Juniors, Misses, Petites… Oh My!

By Molly Cohen, Fashion Archives Intern 2018

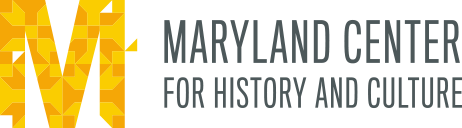

Shopping can often be a nightmare, no matter your size, shape, height, or weight. There is a severe lack of standardization in women’s clothing from store to store, and even within the same brand due to differing fashion lines.

Whose Size 8 Are You Wearing? April 24, 2011. Photo courtesy of The New York Times and sourced via all mentioned retailers.

Whose Size 8 Are You Wearing? April 24, 2011. Photo courtesy of The New York Times and sourced via all mentioned retailers.

Yet, men’s clothing, measurements, and sizing began to standardize after the Revolutionary War and continued into the Civil War. Baltimore was the leader of this movement of standardization, for it served as the epicenter of men’s fashion once it took the reigns as uniform maker for both the Union and Confederate armies.

The garment industry wanted the most efficient way to mass produce these uniforms, given the demand was continuously high during the years of war. Therefore the waist by inseam measurement we are familiar with today, which measures the wearers smallest part of the torso by the girth to hem length, emerged to standardize trousers sizes. This helped garment lofts make uniforms in as little time as possible, for they took these measurements and created a set range of increasing size options, what we may think of today as XS, S, M, L, and XL. By using the same measuring techniques, with the same size cutting techniques, and the same size chart, the garment industry was able to quickly standardize all soldier’s uniforms, and shortly after suits and workers uniforms of many trades and skills nation wide.

But what about women’s fashion? Efficiency is rarely a top priority for most designers, manufacturers, buyers, and distributors. There have always been societal factors that have contributed to the lack of mass production in women’s fashion. In comparison to men’s fashion, the differences in clothing between to elite and the rest of society were quite astounding.

Ladies Dinner Dress, unknown maker, E. Craig Importers (label), European, c.1894, silk velvet, silk brocade, silk satin, silk taffeta, jet, glass, silk floss, metal, Maryland Historical Society, Gift of Mrs. Kent Groff in memory of Mrs. A Curtis Bogert, 1978.95.63a,b.

Garments were custom made and designed for those ladies whose families could afford it; the more intricate and ornate to show their wealth, the better- as seen above. It would have taken more time to produce this type of women’s high fashion than men’s because the female body requires more measurements to be taken into consideration when constructing the garment’s silhouette. And as we have seen for centuries, women’s bodies were manipulated with different shapes of stay, corsets, crinolines, girdles, bustles, and more to control their figures and allow their custom pieces to shine in the way the designer had intended. Men’s fashion, while adopting its fair share of trends, jewels, colors, and ribbons overtime, has remained relatively the same in terms of the pieces themselves; a shirt, pants, and jacket of some sort to create a complete look.

Nine tailor’s dummies that chart changes in the preferred female silhouette from 1700 to the present, “Fashioning the Body: An Intimate History of the Silhouette” at Bard Graduate Center Gallery. July 2, 2015. Photo courtesy of Philip Greenberg for The New York Times.

Nine tailor’s dummies that chart changes in the preferred female silhouette from 1700 to the present, “Fashioning the Body: An Intimate History of the Silhouette” at Bard Graduate Center Gallery. July 2, 2015. Photo courtesy of Philip Greenberg for The New York Times.

Women’s fashion has drastically evolved during the brief history of The United States, and the forms above represent this progression, advancing left to right. The 20th century has brought upon a new set of problems in which no one is immune. With custom made clothing becoming a rarity among the common fashion shopper, finding garments that truly fit our individual and unique bodies seems like a near impossible task. The lack of standardization in sizes is a large contributing factor to this, but what is in the way of us getting to that point now? Universal language of fashion sizes.

The concept of “the juniors section” is thought of today as a place for most women with any semblance of style to avoid. Filled with piles of graphic tees, bedazzled jeans, emoji hoodies, and hot pink sweatsuits, juniors has clearly always been the one stop shop for the modern preteen, right? Wrong. The juniors section first came into play in the early 1950’s and was an area grown women could shop if their proportions were smaller than most adults their age. Junior is described as “shorter waist, high bust, lean diaphragm, average arms and hips, varies in height, has a young firm figure” (Dress measurements in a diagram of special sizes, 1952, p. 21). The dress trade 6 classified the junior as a “size, not an age” (Mestres 5). Quoted in Women Wear Daily, “junior-miss garments were made for a woman who is high-busted, slender-waisted and a slight touch shorter from shoulder to waist (usually 15″ – 15 1/2″)” (Plautz).

Arnold Junior Miss fashions in Merrimack Velveteen, 1952. Photo courtsey of The Nifty Fifties.

Arnold Junior Miss fashions in Merrimack Velveteen, 1952. Photo courtsey of The Nifty Fifties.

Tippi Hedren wearing an Arnold Junior-Miss dress in Merrimack Velveteen, 1950. Photo courtesy of The Nifty Fifties.

Tippi Hedren wearing an Arnold Junior-Miss dress in Merrimack Velveteen, 1950. Photo courtesy of The Nifty Fifties.

The Junior-Miss combo title, as seen in the ads above, was adopted to specify that the junior element was modifying the Miss clothing, keeping it within the women’s fashion world, as opposed to a form of children’s wear that we consider junior clothing to be today. Women with these afore mentioned smaller proportions who would have worn Junior- Miss apparel now have to turn to the petite section in stores to find properly fitting clothing. Yet the petite line has a convoluted history as well, making it hard for modern shoppers to pinpoint where they need to shop for their bodies:

“In 1958, the Department of Commerce released updated body measurements for patterns and apparel for women. There were three separate junior size charts: regular, petite, and tall…The number of measurements listed for each size classification was far more than previous charts which mainly included bust, wait and hip. This allowed more detailed information for patterns makers; however, it created more work for them due to the addition of sub-classifications within junior apparel.” (Mestres 12).

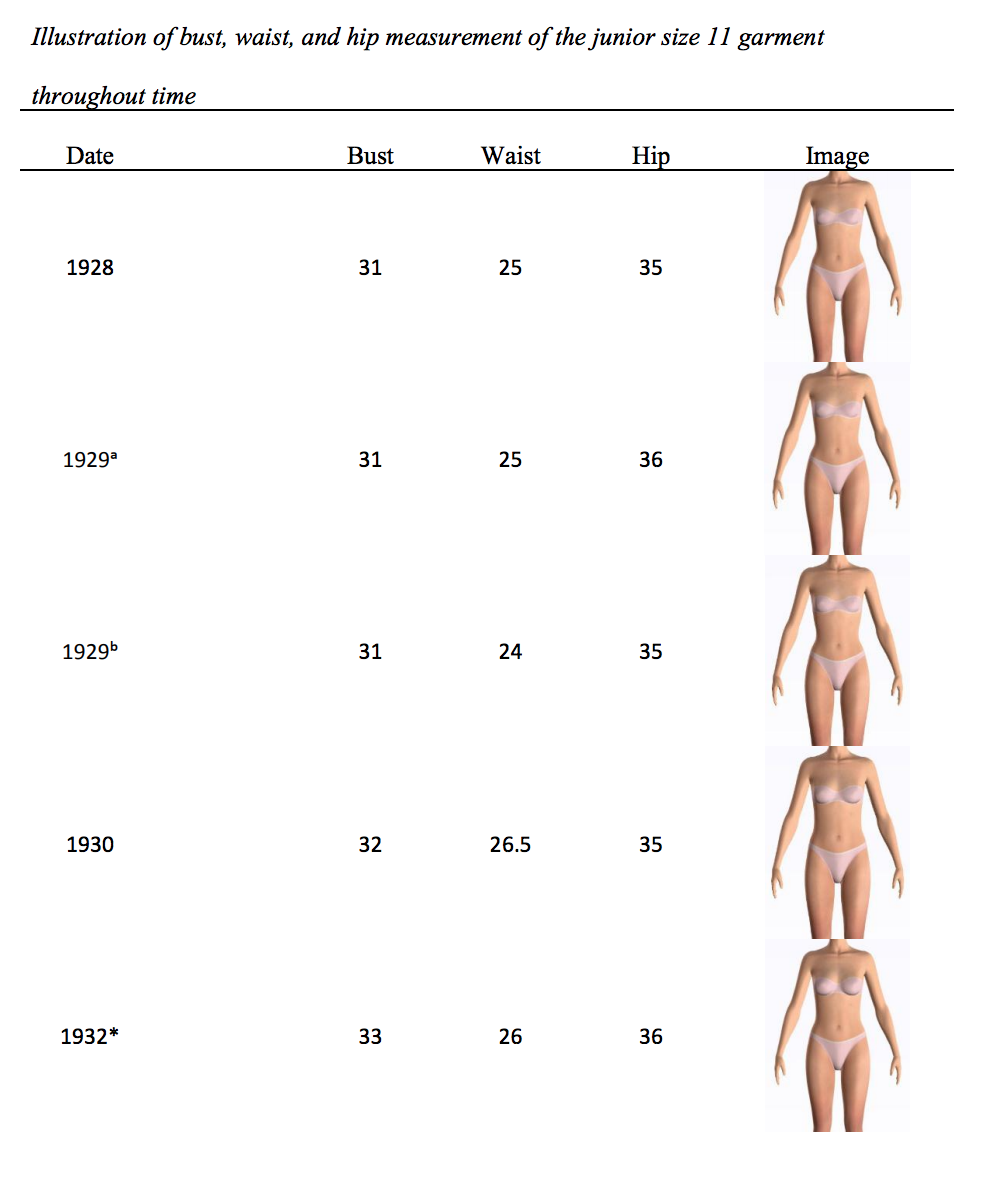

Illustration of bust, waist, and hip measurement of the junior size 11 garment throughout time. Table courtesy of THE JUNIOR APPAREL CONSUMER: An ethnographic and case study approach examining the current junior wear client, By Jaime Lynn Mestres, May 2012.

Illustration of bust, waist, and hip measurement of the junior size 11 garment throughout time. Table courtesy of THE JUNIOR APPAREL CONSUMER: An ethnographic and case study approach examining the current junior wear client, By Jaime Lynn Mestres, May 2012.

Petites has been conflated with junior’s and women’s as a subcategory for years. Not until the 1980’s did it begin to replace the junior’s section, for before it was only considered a height definer; regular, petite, or tall. This lack of universal language among fashion buyers, sellers, and lines causes increased anxiety for those who do not fit into standard sizes, which most of us truly do not. For years The Department of Commerce regulated ideological sizing, as shown above. But, as companies began expanding internationally and online, it became hard to control the products being released, and the intense speed, turn over, and progression that companies did and still do so. As shoppers, we must have agency over the products available to us and to demand that a standardization be adopted in women’s fashion as it is in mens.

New Call-to-action

References:

Mestres, Jamie Lynn. THE JUNIOR APPAREL CONSUMER: An Ethnographic and Case Study Approach Examining the Current Junior Wear Client . A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri, May 2012.

Plautz, Mary. “What’s in a Size? 1950s Junior Sizes.” Couture Allure Vintage Fashion, May 2011, coutureallure.blogspot.com/2011/05/whats-in-size-1950s-junior-sizes.html.