Spinning the Fabric of a Nation: A Nineteenth-Century Spinning Wheel and Early Linen Production in Maryland

From getting dressed in the morning to curling up under a cozy blanket, we interact with fabrics every day. But how well do we really understand how those fabrics were made or their individual histories? While this flax spinning wheel from the Maryland Center for History and Culture’s collection may appear unassuming, it actually spins a tale of American history.

Figure 1: Spinning wheel, 1840–1860, Maryland Center for History and Culture, Gift of Mary Claggett on behalf of David Clark Claggett, 2019.3.1

Now listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the Cottage plantation home is presently recognized for its Greek Revival style and for the notable Marylanders who lived there, including the politician Charles Claggett (1819–1894). [1] However, there were more Marylanders who lived there whose names have since been lost to history, and their stories deserve to be told as well. Located near Upper Marlboro in Prince George’s County, Maryland, the Cottage was historically home not only to the Claggett family, but also to those they enslaved there. It was also home to this spinning wheel, which was used by those enslaved laborers.

Linen was an often-imported fabric from the very founding of the colonies in the seventeenth century. Rather than pay exorbitant tariffs and fees to import fine European linen, many American families undertook the production of the fabric themselves as an act of patriotism and resistance to British rule. [2] However, because the process of refining flax fibers into linen was so labor-intensive, and because of the abundance of cotton in the United States, American flax production never became a profitable industry, instead remaining a domestic endeavor. [3] However, the wealthiest families would of course not perform that labor themselves, but would instead have their enslaved workers complete this arduous task.

This spinning wheel was specifically made to spin flax fibers into linen string, which was a much more difficult process than spinning wool or cotton. The delicate nature of the flax fiber required innovations in the spinning wheel, a technology that had been around for centuries, including a foot brake and a distaff spindle to keep the long, unspun fibers from becoming entangled. [4] Our records indicate that this spinning wheel was employed in making “linsey-woolsey” fabric. This whimsically named hybrid fabric is comprised of a linen warp thread and a wool weft, thus making efficient use of two fibers that were difficult to produce domestically in America. [5] The final product offered a softer and warmer alternative to the buckrams and tows that were typically made here.

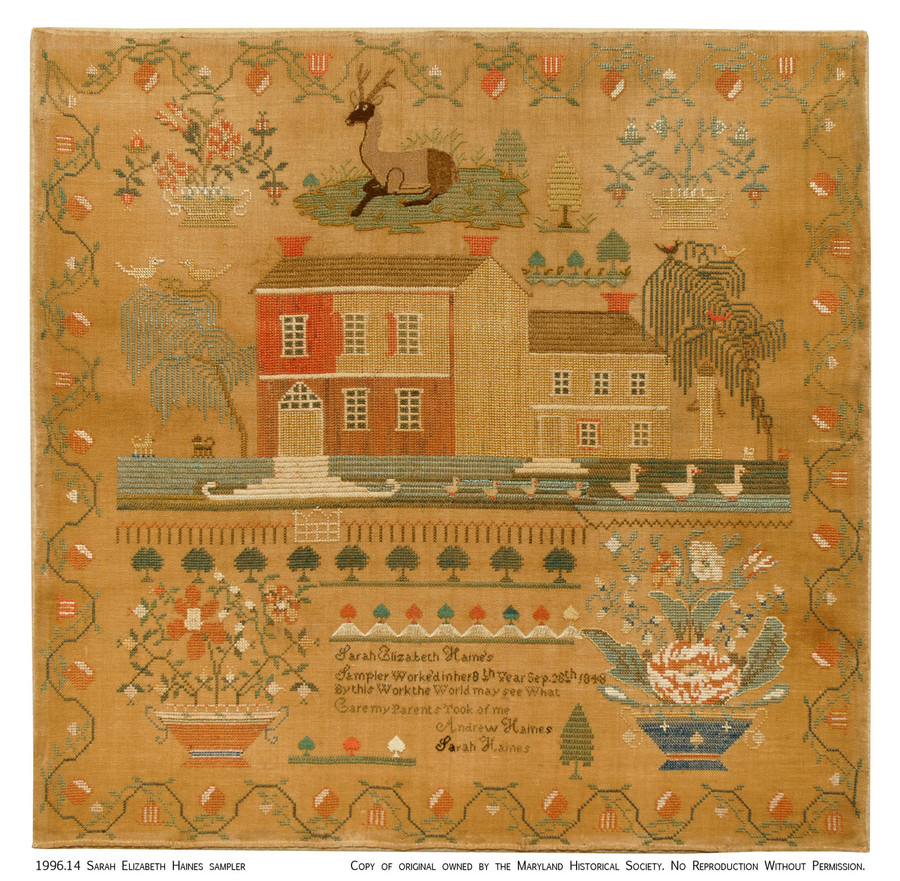

Into the nineteenth century in America, linen, being more versatile than other textiles, was often made at home for personal use as clothing, tablecloths, and bedding rather than purchased at high cost from overseas. [6] Linen was also used as the ground for needlework practice for young girls, of which we have numerous extant examples in our collection. It was also often used for men’s clothing, while women’s clothing was made from finer materials and lined with lower-quality linen.

While we still wear linen today, its production is almost entirely industrially automated. In the era of fast fashion, it is difficult to imagine how much labor used to go into not only making a garment, but producing the raw materials for clothing as well. It is important today to recognize the history of the fabrics we wear, and more importantly, how textile industries were built from a foundation of the labor of enslaved peoples.

[1] The Cottage, 4 Old Marlboro Pike, Upper Marlboro, Prince George’s County, MD, photograph from Historic American Buildings Survey with contributors Charles Claggett, Catherine C Lavoie, Jack E. Boucher, and John O. Bostrup, 1933. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C., loc.gov/item/md1183

[2] N. B. Harte, “The British Linen Trade with the United States in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries,” Textiles in Trade: Proceedings of the Textile Society of America Biennial Symposium, September 14–16, 1990, Washington, D.C., accessed November 20, 2020, digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/605.

[3] Ibid.

[4] “One spinning wheel the same as the others?,” June 1, 2017 the James Madison Museum of Orange County Heritage website, accessed November 18, 2020, thejamesmadisonmuseum.net/single-post/2017/06/01/one-spinning-wheel-the-same-as-the-others.

[5] Charlotte Jirousek“Textiles and Independence in Colonial America,” 1995, Art, Design, and Visual Thinking: An Interactive Textbook website, accessed November 09, 2020, char.txa.cornell.edu/ppeamericatex.htm.

[6] Harte, “The British Linen Trade.”

By Vivien Barnett

Curatorial Assistant