Conserving Transitional Fashions: The 1910s at the MdHS Fashion Archive

By Sarah Lindberg

To follow the text with a visual aid, please click on “MdHS 1910s” to download the PowerPoint.

[Slide 1]

The early 20th century was a time of dramatic change. During the 1910s, the United States became majority-urban for the first time in its history. Modernism and non-Western influences were reshaping art and architecture, and Western fashion reflects the technological and cultural changes of the era. Mass production and synthetic materials made trends more accessible, and designers were beginning to develop the modern fashion industry, which led to the differences between the fashions of 1903 (left) and 1927 (right).

[Slide 2]

To illustrate the changing silhouettes in the early 20th century, here’s a side-by-side comparison of two corsets. The one on the left is from our collection, displayed on one of our smallest dress forms, and dates to the 1900s. The one on the right, from The Metropolitan Museum of Art, dates to c. 1918. We can see that the corset on the left creates an hourglass silhouette. The corset on the right doesn’t have bust support, and instead shapes the lower torso to create a more vertical silhouette. Although all the dresses in my presentation would have been worn with corsets, those corsets would have looked very different from those worn in earlier decades.

[Slide 3]

The new silhouette reflects the changing roles of women during the 1910s. Practical suits and separates became popular as more women worked outside the home. Pants for women were also acceptable for certain situations, as this riding habit with a wrap skirt over trousers illustrates. In contrast to everyday clothing, evening dresses involved layers of lightweight fabrics and elaborate decoration. The materials used to create these dresses can make them challenging to conserve, store, and display. My presentation highlights three dresses from the 1910s with interesting conservation issues.

[Slide 4]

This evening dress originally belonged to Mary Leigh Marriott (Mrs. Eugene Martinet), who wore it during her time as a student at Western High School in Baltimore. Fuller skirts became fashionable starting around 1915, so this dress’ relatively narrow skirt dates it to the first half of the decade. The dress is lightweight silk with a sheer chiffon tunic layered over it. In contrast to the bustles and full skirts of previous decades, this dress’ tunic and narrow skirt emphasize the vertical.

[Slide 5]

The bodice is cut in one piece and sewn together under the arms, as is the chiffon tunic. With its heavy beading, silk sash accented with a large camellia, and kimono-effect collar, the tunic is an example of Orientalist styles popularized by designers like Paul Poiret and Callot Soeurs. These designers borrowed elements of East Asian and Middle Eastern design to replace the highly tailored and corseted styles of the 1900s and late 19th century. Their designs, like the tunic on this dress, are more a Western fantasy of non-Western fashion than an exact recreation of it. Tunics and layered overskirts became especially popular around 1913-14. This highly fashionable element is also responsible for most of the dress’ condition issues.

[Slide 6]

The tunic’s collar and hem are trimmed with bands of white net, embroidered with small silver-core glass beads in a scroll and leaf pattern. Glass beaded fringe trims the hem and cuffs.

[Slide 7]

The beads were originally highly reflective, producing a dramatic effect in an evening setting with gas or electric light. This closeup of a fringed cuff shows both tarnished and untarnished beads, allowing us to visualize the dress’ original appearance.

[Slide 8]

Most of the beads have since tarnished, and the oxidized silver has stained the surrounding fabric where the dress was folded for storage. In this view, the stains are where the sleeves were folded over the bodice.

[Slide 9]

Over time, the weight of the beads has stressed their lightweight chiffon and net backing. Both fabrics have torn and are starting to separate at the collar.

[Slide 10]

At the tunic hem, where the beads have the least support, their weight has pulled at the chiffon, creating runs.

[Slide 11]

Although the stress points created by the beading make the dress too fragile to display on a form, comparable dresses like this one at the Metropolitan Museum of Art allow us to envision the appearance of the Maryland Historical Society’s dress when worn. This dress shows how the fashionable styles and materials of the 1910s impact garments that survive from the decade. The next dress is an interesting example of modern materials changing with age.

[Slide 12]

This dress is part of a large donation from Georgia Fenhagen, who lived in Baltimore during the early 20th century. Evening dresses are a large part of our costume collection, since people tend to save and donate clothes that have to do with important events in their lives, and that’s more likely to be formalwear. This is a day dress, which makes it a little unusual. It also provides an excellent example of inherent vice, where a work of art’s own materials cause condition problems.

[Slide 13]

The dress’ narrow sleeves, bands of lace and embroidery, and tiered straight skirt gathered to a narrow waistband are characteristic of the early 1910s. Earlier dresses, as well as other dresses from the decade, often have strips of whalebone sewn into the bodice to mimic the structure of the underlying corset. This dress has boning at the waist, but it’s only 2-3” long, which is another example of the transitions in fashion occurring at the time. The fabrics used are white netting and sheer cotton or linen, as well as green silk piping and cord. These lightweight materials were fashionable during the decade, and they would have made the dress comfortable to wear during Baltimore’s hot, humid summers. A pair of separate net cuffs with green piping adds versatility.

[Slide 14]

The skirt has some stains and tears, but the fabric is in good condition overall. This dress’ condition issues instead come from the beaded decoration. Beads were a popular trim during the 1910s, and this dress has small white glass beads and black plastic beads decorating the bodice. The green braided belt ends in beaded tassels.

[Slide 15]

The black faceted beads used on the belt tassels are likely celluloid, an early plastic that was a common substitute for ivory and other expensive materials during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The pink and green beads are glass, and the large teardrop-shaped beads are made from another plastic like Bakelite that did not disintegrate in storage. To conclusively identify the different plastics, we would need scientific testing.

[Slide 16]

Celluloid is derived from plant fibers, while Bakelite is fully synthetic. Both types of plastic have added chemicals called plasticizers that increase their strength and malleability. Over time, the plasticizers in the black beads have migrated to the surface, producing a white crust that comes loose when touched. The loss of the plasticizers means the beads are more brittle and prone to further deterioration. Since this crust is a change to the structure of the plastic, the existing changes are irreversible. We can slow further aging of the celluloid beads by storing the dress in a stable environment. Acid-free tissue paper wrapped around the tassels acts as a barrier between the surfaces of the beads and the skirt fabric. This prevents the crust from rubbing off onto the fabric.

In Pratt House, the dress and beads were exposed to extreme annual temperature and humidity changes that stressed the materials. Acid from the original cardboard storage box may have also interacted with the celluloid and impacted its degradation. Prolonged exposure to ultraviolet light can also cause celluloid breakdown, so if the dress is ever displayed in the future, it will have to be in low lighting. Now that we have rehoused the dress using archival materials, our climate controlled textile storage will help to preserve its current condition and prevent further damage.

[Slide 17]

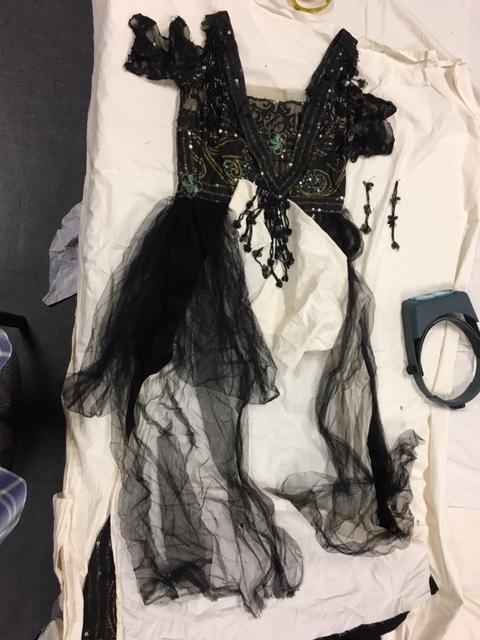

Examining this last evening dress, from 1913, was an interesting challenge.

[Slide 18]

When we first opened its box in Pratt House, this is what we saw. To examine the dress and understand its condition issues, we had to unfold it, and this turned out to be surprisingly tricky.

[Slide 19]

It looked at first like the black netting was layered over the bodice, but as we looked more closely, we realized that it was only sewn down at the waist seam. The “bodice layer” was actually a pair of free-hanging skirt panels that had snagged on the bodice sequins. So, to get a closer look at this dress, I had to use an Optivisor to detach the netting sequin by sequin.

[Slide 20]

As I worked, I slid a piece of muslin under the netting to prevent it from catching on the skirt decoration. The dress is heavy black silk, trimmed with black lace and sheer net and embellished with metal and plastic sequins.

[Slide 21]

I also uncovered this sequined train folded up inside the skirt.

[Slide 22]

The decorations on this dress have a sturdy backing fabric, unlike the first dress with its heavy beads on lightweight chiffon. In this case, the decorations themselves are showing signs of wear. Black strands of beads, accented with clusters of green paillettes, hang from the dress’ shoulders and the center of the bodice.These strands are done in standard-weight embroidery thread, and as a result several of them were loose in the original storage box. The image on the left shows the loose fringes lined up next too the dress.

[Slide 23]

The green celluloid paillettes have degraded; many of them have broken over time, and the colored coating is separating from the clear plastic backing. This has left reflective dust on the dress and its packing tissue.

[Slide 24]

Some of the sequins are broken and bent. The metal sequins have collected green particles from the plastic sequins, and we can see spots on the skirt where they stained the dress as they oxidized.

[Slide 25]

To prepare this dress for display, we would need to line the net panels to prevent contact with the skirt decoration and anchor the beaded fringes more securely. These interventions would allow us to exhibit the dress on a form while improving its stability in storage.

[Slide 26]

The Fashion Archives recently sent an evening dress from the late 1910s [double-check year] for conservation at a private lab in Alexandria. Heavy beading and embroidery had left the net overdress with numerous tears and holes, and prone to further damage. Conservators fully lined the overdress with nylon netting dyed to match. The repairs took roughly 30 hours, and left the dress ready to exhibit. The dyed netting stabilizes the dress, and the repairs are not visually distracting. Although garments from this period were not designed for long-term survival, conservators working today can preserve them.

Works Cited:

American Chemical Society. “Leo Hendrick Baekeland and the Invention of Bakelite.” Accessed July 16, 2017. https://www.acs.org/content/acs/en/education/whatischemistry/landmarks/bakelite.html.

Edwards, Lydia. How to Read a Dress: A Guide to Changing Fashion From the 16th to the 20th Century. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017.

Glasscock, Jessica. “Twentieth-Century Silhouette and Support.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000-. http://metmuseum.org/toah/hd/20sil/hd_20sil.htm. (Last modified October 2004)

Julian, Philippe. La Belle Epoque: An Essay. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1982.

Koda, Harold, and Andrew Bolton. “Paul Poiret (1879-1944).” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000-. http://metmuseum.org/toah/hd/poir/hd_poir.htm. (Last modified September 2008)

McCormick, Kristen, and Michael R. Schilling. “Animation Cels: Preserving a Portion of Cinematic History,” Conservation Perspectives: The GCI Newsletter 29:1 (2014): 10-12.

Mendes, Valerie, and Amy de la Haye. 20th Century Fashion. London: Thames & Hudson, 1999.

Milbank, Caroline Rennolds. New York Fashion: The Evolution of American Style. New York: Harry N Adams, 1996.

Olian, JoAnne. Everyday Fashions 1909-1920, As Pictured in Sears Catalogs. New York: Dover, 1995.

Preservation Of Plastic ARTefacts in museum collections (POPART). “What Plastics Are In My Collection?” Accessed July 16, 2017. http://popart-highlights.mnhn.fr/identification/what-plastics-are-in-my-collection/index.html.

Reilly, Julie A. “Celluloid Objects: Their Chemistry and Preservation.” Journal of the American Institute for Conservation 30:2 (1991): 145-162. http://cool.conservation-us.org/jaic/articles/jaic30-02-003_3.html.

Shashoua, Yvonne. “A Safe Place: Storage Strategies for Plastics,” Conservation Perspectives: The GCI Newsletter 29:1 (2014): 13-15.

Troy, Nancy J. “Poiret’s Modernism and the Logic of Fashion.” In Poiret, ed. Harold Koda and Andrew Bolton, 17-26. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2007.