Lottie Barton: Dressmaker, Importer, Smuggler

Nora Ellen Carleson, Summer 2018 Fashion Archives Intern

To this date, little research has been completed on late-19th and early-20th century Baltimore dressmakers. Of course, there has been significant study on the many prominent department stores in the city, such as Hutzler’s, The Hecht Company, and Stewart & Co. However, from the 1870s to the 1920s, Baltimore hosted a thriving culture of dressmakers and importers beyond the world of the luxury department store.[1] There is no doubt that among the many dressmakers of superb quality in the city, such as Fuechsl, Chaney, O’Connor, and Madame Jeannert, the name Lottie Barton stands out as the one of the most prominent makers in the region. Formally Charlotte Mary Barton, but known professionally as Lottie, her name stands out not only for her connections to First Lady Frances Cleveland and her spectacular creations of the late 19th- and early 20th-centuries, but also for her smuggling of fine Parisian goods, which made her famous, even if only for a day, across the entirety of the United States in 1893.[2]

Wedding dress (label detail), Lottie Barton, Baltimore, MD, 1889, Maryland Historical Society, 45.45.1a-b, Gift of Mrs. C. Stewart.

Lottie Barton first appears in the Baltimore city directories as a dressmaker in 1883, though we know from census materials that she was listed as a dressmaker around 1880.[3] At that time her establishment was located at 206 N. Howard St.[4] Like other dressmakers of her day, she changed location every few years–either because of success and expansion, difficulty making rent, or changing neighborhood dynamics. It appears that even during her early years of business, Ms. Barton made gowns in step with the high style fashions of the day. While today she is best known as a dressmaker to First Lady Frances Cleveland, other elite Marylanders sought her garments as prized pieces, some of which reside in the Fashion Archives here at the MdHS.[5]

Wedding dress (bodice detail), Lottie Barton, Baltimore, MD, 1889, Maryland Historical Society, 45.45.1a-b, Gift of Mrs. C. Stewart.

One of the earliest dresses from Barton of Baltimore at the MdHS is a wedding dress worn by Elizabeth O’Donovann when she married C. Stewart Lee on January 25, 1889 in the Baltimore Cathedral (45.45.1a-b). The gown is made of a thick, lined, cream silk satin, which would have kept the bride warm during her winter wedding. The silk and the silhouette with its high collar, long puffed sleeves, and narrow waist provide a canvas that displays a delicately beaded pattern of bell flowers and curling branches constructed of incredibly small seed pearls. The motif echoes the trend of swirling interlaced floral motifs seen on other decorative arts of the day. Here one can see Barton’s work follows the popular designs of the period.

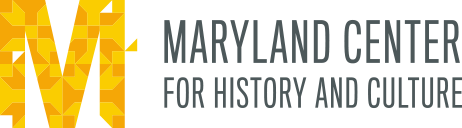

The skirt on this dress was so large that we needed an extra large box for safe storage Here you see it spread out getting ready to be packed away. Wedding dress (skirt), Lottie Barton, Baltimore, MD, 1889, Maryland Historical Society, 45.45.1a-b, Gift of Mrs. C. Stewart.

Throughout the 1880’s and 1890’s Lottie Barton appears to have been quite successful, dressing first ladies Frances Cleveland and Caroline Harrison and expanding her business to 405 N. Charles Street in Baltimore and 1415 H St. NW in Washington, D.C. In 1894, the Baltimore Sun reported on Lottie’s expansion and refurbishment of her atelier at 405 N. Charles Street. The paper wrote in detail the layout of the shop, which included a tailor’s shop in the basement, reception, fitting, and showrooms on the first floor, her private compartments on the second floor, and workrooms for her seventy five employees on the third and fourth floors.[6] The paper described the décor as incorporating “harmonious shades of green in carpet, walls and furniture, with ivory and gold woodwork in the front rooms and polished oak wood work and fittings in the back rooms.”[7] To be given such an account in the newspapers speaks to the establishment’s importance in the city.

Image of 405 N. Charles St. today, once the atelier and home of Lottie Barton. Photograph by Nora Ellen Carleson.

Image of 405 N. Charles St. today, once the atelier and home of Lottie Barton. Photograph by Nora Ellen Carleson.

Continuing to allude to her prominence not only as a dressmaker, but also as a member of the city’s community, the Baltimore Sun records Lottie’s travels to Europe multiple times a year throughout her career, during which she bought goods, saw the latest styles, and once even had private meeting with the Pope.[8] However, her name and success seemed to be known only in the Baltimore and Washington, D.C. areas until 1893 when she made national news when apprehended and charged as a smuggler in New York City.[9]

On March 16, 1893, the New York Sun first reported that Lottie Barton of Baltimore, along with two other dressmakers from Chicago, had been apprehended by customs officials in New York City. The three women were traveling back from Europe when they were charged with smuggling goods into the country, valued at $5,000 for sale, by declaring them as personal goods. Lottie had in her possession two trunks full of fine dresses, fabrics, and accessories, including over forty pairs of kid leather gloves, parasols, a gown by Worth of Paris, under garments, and yards of lace and fabric among other items. The other women, including Lottie’s friend and traveling companion, Catharine Holland of Chicago, were reported as pleading with officials that the goods were their own and crying hysterically during their questioning, all while Lottie remained stoically calm.[10] From these accounts of the women’s detainment, which became national news and appeared in newspapers across the country for the next few days, one gets a brief glance into not only Lottie’s sometimes questionable business practices, but her personality as well.[11]

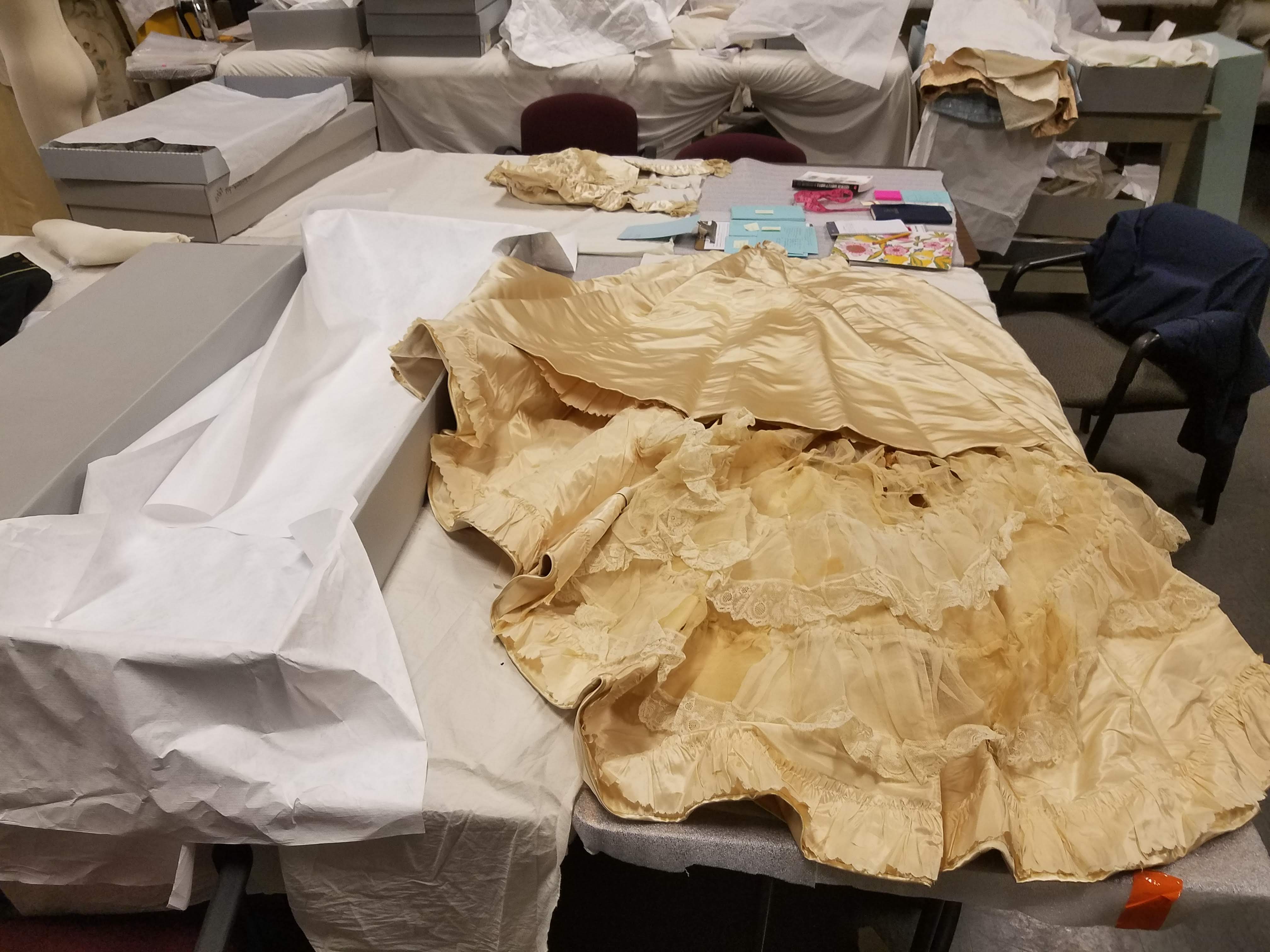

Reception / Dinner Dress, Lottie Barton, Baltimore, MD, c.1900, Maryland Historical Society, 69.122.7a-b, Gift of Mrs. Richard C. Riggs.

Reception / Dinner Dress, Lottie Barton, Baltimore, MD, c.1900, Maryland Historical Society, 69.122.7a-b, Gift of Mrs. Richard C. Riggs.

The detainment appears to have had little to no effect on Lottie’s career or business as smuggling of European goods and the copying of foreign styles was standard practice by American dressmakers of the period. She clearly continued to dress fashionable high society women in and around Baltimore and Washington, D. C. One example of this is another ensemble in the MdHS collection with a Barton label. Made closer to the end of her career, this piece consists of a bodice and skirt in a striking combination of red and black silk (69.122.7a-b). The sleeves of the bodice and skirt are comprised of a thickly woven black watered silk, also known as a silk moiré. While the majority of the bodice is made of a cherry red silk satin, it is covered with a black lace netting and adorned with rows of jet beads. Donated in 1969 as a gift of Mrs. Richard C. Riggs, the piece was originally worn by Mary Anna Jenkins Cromwell Riggs (1865-1937), the wife of former MdHS President, Clinton Levering Riggs.

Reception / Dinner Dress (Bodice), Lottie Barton, Baltimore, MD, c.1900, Maryland Historical Society, 69.122.7a-b, Gift of Mrs. Richard C. Riggs.

This piece was discovered to be a Barton ensemble when it was noticed that the Petersham Band, a waistband sewn into the interior of a bodice, had been altered at some point in the outfit’s history and, when reattached, was sewn on backwards. This had, until this summer, hidden the Barton of Baltimore label.

Reception / Dinner Dress (interior label, bodice), Lottie Barton, Baltimore, MD, c.1900, Maryland Historical Society, 69.122.7a-b, Gift of Mrs. Richard C. Riggs.

Not long after the creation of this gown, Lottie Barton of Baltimore passed away at the end of July in 1902 after fighting a long-term illness.[12] Noting her death, the Baltimore Sun labeled Lottie as “the minister of aesthetics in the mysterious realm of womanly costume.”[13] In addition to mentioning Lottie’s skills as a dressmaker, the paper continued to memorialize her by stating that “Miss Barton’s popularity was not based alone on her talent in her profession and her position as a creator of beauty in dress and an arbiter in the matter of elegance and good taste, but on amiable, personal qualities as well, which endeared her to a very large constituency.”[14]

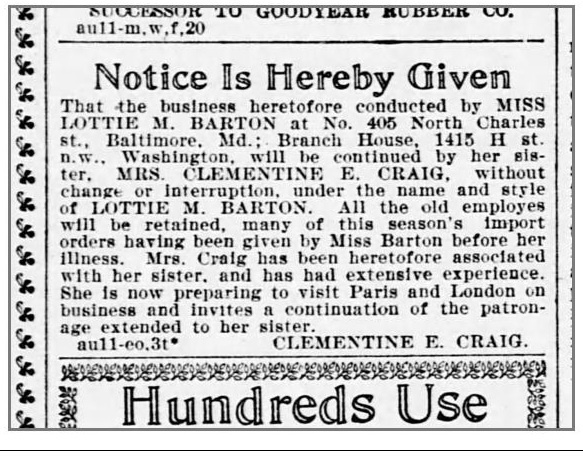

“Notice is Hereby Given,” Evening Star (Washington, DC), August 11, 1902, 5

It appears that after Lottie Barton’s death, her sister, Clementine E. Craig, an importer and possibly a dressmaker, took over her business.[15] Mrs. Craig is also known to the MdHS Fashion Archives as the importer of the 1894 Art Nouveau-style dinner dress housed in the collection. Soon after Mrs. Craig’s tenure as the owner of the establishment, the story of Lottie’s atelier is lost. Yet, through further research and the discovery of more works by Barton of Baltimore, the history of this single business woman who played a pivotal role in shaping the styles of American women will hopefully emerge.

Read More :

1) “Finding First Lady Frances at the MdHS Fashion Archives” –http://blog.mdhs.org/costumes/finding-first-lady-frances-at-the-mdhs-fashion-archives)

2) “Art Nouveau Fashion: Giving Dress a Place Among Decorative Arts” – http://blog.mdhs.org/costumes/art-nouveau-fashion-giving-dress-a-place-among-decorative-arts

Sources:

[1] Jacque Kelly,“Revisiting the heyday of department stores and five-and-dimes,” Baltimore Sun (Baltimore, MD), October 26, 2016

[2] “Tearful Smugglers Plead.” The Sun (New York, NY), March 16, 1893, 1.

[3] Woods’ Baltimore city directory (Baltimore, MD: John M. Wood, 1883), 1159; Ancestry.com, Provo, UT, 1980 United States Federal Census, Baltimore, Baltimore (Independent City), Maryland; Roll: 499; Page: 132B; Enumeration District: 048, “Charlotte Barton,” accessed August 15, 2018.

[4] Woods’ Baltimore city directory (Baltimore, MD: John M. Wood, 1883), 1159

[5] “Frances Folsom Cleveland’s White House Wardrobe,” WHHA, accessed July 10, 2018, https://www.whitehousehistory.org/frances-folsom-clevelands-white-house-wardrobe; Nora Ellen Carleson, “Finding First Lady Frances at the MdHS Fashion Archives,” The Fashion Archives Blog, last modified August 2018, accessed August 15, 2018, http://blog.mdhs.org/costumes/finding-first-lady-frances-at-the-mdhs-fashion-archives.

[6] “Improvement on North Charles Street,” Baltimore Sun (Baltimore, MD), May 29, 1894, In and About Town, Almanac for Baltimore This Day, 8.

[7] Ibid.

[8] “Personal” Baltimore Sun (Baltimore, MD), March 8, 1897, 10; “City News.” Baltimore Sun (Baltimore, MD), August 26, 1890, 4; “Personal.” (Baltimore, MD), February 8, 1900, 10.

[9] “Tearful Smugglers Plead.” The Sun (New York, NY), March 16, 1893, 1; The Philadelphia Inquirer, (Philadelphia, PA), March 17, 1893, 5; “Seized Chicago Costumes.” The Morning Democrat (Des Moines, IA), March 17, 1893, 1; “The Seized Trunks.” Baltimore Sun (Baltimore, MD), March 17, 1893.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid

[12] “Notice is Hereby Given,” Evening Star (Washington, DC), August 11, 1902, 5.; “Death of Useful Citizens,” Baltimore Sun (Baltimore, MD), July 31, 1902, 4.

[13] “Death of Useful Citizens,” Baltimore Sun (Baltimore, MD), July 31, 1902, 4.

[14] Ibid.

[15] “Notice is Hereby Given,” Evening Star (Washington, DC), August 11, 1902, 5.

New Call-to-action