From Slave to “Self-Taught Genius”: Joshua Johnson at the Maryland Center for History and Culture

The following blog post is a reprint of an essay written by Mark B. Letzer, MCHC President & CEO, that appears in the exhibition catalog, Joshua Johnson: Portraitist of Early American Baltimore, published by the Washington County Museum of Fine Arts. [1]

Post published April 2021.

When the Maryland Center for History and Culture (MCHC, formerly the Maryland Historical Society) received a large family portrait in 1920 by Joshua Johnson (ca. 1763–1824), The James McCormick Family (1803–05), this work established a foundation for an important and nationally significant collection of American art. Long recognized as one of the first African American portraitists in the United States, Johnson created canvases of the newly emerging merchant class in Baltimore during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

The Society at that time already understood Johnson’s significance and encouraged the addition of more works by this enigmatic Maryland artist. The story of Johnson is remarkable on several fronts. The most interesting fact of his work in the early Republic was the patronage he received from his patrons living in Baltimore.

Johnson was born to a white father and an enslaved African American woman around 1763. After his manumission in 1782, he set up a painting practice and referred to himself as a “self-taught genius.” [2] More importantly, as a free black man, Johnson painted Marylanders who held enslaved individuals. These ironic circumstances are extremely complex in Johnson’s early Baltimore and warrant further study. A large population of free blacks existed in Baltimore at this time and it was interwoven with the fabric of the community. In post-Revolutionary Baltimore, there was a large population of free blacks that co-existed in this slave-holding society. David Taft Terry’s essay [in the exhibition catalogue, Joshua Johnson: Portraitist of Early American Baltimore, published by the Washington County Museum of Fine Arts] sheds some light on the social conditions related to race at that time. [3]

A doctor and scholar of local history and the fine arts of Maryland, Jacob Hall Pleasants (1873–1957) first examined Johnson in 1939 and published Joshua Johnston, the First American Negro Portrait Painter. [4] Herein he examined Johnson and reattributed portraits that had long been assigned to different artists, from Charles Willson Peale (1741 1827) and Rembrandt Peale (1778–1860) to Charles Peale Polk (1767–1822) and Jeremiah Paul, Jr. (ca. 1775–1820). Once these stylistic differences were examined and evaluated, a larger body of work and new evidence began to emerge and form the nucleus of what we recognize today as a highly significant painter and contributor to the lexicon of American art. Pleasants wrote in the foreword of the catalogue for the first exhibition of Joshua Johnson’s portraits held at the Peale Museum in 1948: “A NEBULOUS FIGURE, A Negro painter of considerable ability with a style primarily his own.” [5]

In 1987, the exhibition Joshua Johnson, Freeman and Early American Portrait Painter opened at the Maryland Historical Society in Baltimore, traveled to the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Center in Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia, then went to the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, and finally was shown at the branch of the former Whitney in Stamford, Connecticut, finalizing its tour in 1988. [6] This landmark exhibition gathered the 83 known works known to have been painted by Johnson or attributed to him and it was accompanied by a catalogue raisonné. Much has been written regarding Johnson and his reliance on, as well as his possible exposure to, the Peale family of painters. His style has been compared particularly to that of Peale Polk and this resemblance was emphasized in the seminal exhibition of 1987–88. Comparisons between his work and especially that of Peale Polk showed similarities that are certainly present in Johnson’s stylistic arrangements and could indicate such an influence. Whether Johnson was ever exposed to the Peale family of painters or Peale Polk directly we may never know, but he must at the very least have seen their works. In previous scholarship, it was still widely believed at this time that Johnson had been a protégé of the Peales.

Johnson’s painting, Mrs. John Moale (Ellin North) (ca. 1798 1800), was created very close to the time Mrs. Moale also sat for a portrait by Rembrandt Peale (ca. 1798–1800).

It is likely that Johnson would have been exposed to this work as well as other portraits in the collections of his clients. It is also significant to note that we do not know whether Johnson visited his sitters at their homes to paint them or they sat for him at his studio. In his 1798 advertisement, the artist stated that he “respectfully solicits encouragement… Apply at his House, in the Alley leading from Charles to Hanover Street , back of Sears’s Tavern.” [7] Did the clients apply and sit at his house and did it serve as his studio? As with many art historical subjects, we have few answers to the many questions regarding the set-up and the props that might have been Johnson’s.

In 1996, Jennifer Bryan and Robert Torchia published an article “The Mysterious Portraitist Joshua Johnson,” discussing the recently discovered chattel records of Johnson. [8] This was particularly insightful, especially as “one of these volumes contains the bill of sale and the manumission record of Joshua Johnson, and these prove conclusively that he was biracial, born in Baltimore around 1763. He was the son of a white man, George Johnson, and an unknown black slave owned by a William Wheeler, Sr. The documents were recorded on July 15, 1782, and concern a slave named Joshua, now aged upwards of Nineteen Years.” The bill of sale records that on October 6, 1764, Wheeler had sold the child to George Johnston or Johnson (the document spells the name both ways) for 25 pounds, then about half the price of an adult male enslaved field hand. In the manumission record, Johnson acknowledged that Joshua was his son, and arranged to free him when the young man completed his apprenticeship to Baltimore blacksmith William “Forepaw,” or when he turned twenty-one, whichever came first.” [9]

So what happened to nineteen-year-old Joshua Johnson between 1782 and 1796? He would have been free from his apprenticeship to the blacksmith by 1784. We know that the first Baltimore City Directory does not appear until 1796 so it is indeed possible that Johnson was already painting portraits prior to this directory listing but there is no way to know. What we know is that he already referred to himself as a portrait painter in this listing. We may never know how Johnson learned his trade but will continue to look for clues that led to this man’s prowess with paint and canvas.

Johnson appeared continually in the Baltimore City Directories from 1796 to 1824. He was listed as a freeman in the last two years he appeared in the Directories. His first of two advertisements appeared in the December 19, 1798, Baltimore Intelligencer as a “Portrait Painter” and, as mentioned earlier, referred to himself as a “self-taught genius.” [10]

Regarding the societal fluidity alluded to earlier, many of the sitters Johnson painted owned enslaved individuals. Was he ever concerned about losing his own freedom after regaining it? Did he ever interact with those enslaved individuals who would undoubtedly gaze upon his finished works in the houses where they served? Did the enslaved individuals in this family know who Johnson was and that he was in fact the author of these paintings? The population of free blacks and enslaved blacks in Baltimore has been studied in depth. It is telling though that by 1800, shortly after Johnson began his career in Baltimore, the ratio of freed to enslaved blacks was 2,771 to 2,843 or almost equal. In 1790, however, the ratio of free to enslaved individuals had been 323 to 1,255. This huge rise in the free black population continued to grow exponentially so that by 1820 the ratio became completely inverted at 10,326 free to 4,357 enslaved. [11] The relationship that developed among whites, free blacks and enslaved individuals continues to be mined today to better understand the origin of racial inequities in our society. However, for our purposes it opens up a possible dialogue in understanding the patronage of a former slave in an art form and profession not previously available to them. [12]

Examining the collection at MCHC, we can begin by looking closely at the two family groupings.

The James McCormick family is comprised of a mother and father flanking their three children. This protective environment of two children holding each to one parent and the other child in the center of the sofa unifies the composition. It is Johnson’s largest family grouping and was painted ca 1804. James McCormick was a merchant who emigrated from Ireland and was listed in the directories as a merchant, cabinetmaker and carpenter. [13]

The second family portrait in the collection of MCHC is Rebecca Myring Everette and Her Children (1818). Painted in 1818, it is an extraordinary composition but differs markedly from the McCormick family, not only in its more evolved style but in the way Johnson has arranged the sitter and her children. Widowed at the time of the composition, Rebecca Everette takes center stage with a daughter standing next to her and her son standing on the opposite end of the sofa. Johnson refined his style and mastered his pictorial motifs/elements: compositional formats, palette, modeling of poses and portrayal of faces, and depiction of details (lace, jewelry, brass, clothing, etc.).

As with James McCormick, Archibald Dobbin Jr. emigrated to the United States from Ireland in 1794. He was the publisher of The Telegraph, where Johnson advertised in 1802. [14] Dobbin’s fine oval spandrel portrait (1803) came into the collection in 1923. Dobbin’s portrait and that of the McCormick family were the only two Johnson portraits in the collection from the 1920s until 1976, when the Everette family portrait was donated to the institution.

For the most part, Joshua Johnson painted his neighbors. Studying the addresses of his sitters, we find an intricate network of business that lends itself nicely to being mapped out. Only two advertisements are known for Johnson. In addition to the one in 1798 in the Baltimore Intelligencer, he took out another on October 12, 1802 in the Telegraph, thanking “his friends and the public in general for their encouragement, and that he is determined to reduce his prices agreeable to the times.” [15]

Johnson must have relied almost exclusively on word-of-mouth recommendations from his friends and neighbors to continue to have patronage, especially in a city that was more and more competitive with newly arrived itinerant artists. Johnson’s sitters were mostly members of the rising merchant class. He often painted mother and daughter compositions as well as individuals of one or both sexes, and either pendant portraits or others that were meant to hang independently.

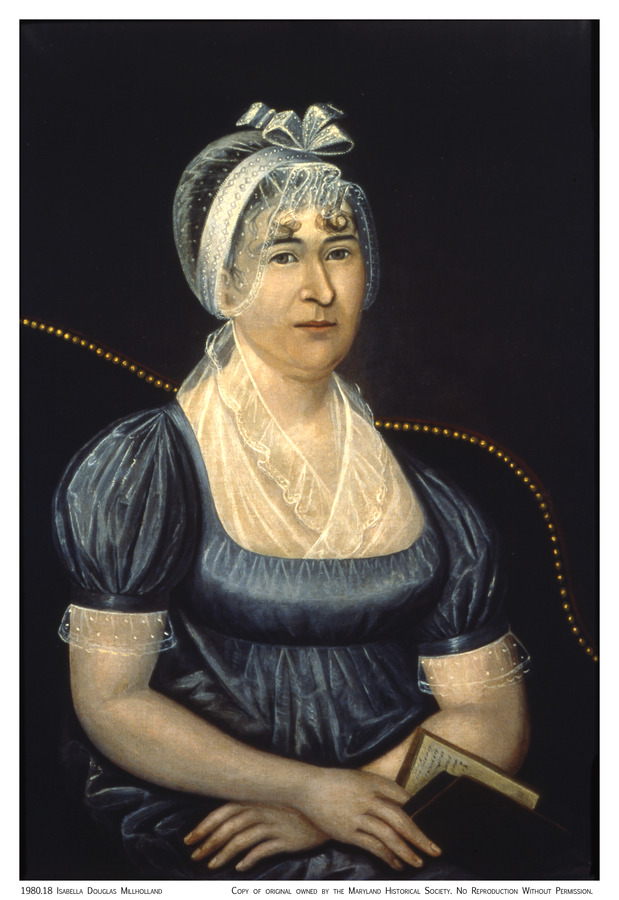

One example in the collection depicting a woman by herself is Isabella (Mrs. James) Millholland (ca. 1807). This portrait came into the collection in 1980. It depicts Mrs. Millholland sitting on a brass-studded sofa holding a book. A widow at the time this portrait was painted, she later married a Fells Point tavern keeper. [16]

Another pair of portraits, Charles Burnett (1768 –1812) and Mary Ann Jewins Burnett (1776–1838 (1812) were generously donated to MCHC in 2002. Painted about 1812, Charles Burnett is seen wearing a uniform similar to those worn in the War of 1812. It is the only known portrait by Johnson with such a uniform. Mrs. Burnett wears a diaphanous dress and mob cap showing Johnson’s renowned dexterity with the painting of lace. The Burnetts were listed as tavern owners in the Baltimore City Directory of 1800. [17]

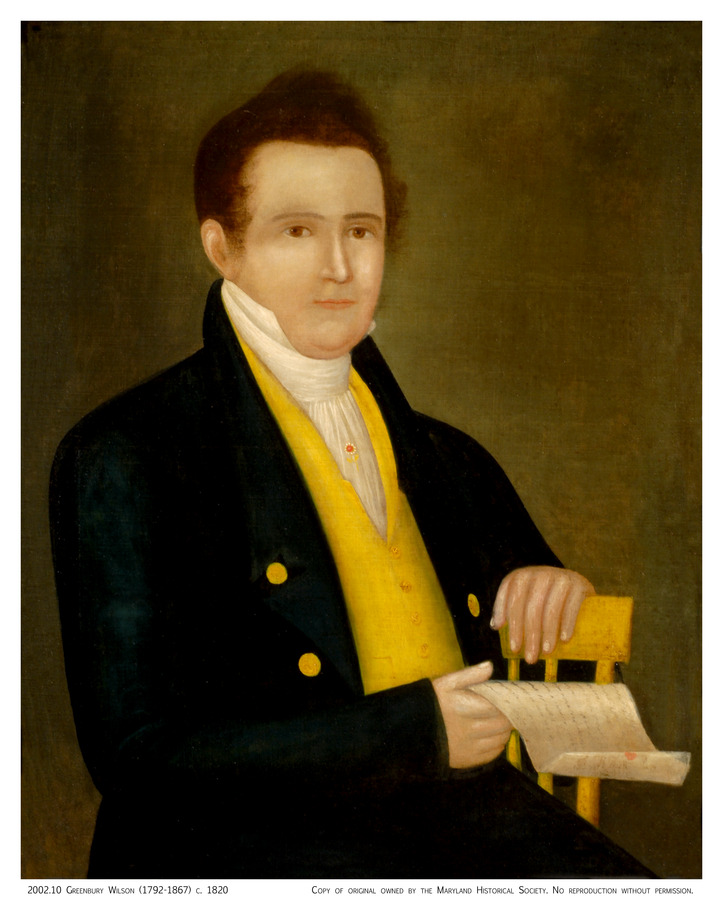

Greenbury Wilson (1792 1867) (ca. 1820) also came to the museum in 2002. Baltimore Directories indicate that Wilson was a Baltimore banker and meal seller living on Bridge Street in 1808. His business prospects changed with his marriage to Louisanna Orndorff of Washington County, Maryland, in 1826. One year after his marriage, he listed himself in the Baltimore City Directory as a flour merchant. He later became a principal shipper of that commodity to the island of Jamaica. Like the McCormicks and the Burnetts, Wilson lived in Johnson’s neighborhood.

Another fortuitous addition and the last portrait by Johnson to enter the collection (2012) is Elijah Stansbury (ca. 1821). Stansbury is depicted sitting in a chair holding a letter, with his elbow leaning on a book with a bright yellow edge. This portrait, although darker in tone so less visually interesting, features one of the most common poses used by Johnson for his sitters.

The MCHC collection is the largest grouping of Joshua Johnson portraits held in a public institution. With a total of nine paintings in our holdings, we are pleased to share this collection of portraits throughout Maryland to areas where they have not been seen or studied before, beginning in the spring of 2021 at the Washington County Museum of Fine Arts, Hagerstown. The nine works in the collection of MCHC are consistent with the rest of the sitters in Johnson’s world. All of them resided in Baltimore City near his environs of Fells Point. Two of these works are family groupings, which were his greatest artistic achievement. Only a handful of these family groups are known and MCHC is indeed fortunate to have two such paintings in its collection.

MCHC continues to collect the work of Johnson and grow its understanding of his milieu beyond the knowledge we have amassed to date. We hope stories about the sitters and their painter form connections to a larger community that will shed new light on this important period of our collective history.

Read Mark Letzer’s bio here. View Joshua Johnson portraits from the Maryland Center for History and Culture currently on loan to the Washington County Museum of Fine Arts in Hagerstown for the exhibition, Joshua Johnson: Portraitist of Early American Baltimore, on view April 17, 2021 to October 24, 2021.

Sources

- A shortened version of this essay appeared in Maryland History and Culture News (Spring 2021), pp. 22–3.

- Carolyn K. Weekley, et al. Joshua Johnson: Freeman and Early American Portrait Painter, exh. cat. (Baltimore, MD & Williamsburg, VA: The Maryland Historical Society & Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Center, 1987), p. 75.

- See in the catalogue Terry, pp. 1–18, Joshua Johnson: Portraitist of Early American Baltimore, published by the Washington County Museum of Fine Arts.

- The name appears as both Johnston and Johnson in the Baltimore City Directories. See Jacob Hall Pleasants, An Early Baltimore Negro Portrait Painter, Joshua Johnson (Windham, CT: Walpole Society 1939); idem, “Joshua Johnston: The First American Negro Portrait Painter,” Maryland Historical Magazine 37, 2 (1942): pp. 121–49; idem, An Exhibition of Portraits by Joshua Johnston, exh. cat. (Baltimore, MD: Peale Museum, 1948).

- Pleasants 1948, p. 5.

- It should be noted that this satellite location of the Whitney closed in 2001.

- Baltimore Intelligencer, December 19, 1798.

- Jennifer Bryan and Robert Torchia, “The Mysterious Portraitist Joshua Johnson,” Archives of American Art Journal 36, 2 (1996), pp. 3–5.

- Ibid., pp. 2–7.

- Weekley 1987, p. 75.

- Seth Rockman, Scraping By: Wage, Labor, Slavery, and Survival in Early Baltimore (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009), p. 27.

- In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, African Americans often worked as artisans, including

furniture/cabinet makers, carpenters, builders, sign and carriage painters, and metalworkers

or blacksmiths. - Weekley 1987, p. 123.

- Ibid., p. 115.

- Ibid., p. 80.

- Ibid., p. 136.

- Ibid., p. 150.