Scattered across the Globe and the Political Spectrum: The Tilghman Family in the Revolutionary War

Tench Tilghman can be seen with George Washington in this Charles Willson Peale painting. George Washington and his generals at Yorktown. Oil on canvas by Charles Willson Peale, ca. 1781. 1845.3.1. Maryland Historical Society.

On March 16, 1777, twenty-seven year old Anna Maria Tilghman wrote to her father, James, “I was made happy by the appearance of a Letter from my Brother Tench but when I came to open it it almost broke my heart. He talks of never seeing us again and says if he should fall it will be in such a way and in such a Cause that we shall never blush when we hear his name mentioned. . . . I shall ever regret his differing in sentiment from you on such an important occasion as the present dispute but as I do not understand the subject I shall conclude.”[1]

Who was Tench, her oldest brother? On what subject did her father and brother disagree? And for what cause was Tench willing to fall? Tench Tilghman was General George Washington’s longest serving aide, by his side for seven years. Tench’s father, James, was a loyalist who was arrested (and paroled) in 1777 while residing in Pennsylvania, where he had moved from Maryland in the early 1760s. That arrest had a remarkable ripple effect. James’s fourth of six sons, Philemon, ran away at the age of 16 to the British Royal Navy. James wrote to a friend on October 31, 1777, “He [Philemon] writes me he took the Step in resentment for the Injuries offered me by the Penna Government as it was then thought I should be removed from thence & not allowed to come to Maryland, And that no other motive should have prevailed on him to take Arms against a Country he can no longer call his own.”[2] Despite attempts from family members to get him back home, Philemon remained in the Royal Navy.

Philemon survived the HMS Somerset wrecking along Cape Cod, Massachusetts, in November 1778 (which destroyed the ship and killed twenty-one), and continued his service off the coast of England. He later eloped with Harriet Milbanke, a daughter of British Admiral Mark Milbanke. Philemon and Harriet moved to Maryland in 1788. Not quite ten years later, in 1797, Philemon died at the age of 36, leaving Harriet with four daughters and a son, ages 10 and under. Harriet decided to return to England, even though, as she wrote in June 1797 to Philemon’s brother William, she had “the fear of a Cold reception” from her parents.[3] Her fear was not unfounded: her father did not acknowledge her return, did not see her for several months, and did not see her children for a few more months. Harriet’s regular letters to William reveal the frustration and hurt she felt from her own family division, while grieving the loss of her husband. She wrote to William in 1797, in reference to trying to do the best for her children, “My Affections hover round the Grave of their Belov’d their regretted Father.”[4] Perhaps her own father’s distance was because she had not just eloped, but eloped with a colonist.

The second oldest Tilghman brother, Richard, joined the East India Company and ultimately worked as an attorney in Bengal, India. In a June 10, 1776, letter to a friend, James wrote of Richard, “Induced by the wretched prospect of affairs here and of better in the East Indies he is on his way thither.”[5] Richard desired to avoid getting caught up in the political divisions leading to war.

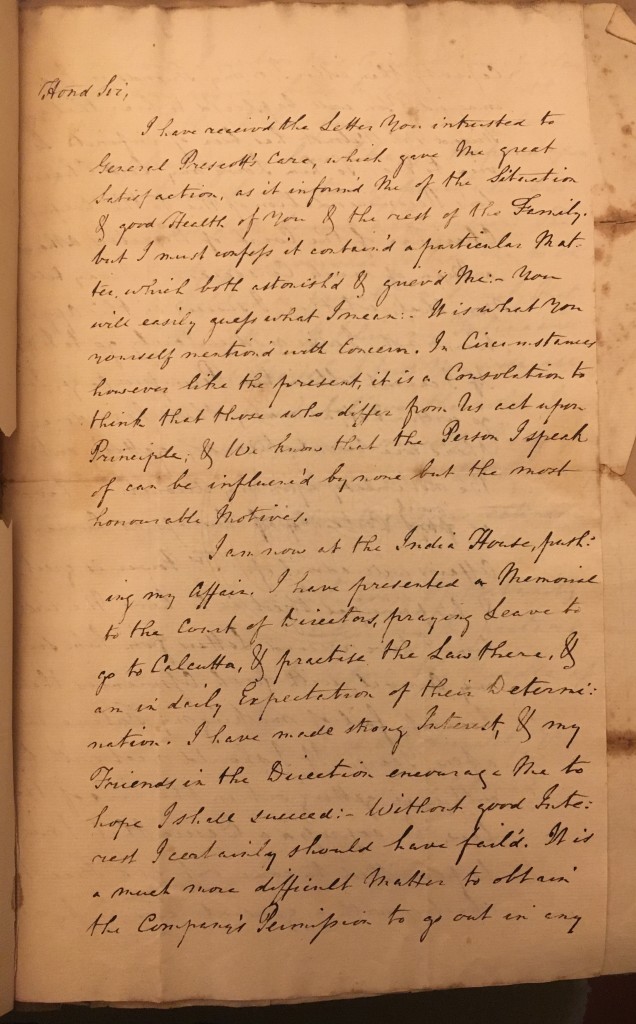

The first paragraph of a letter from Richard to his father on December 11, 1776, appears to include a reaction to Tench’s decision to serve with Washington: “I must confess it [a recently received letter] contain’d a particular Matter, which both astonish’d & griev’d Me:- You will easily guess what I mean:- It is what you yourself mention’d with Concern. In Circumstances however like the present, it is a Consolation to think that those who differ from Us act upon Principle; & We know that the Person I speak of can be influenc’d by none but the most honourable Motives.”[6] The timing of the letter provides strong evidence that his shock was at Tench’s action. Richard noted later in the letter he was reluctant to say too much on politics or family, which could explain his not naming Tench at the beginning of the letter.

Letter from Richard Tilghman to James Tilghman discussing Tench’s choice to the patriot cause. Richard Tilghman to James Tilghman, December 11, 1776, Tilghman Family Papers, MS 2821, Box H, Letterbook p. 42, MdHS. (REFERENCE)

Loyalist James, who had sons scattered across the globe and the political spectrum, had his own brotherly disagreement. His youngest brother, Matthew, is considered the “Father of the Revolution” in Maryland. James wrote to a friend on October 2, 1774, regarding a meeting of “deputies” from the colonies that had been going on in Philadelphia for almost a month. The meeting was the First Continental Congress. James wrote, “One of my Brothers [Matthew], the Speaker of the Maryland Assembly, is of this Congress and lodges with me, And yet I know nothing of what’s going. He can neither divulge, nor I inquire, consistent with the principles of Honor . . . he is a man of steadiness and Moderation, and of the strictest Virtue, and utterly averse from all violent Measures.”[7] Matthew and James maintained a strong relationship during the war, staying in touch by letter when they were apart. Their letters show a mutual respect, trust, and care for one another and their families.

Various members of the Tilghman family wrote faithfully to each other during the Revolutionary War, even though they did not agree on politics. There are no indications of permanent discord, and not even any temporary discord beyond immediate reactions to disagreeable news. Sadly, any post-war joys did not last long. Both Tench and Richard died in 1786 from diseases picked up during their respective occupational choices for the Revolutionary War—military service and employment in India. Their father took the losses equally hard. He wrote to Philemon on September 10, 1786, that the news of Richard’s death was “like daggers to my heart[.] I had not recovered from the loss of poor Tench when I am again wounded in a part equally tender.”[8] He had been proud of his two oldest sons, no matter what their political choices. (Jessica J. Sheets)

Jessica J. Sheets was a Lord Baltimore Fellowship recipient. She is currently a doctoral candidate at Penn State Harrisburg and Research Historian at the U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center.

[1] Anna Maria Tilghman to James Tilghman, March 16, 1777, Tilghman Family Papers, MS 2821, Box E, Letterbook p. 51, Maryland Historical Society (MdHS), Baltimore.

[2] James Tilghman to B. Chew, October 31, 1777, Tilghman Family Papers, MS 2821, Box K, Letterbook p. 7, MdHS.

[3] Harriet Tilghman to William Tilghman, June 1797, Tilghman Family Papers, MS 2821, Box 12, Folder 7, MdHS.

[4] Harriet Tilghman to William Tilghman, October 24, 1797, Tilghman Family Papers, MS 2821, Box 12, Folder 7, MdHS. National Park Service, “HMS Somerset (III),” https://www.nps.gov/caco/learn/historyculture/somerset.htm.

[5] James Tilghman to William Baker, June 10, 1776, Tilghman Family Papers, MS 2821, Box D, Letterbook n.p., MdHS.

[6] Richard Tilghman to James Tilghman, December 11, 1776, Tilghman Family Papers, MS 2821, Box H, Letterbook p. 42, MdHS.

[7] L. G. Shreve, Tench Tilghman: The Life and Times of Washington’s Aide-de-Camp (Centreville, Md.: Tidewater Publishers, 1982), 207.

[8] James Tilghman to Philemon Tilghman, September 10, 1786, Tilghman Family Papers, MS 2821, Box K, Letterbook p. 35, MdHS.