regiment Armory on Howard Street. From this event came a number of different styles and designs. The party ultimately nominated Woodrow Wilson, who went on to serve two terms as president.

Convention badge, Bastian Brothers Co., Rochester, New York, 1912, metal, fabric. Maryland Center for History and Culture, 1963.2.21

Convention badge, Bastian Brothers Co., Rochester, New York, 1912, metal, fabric. Maryland Center for History and Culture, 1973.11.452

Delegate badge, Whitehead & Hoag Co., Newark, New Jersey, 1912, metal, fabric. Maryland Center for History and Culture, Gift of the Missouri Historical Society, 1980.16.1 b

Franklin D. Roosevelt, 1936–1940

Franklin D. Roosevelt served four terms as president of the United States, through both the Great Depression and World War II.

Car ornament, Wisdom Products Company, New York, 1936, metal. Maryland Center for History and Culture, 1973.11.615

During the 1920s and 1930s, the mass production of automobiles enabled many Americans to own their own vehicles. In an era before the bumper sticker, there were car ornaments like this. Roosevelt defeated Alf Landon in the election of 1936.

Campaign badge, 1940, metal, plastic, fabric, celluloid. Maryland Center for History and Culture, 1973.11.614 d

This example included not only a button and ribbon element, but a small plastic elephant, representing Wendell Wilkie’s Republican Party in the election of 1940. Roosevelt won the election for his record third term in office.

Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1952–1956

Following his success as Supreme Allied Commander during World War II, Dwight D. Eisenhower was propelled to U.S. presidency in 1952 and 1956. During both campaigns he faced off against Democratic candidate Adlai Stevenson. This interesting political badge is mostly plastic, with a pinback on the reverse, and a small blank window between “Elect” and “President.” The paper in between has the names of both candidates on it and could slide up or down to show support for either candidate.

Campaign badge, 1952 or 1956, plastic, metal, paper. Maryland Center for History and Culture, Gift of Philip Kahn, Jr., 1986.35.1

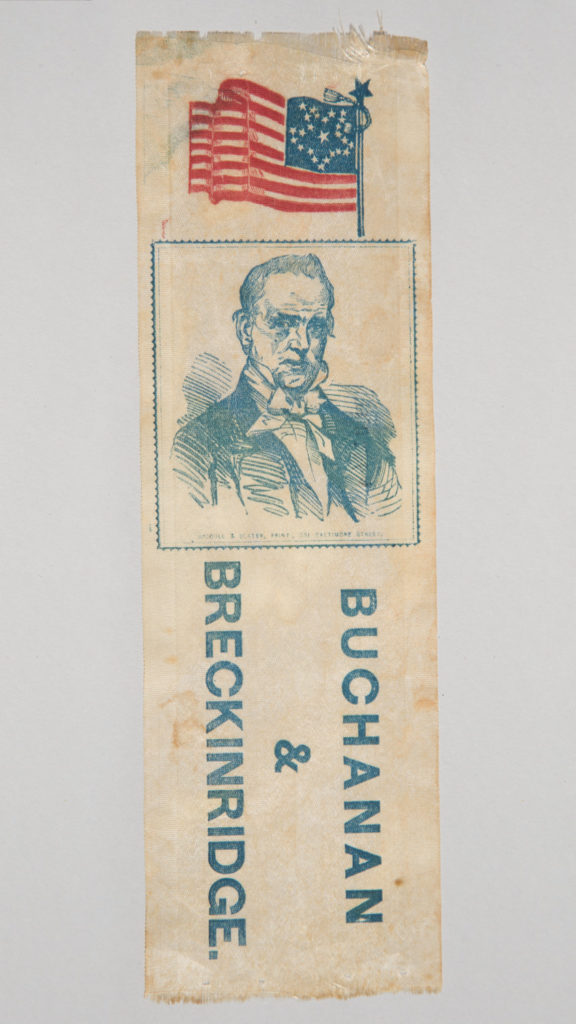

Harry Hughes, 1978–1982

Harry Hughes was a Maryland career politician. After serving in the House of Delegates and State Senate, he ran for Governor of Maryland in 1978. He was re-elected in 1982 and served until 1987. While much larger in diameter than those of McKinley’s 1896 election, and with aluminum elements, the button of the modern era continues to reflect the same style and design implemented by Whitehead & Hoag Co. and others.

Campaign button, 1978 or 1982, metal, aluminum, paper, celluloid. Maryland Center for History and Culture, Gift of Stiles Tuttle Colwill, 1988.65.1

While much has changed since President George Washington, the campaign button endures in 2020. The round pinback button with names, faces, and slogans, established in the 1890s remains a staple piece of political ephemera. To learn more about the history of Marylanders’ right to vote, please explore our first online exhibition Forgotten Fight: The Struggle for Voting Rights in Maryland.

By Harrison S. Van Waes

Associate Registrar