Together Again: Reuniting the Silver Tureens of Judge George Washington Dobbin

By Harrison S. Van Waes, Director of Collections

Post published December 17, 2021 and Updated April 14, 2022

When an individual passes away, their possessions are often split up amongst children or other relatives. As a result, items that were once part of a pair, or larger group, are sometimes separated, never to be reunited again. Such was the case with a set of three silver tureens owned by Judge George Washington Dobbin (1809-1891).

Dobbin was born in Baltimore on July 14, 1809, to George Dobbin (1774-1811) and Catherine Bose Dobbin (1786-1875). His father, originally of Monaghan, Ireland, arrived in Maryland in 1800 and became a citizen in 1805. The elder Dobbin was an editor and proprietor of what was then called the American and Commercial Daily Advertiser as well as a law partner in Dobbin, Murphy & Bose with his brother-in-law William Bose, and a fellow Irish immigrant named Thomas Murphy.[i]

Dobbin never knew his father, but he carried on his legacy through the field of law. Following his education at Wentworth Academy, and what was then known as St. Mary’s College in Baltimore, Dobbin enrolled in the University of Maryland Law School.[ii] After graduating, he was admitted to the Bar of Baltimore on April 2, 1830 and began to practice in the city.[iii]

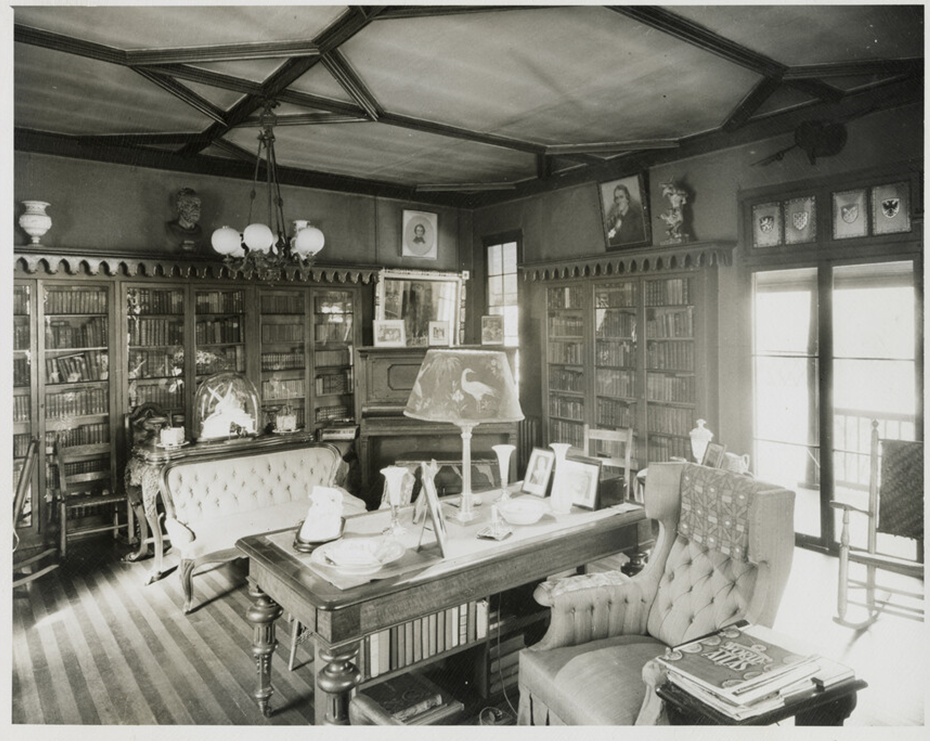

With his legal career underway, he turned to marriage, family, and other pursuits. The young lawyer married Rebecca Pue Dobbin (1812-1884) on June 27, 1831.[iv] The couple initially made their home in Baltimore and Howard Counties, and over the next fourteen years had six children, all of whom survived into adulthood, which was quite an achievement in that era. Like other affluent Baltimoreans of that period, Dobbin looked to build a summer home to escape the oppressive summer city heat. In 1840, he purchased nine wooded acres along the Patapsco River, just southwest of the Thomas Viaduct. There he built a modest cottage, which he named “The Lawn.” Shortly after the home was constructed, physicians advised him to permanently move out to the country for health reasons. As a result, the house was expanded in size and two additional buildings were added during construction periods in 1845 and 1860.[v] The Dobbin’s new home location was so popular that shortly after they moved there, several other lawyers, including John H. B. Latrobe (1803-1891), built houses nearby. The area soon became known as “Lawyer’s Hill.”[vi]

An active member of the Baltimore community throughout his life, Dobbin was a founding member of the Maryland Historical Society in 1844 (now Maryland Center for History and Culture), a trustee of Johns Hopkins University & Hospital as well as the Peabody Institute, and a Director of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad among numerous other pursuits. During the Mexican-American War (1844-1846) he served as a lieutenant colonel of cavalry in the Maryland Militia. Later, he served as a dean at the University of Maryland Law School, his alma mater.[vii]

Civil War

The outbreak of the Civil War divided many Marylanders, including the residents of “Lawyer’s Hill.” Dobbin’s friend, and fellow founder of the Maryland Center for History and Culture, John H. B. Latrobe, was a staunch advocate of the colonization of Liberia and the migration of free African Americans as an alternative to abolition. Another neighbor, Dr. James Hall (1802-1889), who moved into the home “Claremont” in 1858, purportedly had a tunnel built under his home as part of the Underground Railroad for runaway slaves.[viii] Both Latrobe and Hall served terms as president of the Maryland Colonization Society. On slavery, Dobbin was known to own one slave at “The Lawn” – Benjamin Allen Chew (1827- ) – who he freed for “diverse causes and considerations” in December 1855. He otherwise employed numerous household cooks and servants over the years.[ix]

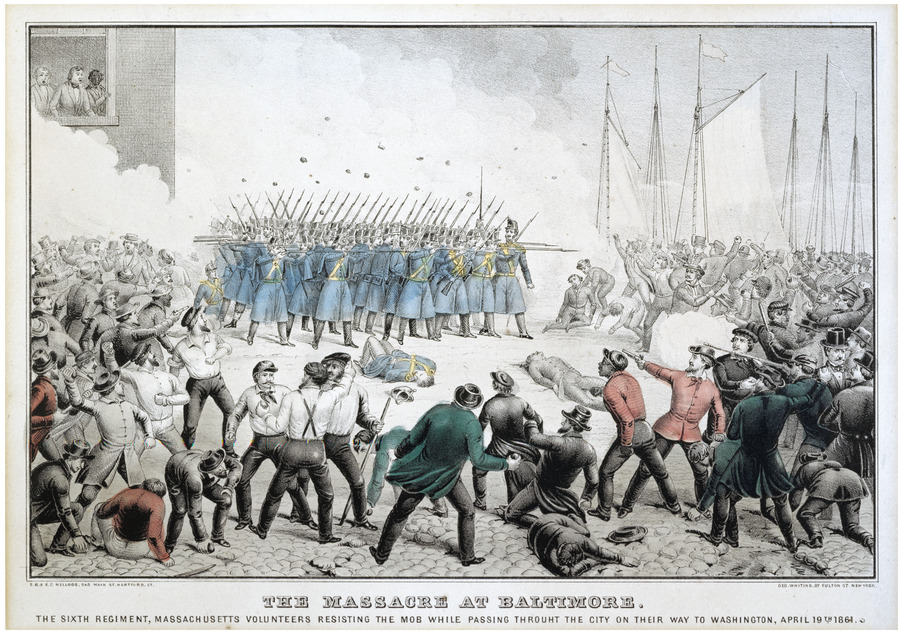

The Dobbins were known supporters of the southern cause throughout the war. In the early days following the Pratt Street Riots on April 19, 1861, Dobbin was sympathetic towards individuals caught up “in the great excitement” that led to violence or protest in and around Baltimore. Just two days later, he accompanied fellow lawyer, friend, and Mayor of Baltimore George William Brown (1812-1890) to Washington, D.C. to meet with President Abraham Lincoln so that the two leaders could discuss the atmosphere in the city and the possibilities of further troop movements in Baltimore.[x] Lincoln temporarily agreed that union troops should not pass through the city, but this was short lived as just a few weeks later the union army occupied Baltimore and held it under martial law for the rest of the war. Dobbin’s friend Mayor Brown was ultimately imprisoned at Fort McHenry for over a year due to his sympathies and actions.

A week after the riots, Dobbin was charged with prosecuting seventeen protestors who raised a rebel flag on Federal Hill and refused to take it down. After a half-hearted opening statement as the prosecution, Dobbin made “no objection to the discharge of the prisoners” and they were all freed.[xi] Shortly thereafter, he came to the legal defense of Joseph H. Spencer (1820-1889), a city merchant transporting $15,000 worth of goods to Virginia, who stopped at the army-occupied Relay House along the B&O Railroad. He verbally berated the union troops who inspected his cargo and was arrested by order of General Benjamin Butler (1818-1893).[xii] Dobbin’s daughter, Rebecca Pue Dobbin Penniman (1833-1915) later wrote bitter feelings of thieving, rude, and unsanitary troops living at “The Lawn,” which made up part of the army’s Camp Essex and union artillery positions overlooking the important Thomas Viaduct.[xiii] Like Baltimore, the Dobbin home was occupied by the union army for the duration of the war.

Post-War Years

After the war, Dobbin continued with his law practice, work at the University of Maryland, and was devoted to shaping Maryland in the post-war era. He served as a public advocate for President Andrew Johnson’s (1808-1875) Reconstruction policies, which were favorable to Democrats and former confederate states, and was made a member of Maryland’s Constitutional Convention in 1867, which included the role of chairman of the judiciary committee.[xiv] One of the provisions in the new Maryland Constitution created the Supreme Bench of Baltimore City, which oversaw five lower courts. The Superior Court was managed by five elected judges, including a Chief Judge and four associates.[xv] Dobbin ran on the Democratic ticket for one of the Associate Judge positions and beat his opponent by nearly 14,000 votes.[xvi]

Now Judge George Washington Dobbin, he took office in November 1867 with his fellow judges to begin a fifteen year term in office. In this position he commanded an excellent salary of $3,500 annually and was later awarded an LL.D by the University of Maryland. In addition to his many civic affairs, he continued his life at “The Lawn” with his family, which now included many grandchildren. In 1879, the Judge turned 70, which according to the Maryland Constitution, required his retirement from the bench. For his case, the State Legislature made an exception and he was allowed to finish out his term.[xvii]

Judge Dobbin’s Silver

In 1882, Judge Dobbin’s fifteen year term as an associate judge on Baltimore’s highest court came to an end. At the age of 72, he left office and retired from the Bar of Baltimore City after 52 years of membership. As was customary for retirement gifts of that era, the Baltimore Bar presented him with three silver tureens, made by renowned Baltimore silversmith Samuel Kirk & Son. All identical in design, two are the same size, while one is much larger. After Judge Dobbin passed away at “The Lawn” in 1891, the three pieces were split up amongst three of his four surviving children.[xviii] The largest tureen passed to his youngest daughter Mary Dorsey Dobbin Brown (1836-1895), one of the small tureens was given to his oldest daughter Rebecca Pue Dobbin Penniman (1833-1915), and the last one passed to one of his two surviving sons: Robert Archibald Dobbin, Sr. (1839-1911).

The largest tureen had the shortest route to the Maryland Center for History and Culture. Mary Brown passed it to her son Dr. George Dobbin Brown (1874-1958). In 1950, Dr. Brown donated the tureen, along with several other Brown and Dobbin family objects. It seems that knowledge of the other two Dobbin tureens was lost during or after the time of donation. In 1983, MCHC curator Jennifer Faulds Goldsborough published Silver in Maryland in conjunction with a six month exhibition of the same title. In the publication she offers this observation of the tureen:

“The maker of this heavy, handsome tureen is something of a surprise since it is almost the antithesis of the Baltimore Repousse style we associate with Kirk and Son during the 1880s. Nor is it in the so-called eclectic “Victorian” style of most American silver manufacturers of the period. It is an excellent example of how masterfully the Kirk firm could handle other styles when given the opportunity.”[xix]

Beyond these observations and other basic details, there is no information or speculation in the publication on the possibility of more than one tureen, nor is there any such information in the 1950 donor file.

In November 2020, the museum received a confusing email from a prospective donor and the great-great-great grandson of Judge Dobbin. He offered a silver tureen, identical to the one donated by Dr. Brown in 1950. The donor believed that he had the only one until he came across the catalogue entry in Silver in Maryland. After confirming that both were identical, but different in size, the donor delivered the other tureen one week later. There was great excitement on staff and within the Museum Committee of the Board of Directors regarding this acquisition. Seventy years after the donation of the first tureen, and 130 years since the tureens were split amongst Judge Dobbin’s children, the pair was reunited.

With the addition of the second tureen, Mark Letzer, President & CEO of MCHC, soon speculated that there was possibly a third tureen with this set. Through a series of communications through the MCHC Board of Directors to another Dobbin descendent, we learned that there was indeed a third example, identical to the smaller tureen, and they were interested in donating the object to the museum to complete the set. Delivered in March 2021, MCHC went from one tureen to three in just five months. After 130 years apart, and many successive generations of Dobbin-family ownership, the retirement silver of Judge George Washington Dobbin is together again, preserved at the Maryland Center for History and Culture.

[i] “Maryland Heraldry: The History of the Dobbins,” Baltimore Sun, August 19, 1906, p. 17; the newspaper later changed its name to the Baltimore News American.

[ii] St. Mary’s College was a civil school when it was established around 1805. It has been a Seminary since 1822.

[iii] American Biographical Library. Accessed at: Ancestry.com

[iv] “Maryland Heraldry: The History of the Dobbins,” Baltimore Sun, August 19, 1906, p. 17

[v] “The Lawn”, National Register of Historic Places inventory, Maryland Historical Trust https://mht.maryland.gov/secure/medusa/PDF/NR_PDFs/NR-839.pdf

[vi] Jackie Powder, “Lawyer’s Hill,” Baltimore Sun, July 21, 1991.

[vii] American Biographical Library. Accessed at: Ancestry.com

[viii] “Claremont”, National Register of Historic Places Inventory, Maryland Historical Trust. https://mht.maryland.gov/secure/medusa/PDF/Howard/HO-798.pdf

[ix] Benjamin Allen Chew’s Manumission papers are owned by the Howard County Historical Society, see Theresa Donnelly, “Freed Slaves in Howard County,” The Legacy: Newsletter of the Howard County Historical Society (2011), Vol. 48, No. 2 and Deed of Manumission, available at: Deed of manumission by George W. Dobbin for Negro slave named Benjamin Allen Chew, dated December 22, 1855 – Manumissions, Indentures, Bills of Sale – Howard County Historical Society – Digital Maryland; The 1840 census shows four free African American servants in his household. In 1850, he employed two “mulato” women and one African American male laborer. In 1860, he employed four African American servants, including a house keeper, cook, waiter, and coachman.

[x] “Statement of Mayor Brown as to his interview with Mr. Lincoln,” Baltimore Sun, April 22, 1861, p. 2.

[xi] “War Excitement in Baltimore,” Baltimore Sun, April 29, 1861, p. 1.

[xii] “The War Movements,” Baltimore Sun, May 8, 1861, p. 2.

[xiii] Elkridge Heritage Society (1983). Lawyers Hill Heritage: Elkridge – 3 Wars and the Peace.

[xiv] “To the Citizens of Baltimore,” Baltimore Sun, February 26, 1866, p. 2; “Maryland Heraldry: The History of the Dobbins,” Baltimore Sun, August 19, 1906, p. 17.

[xv] Proceedings and Debates of the 1867 Constitutional Convention, Volume 74, Volume 1, Debates 571-573.

[xvi] “Local Matters,” Baltimore Sun, October 25, 1867, p. 1.

[xvii] “George W. Dobbin”, Maryland State Archives. Accessed: https://msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc3500/sc3520/013100/013142/html/13142bio.html

[xviii] Judge Dobbin is buried at Green Mount Cemetery in Baltimore.

[xix] Jennifer Faulds Goldsborough, Silver in Maryland, p. 153