Together Again: Reuniting the Silver Tureens of Judge George Washington Dobbin

By Harrison S. Van Waes, Director of Collections

Post published December 17, 2021 and Updated April 14, 2022

When an individual passes away, their possessions are often split up amongst children or other relatives. As a result, items that were once part of a pair, or larger group, are sometimes separated, never to be reunited again. Such was the case with a set of three silver tureens owned by Judge George Washington Dobbin (1809-1891).

Dobbin was born in Baltimore on July 14, 1809, to George Dobbin (1774-1811) and Catherine Bose Dobbin (1786-1875). His father, originally of Monaghan, Ireland, arrived in Maryland in 1800 and became a citizen in 1805. The elder Dobbin was an editor and proprietor of what was then called the American and Commercial Daily Advertiser as well as a law partner in Dobbin, Murphy & Bose with his brother-in-law William Bose, and a fellow Irish immigrant named Thomas Murphy.[i]

Dobbin never knew his father, but he carried on his legacy through the field of law. Following his education at Wentworth Academy, and what was then known as St. Mary’s College in Baltimore, Dobbin enrolled in the University of Maryland Law School.[ii] After graduating, he was admitted to the Bar of Baltimore on April 2, 1830 and began to practice in the city.[iii]

With his legal career underway, he turned to marriage, family, and other pursuits. The young lawyer married Rebecca Pue Dobbin (1812-1884) on June 27, 1831.[iv] The couple initially made their home in Baltimore and Howard Counties, and over the next fourteen years had six children, all of whom survived into adulthood, which was quite an achievement in that era. Like other affluent Baltimoreans of that period, Dobbin looked to build a summer home to escape the oppressive summer city heat. In 1840, he purchased nine wooded acres along the Patapsco River, just southwest of the Thomas Viaduct. There he built a modest cottage, which he named “The Lawn.” Shortly after the home was constructed, physicians advised him to permanently move out to the country for health reasons. As a result, the house was expanded in size and two additional buildings were added during construction periods in 1845 and 1860.[v] The Dobbin’s new home location was so popular that shortly after they moved there, several other lawyers, including John H. B. Latrobe (1803-1891), built houses nearby. The area soon became known as “Lawyer’s Hill.”[vi]

An active member of the Baltimore community throughout his life, Dobbin was a founding member of the Maryland Historical Society in 1844 (now Maryland Center for History and Culture), a trustee of Johns Hopkins University & Hospital as well as the Peabody Institute, and a Director of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad among numerous other pursuits. During the Mexican-American War (1844-1846) he served as a lieutenant colonel of cavalry in the Maryland Militia. Later, he served as a dean at the University of Maryland Law School, his alma mater.[vii]

Civil War

The outbreak of the Civil War divided many Marylanders, including the residents of “Lawyer’s Hill.” Dobbin’s friend, and fellow founder of the Maryland Center for History and Culture, John H. B. Latrobe, was a staunch advocate of the colonization of Liberia and the migration of free African Americans as an alternative to abolition. Another neighbor, Dr. James Hall (1802-1889), who moved into the home “Claremont” in 1858, purportedly had a tunnel built under his home as part of the Underground Railroad for runaway slaves.[viii] Both Latrobe and Hall served terms as president of the Maryland Colonization Society. On slavery, Dobbin was known to own one slave at “The Lawn” – Benjamin Allen Chew (1827- ) – who he freed for “diverse causes and considerations” in December 1855. He otherwise employed numerous household cooks and servants over the years.[ix]

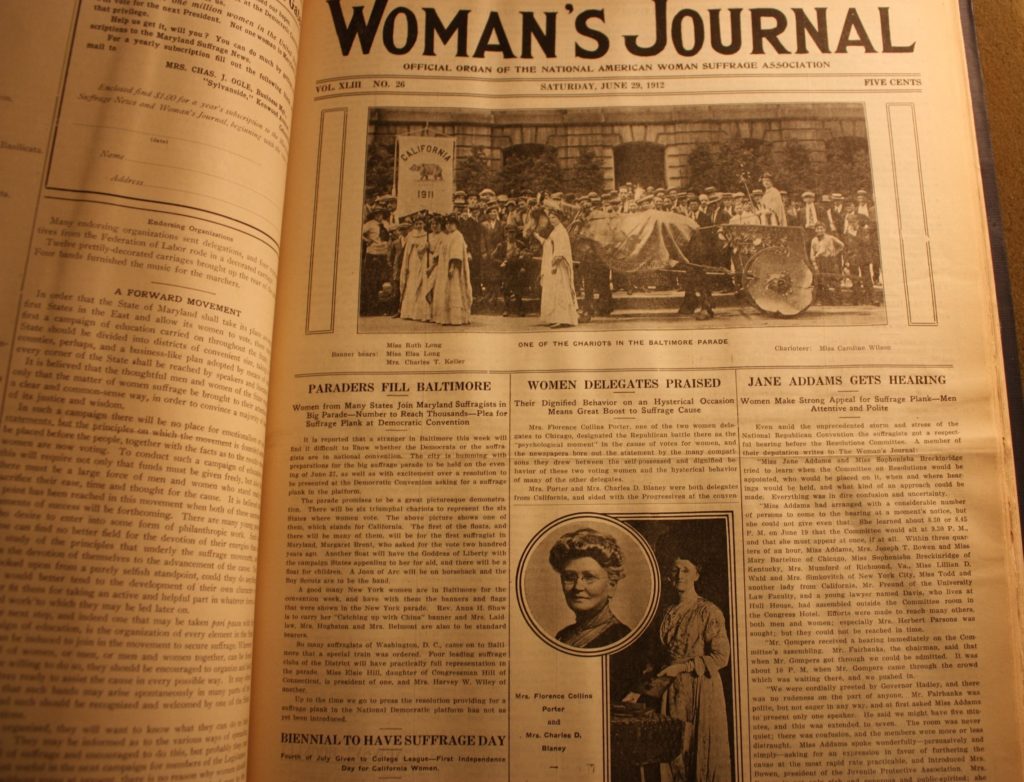

The Dobbins were known supporters of the southern cause throughout the war. In the early days following the Pratt Street Riots on April 19, 1861, Dobbin was sympathetic towards individuals caught up “in the great excitement” that led to violence or protest in and around Baltimore. Just two days later, he accompanied fellow lawyer, friend, and Mayor of Baltimore George William Brown (1812-1890) to Washington, D.C. to meet with President Abraham Lincoln so that the two leaders could discuss the atmosphere in the city and the possibilities of further troop movements in Baltimore.[x] Lincoln temporarily agreed that union troops should not pass through the city, but this was short lived as just a few weeks later the union army occupied Baltimore and held it under martial law for the rest of the war. Dobbin’s friend Mayor Brown was ultimately imprisoned at Fort McHenry for over a year due to his sympathies and actions.

A week after the riots, Dobbin was charged with prosecuting seventeen protestors who raised a rebel flag on Federal Hill and refused to take it down. After a half-hearted opening statement as the prosecution, Dobbin made “no objection to the discharge of the prisoners” and they were all freed.[xi] Shortly thereafter, he came to the legal defense of Joseph H. Spencer (1820-1889), a city merchant transporting $15,000 worth of goods to Virginia, who stopped at the army-occupied Relay House along the B&O Railroad. He verbally berated the union troops who inspected his cargo and was arrested by order of General Benjamin Butler (1818-1893).[xii] Dobbin’s daughter, Rebecca Pue Dobbin Penniman (1833-1915) later wrote bitter feelings of thieving, rude, and unsanitary troops living at “The Lawn,” which made up part of the army’s Camp Essex and union artillery positions overlooking the important Thomas Viaduct.[xiii] Like Baltimore, the Dobbin home was occupied by the union army for the duration of the war.

Post-War Years

After the war, Dobbin continued with his law practice, work at the University of Maryland, and was devoted to shaping Maryland in the post-war era. He served as a public advocate for President Andrew Johnson’s (1808-1875) Reconstruction policies, which were favorable to Democrats and former confederate states, and was made a member of Maryland’s Constitutional Convention in 1867, which included the role of chairman of the judiciary committee.[xiv] One of the provisions in the new Maryland Constitution created the Supreme Bench of Baltimore City, which oversaw five lower courts. The Superior Court was managed by five elected judges, including a Chief Judge and four associates.[xv] Dobbin ran on the Democratic ticket for one of the Associate Judge positions and beat his opponent by nearly 14,000 votes.[xvi]

Now Judge George Washington Dobbin, he took office in November 1867 with his fellow judges to begin a fifteen year term in office. In this position he commanded an excellent salary of $3,500 annually and was later awarded an LL.D by the University of Maryland. In addition to his many civic affairs, he continued his life at “The Lawn” with his family, which now included many grandchildren. In 1879, the Judge turned 70, which according to the Maryland Constitution, required his retirement from the bench. For his case, the State Legislature made an exception and he was allowed to finish out his term.[xvii]

Judge Dobbin’s Silver

In 1882, Judge Dobbin’s fifteen year term as an associate judge on Baltimore’s highest court came to an end. At the age of 72, he left office and retired from the Bar of Baltimore City after 52 years of membership. As was customary for retirement gifts of that era, the Baltimore Bar presented him with three silver tureens, made by renowned Baltimore silversmith Samuel Kirk & Son. All identical in design, two are the same size, while one is much larger. After Judge Dobbin passed away at “The Lawn” in 1891, the three pieces were split up amongst three of his four surviving children.[xviii] The largest tureen passed to his youngest daughter Mary Dorsey Dobbin Brown (1836-1895), one of the small tureens was given to his oldest daughter Rebecca Pue Dobbin Penniman (1833-1915), and the last one passed to one of his two surviving sons: Robert Archibald Dobbin, Sr. (1839-1911).

The largest tureen had the shortest route to the Maryland Center for History and Culture. Mary Brown passed it to her son Dr. George Dobbin Brown (1874-1958). In 1950, Dr. Brown donated the tureen, along with several other Brown and Dobbin family objects. It seems that knowledge of the other two Dobbin tureens was lost during or after the time of donation. In 1983, MCHC curator Jennifer Faulds Goldsborough published Silver in Maryland in conjunction with a six month exhibition of the same title. In the publication she offers this observation of the tureen:

“The maker of this heavy, handsome tureen is something of a surprise since it is almost the antithesis of the Baltimore Repousse style we associate with Kirk and Son during the 1880s. Nor is it in the so-called eclectic “Victorian” style of most American silver manufacturers of the period. It is an excellent example of how masterfully the Kirk firm could handle other styles when given the opportunity.”[xix]

Beyond these observations and other basic details, there is no information or speculation in the publication on the possibility of more than one tureen, nor is there any such information in the 1950 donor file.

In November 2020, the museum received a confusing email from a prospective donor and the great-great-great grandson of Judge Dobbin. He offered a silver tureen, identical to the one donated by Dr. Brown in 1950. The donor believed that he had the only one until he came across the catalogue entry in Silver in Maryland. After confirming that both were identical, but different in size, the donor delivered the other tureen one week later. There was great excitement on staff and within the Museum Committee of the Board of Directors regarding this acquisition. Seventy years after the donation of the first tureen, and 130 years since the tureens were split amongst Judge Dobbin’s children, the pair was reunited.

With the addition of the second tureen, Mark Letzer, President & CEO of MCHC, soon speculated that there was possibly a third tureen with this set. Through a series of communications through the MCHC Board of Directors to another Dobbin descendent, we learned that there was indeed a third example, identical to the smaller tureen, and they were interested in donating the object to the museum to complete the set. Delivered in March 2021, MCHC went from one tureen to three in just five months. After 130 years apart, and many successive generations of Dobbin-family ownership, the retirement silver of Judge George Washington Dobbin is together again, preserved at the Maryland Center for History and Culture.

[i] “Maryland Heraldry: The History of the Dobbins,” Baltimore Sun, August 19, 1906, p. 17; the newspaper later changed its name to the Baltimore News American.

[ii] St. Mary’s College was a civil school when it was established around 1805. It has been a Seminary since 1822.

[iii] American Biographical Library. Accessed at: Ancestry.com

[iv] “Maryland Heraldry: The History of the Dobbins,” Baltimore Sun, August 19, 1906, p. 17

[v] “The Lawn”, National Register of Historic Places inventory, Maryland Historical Trust https://mht.maryland.gov/secure/medusa/PDF/NR_PDFs/NR-839.pdf

[vi] Jackie Powder, “Lawyer’s Hill,” Baltimore Sun, July 21, 1991.

[vii] American Biographical Library. Accessed at: Ancestry.com

[viii] “Claremont”, National Register of Historic Places Inventory, Maryland Historical Trust. https://mht.maryland.gov/secure/medusa/PDF/Howard/HO-798.pdf

[ix] Benjamin Allen Chew’s Manumission papers are owned by the Howard County Historical Society, see Theresa Donnelly, “Freed Slaves in Howard County,” The Legacy: Newsletter of the Howard County Historical Society (2011), Vol. 48, No. 2 and Deed of Manumission, available at: Deed of manumission by George W. Dobbin for Negro slave named Benjamin Allen Chew, dated December 22, 1855 – Manumissions, Indentures, Bills of Sale – Howard County Historical Society – Digital Maryland; The 1840 census shows four free African American servants in his household. In 1850, he employed two “mulato” women and one African American male laborer. In 1860, he employed four African American servants, including a house keeper, cook, waiter, and coachman.

[x] “Statement of Mayor Brown as to his interview with Mr. Lincoln,” Baltimore Sun, April 22, 1861, p. 2.

[xi] “War Excitement in Baltimore,” Baltimore Sun, April 29, 1861, p. 1.

[xii] “The War Movements,” Baltimore Sun, May 8, 1861, p. 2.

[xiii] Elkridge Heritage Society (1983). Lawyers Hill Heritage: Elkridge – 3 Wars and the Peace.

[xiv] “To the Citizens of Baltimore,” Baltimore Sun, February 26, 1866, p. 2; “Maryland Heraldry: The History of the Dobbins,” Baltimore Sun, August 19, 1906, p. 17.

[xv] Proceedings and Debates of the 1867 Constitutional Convention, Volume 74, Volume 1, Debates 571-573.

[xvi] “Local Matters,” Baltimore Sun, October 25, 1867, p. 1.

[xvii] “George W. Dobbin”, Maryland State Archives. Accessed: https://msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc3500/sc3520/013100/013142/html/13142bio.html

[xviii] Judge Dobbin is buried at Green Mount Cemetery in Baltimore.

[xix] Jennifer Faulds Goldsborough, Silver in Maryland, p. 153

One hundred nine years ago this month, Maryland suffragists took to the Baltimore streets in a momentous march for women’s voting rights. In this blog post, Emma Z. Rothberg, Maryland Center for History and Culture’s Lord Baltimore Fellow for 2019/2020, explores the 1912 march and her experience diving into primary resource materials within the MCHC’s H. Furlong Baldwin Library.

As a born and bred New Yorker, the word “parade” used to conjure up images of blocked streets, diverted buses, and an inability to get anywhere I needed to be efficiently. Parades were something I actively distanced myself from, choosing to walk blocks out of my way to avoid the crowds rather than try to wade my way through the throng. And yet, starting in 2016 I found myself sitting in the H. Furlong Baldwin Library at the Maryland Center for History and Culture not only actively seeking out information on parades in Baltimore, but reevaluating my relationship with these large-scale events.

As I sat in the library combing through newspaper articles, photographs, and the materials of parade organizing committees, I was immediately drawn into the earnestness with which people planned and covered these parades. People believed in the power of these spectacles—the power to promote, to celebrate, to change minds. Newspapers and organizers spoke in ebullient and (to my twenty-first century ear) flowery language about how parades were the best means for accomplishing their goals. Beyond the language, the imagery of these parades was spectacular.

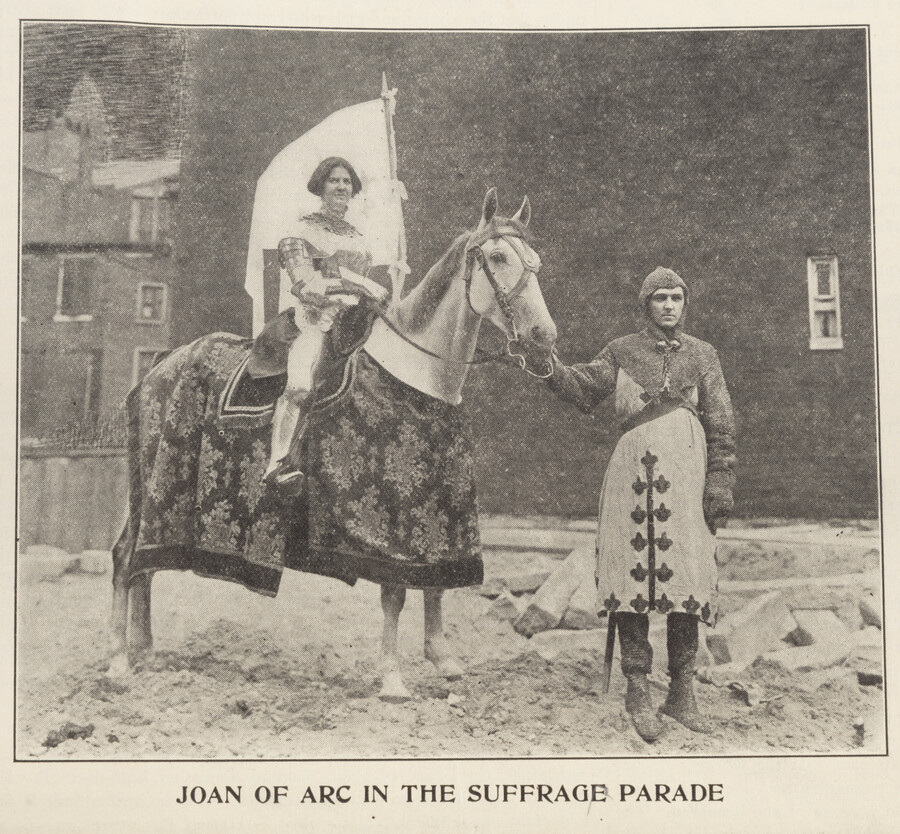

It was when I was combing through the Library’s collection of Maryland Suffrage News (MSN), a companion to the Woman’s Journal produced by the National Association of Woman Suffrage (NAWSA), that my attention was piqued by reprinted images of participants in various suffrage parades and events in 1912. There were women in costume, women on floats, women carrying banners. Why did they choose these images as the best means to advocate for their right to vote?

Maryland women had taken part in successful suffrage parades in New York City, but they were inspired to host one of their own in 1912. The MSN on May 18 told readers that the summer of 1912 “constitutes a unique opportunity for the suffragists of Baltimore, of Maryland and of all the States in the Union to draw attention to the fact that we are living in a lopsided democracy.” 1912 was an election year. The Republican National Convention was in Chicago, and suffragists were planning a parade. The Democratic National Convention was coming to Baltimore in June. The MSN argued that the most effective way to show women’s desire for the vote was if people from all over the United States came to Baltimore to march. The MSN argued, “this is the first time at a Democratic Convention that women have so far aroused from the training and the lethargy of centuries as to demand consideration as human beings. And we want the fact to be impressive.”[2]

For Maryland suffragists, a parade would be the visualization of the more equitable democracy they desired. By attaching themselves directly to political parties, women’s suffrage advocates were explicitly making claims on the democratic process. For the participants, the parade was an earnest and vital vehicle for women to prove they were equal members in a democracy. This parade allowed participants to take advantage of Baltimore’s elevated position as a space of national interest representing the democratic process to boost their own position.

As I continued to flip through the pages of MSN, furiously taking notes, I kept seeing disagreement. One objection was that a convention week was not ideal for a suffrage parade as the attending men would be too busy with other business. Another fear was that such a big stage could result in a big failure if not enough women participated. Maryland suffragists again emphasized the unique opportunity of the convention week, arguing that a parade would give the Democrats “an opportunity to prove the sincerity of their statements about ‘democracy.’”[3] Apparently these arguments worked, for the MSN reported on June 1, “the wet blanket thrown over our parade plans last week seems to be rather drying off—at least, the heat of enthusiasm underneath is such that is forced to dry off, and we shall emerge triumphant.”[4]

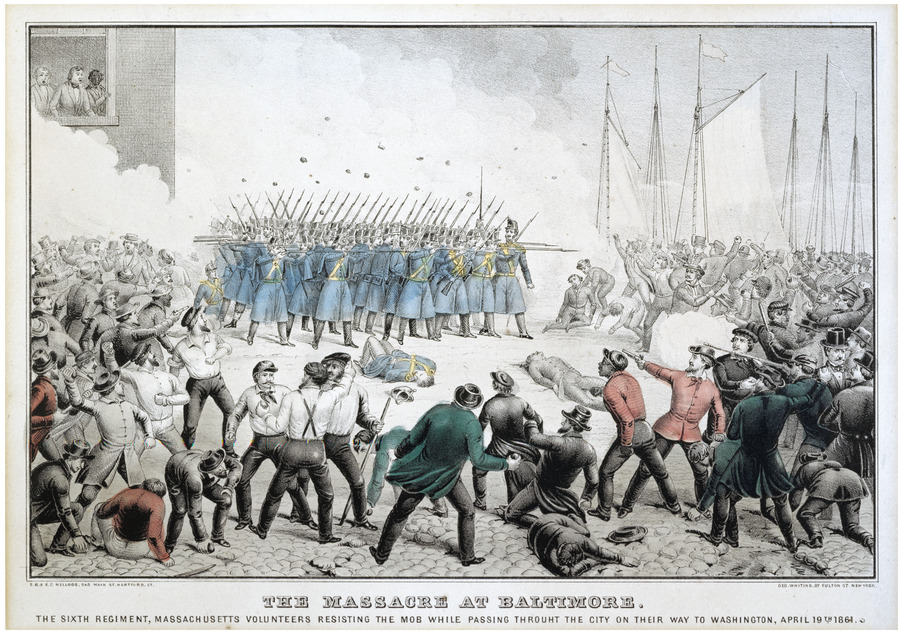

On June 28, 1912, an estimated 1,000 suffragists began their march west on Monument Street to Park Avenue and then around the Convention Hall in the Fifth Maryland Regiment Armory on Hoffman Street as roughly 15–20,000, or 50,000 according to the MSN, spectators watched from the sidewalks.[5] I realized the parade had probably passed right by the building in which I was sitting. The parade began with a “cordon of mounted policemen” and the parade’s female marshals on horses. The Baltimore Sun reported the police were there to “wreak vengeance on persons who had been promiscuous in threats to hurl tomato cans, aged eggs, et cetera, at the paraders.”[6]

As I continued to flip through the Library’s holdings of MSN, I found my first photograph of a Joan of Arc. The parade was led off by Miss Ida Baker Neepier dressed as Joan, “with her steel armor scintillating in the glare of the electric lights” she “waved her mailed hand from her seat on a show-white charger.”[7] Joan was a favorite icon for the American suffrage movement because she represented, to suffragists, a woman fighting the good fight against men who sought to oppress her. (Though suffragists did ignore her eventual torture and execution.) That Joan of Arc was historically removed from the twentieth-century suffrage movement made her image less threatening to men; women in medieval-style armor did not evoke the same gendered fears as if women paraded in more contemporary military uniforms. “Joans” appeared not only in the 1912 Baltimore parade, but in New York City, Philadelphia, and Boston suffrage parades. Most famously, leading suffragist and women’s labor advocate Inez Milholland (who was called “the most beautiful suffragette” by The Washington Post) led off the 1913 Washington, D.C., suffrage parade dressed as Joan of Arc.[8]

Another prominent visual of the parade were floats. There were floats dedicated to mothers, “Baltimore’s beauties” driving Roman chariots representing suffrage states, and the Goddess of Liberty.[9] Another float was dedicated to Margaret Brent, who Maryland suffragists claimed was the first women to “seek the franchise.” In the 1640s, Margaret Brent appeared in front of the Colonial Assembly and asked Lord Baltimore himself for a vote as a landowner.[10] The float, decorated in colors of Maryland (black and orange), had Miss Kate Ernst dressed as Brent “at the feet of Lord Baltimore (Mr. Frank F. Ramey), enthroned on high, still seeking the right of franchise.”[11] The Margaret Brent float made women’s role in the history of the United States central and emphasized that women had been fighting for the vote for centuries. In the end, Maryland was named for a woman.

I was most struck by the description of the Just Government League of Maryland’s presentation. Following behind the chariot for Utah, the “members of the Just Government League of Maryland [wore] paper shackles, designating their bondage to the tyranny of man.”[12] Another description stated the paper shackles showed “how man has bound woman in the affairs of the nation.”[13] Women were done being subtle. I was desperate to find an image, but unfortunately none accompanied the press descriptions. I am still hoping to find one.

The MSN deemed the 1912 Baltimore suffrage parade a success, calling it “The Best Parade Ever Held in Maryland.”[14] Press coverage unanimously agreed the parade was orderly, smooth, spectacular, and went a long way in convincing the crowds and the DNC of the suffrage cause. The Woman’s Journal used the terms “monster” and “triumphal” a number of times to describe the size and success of the parade. Yet the Democratic Party did not adopt suffrage in its 1912 political platform.[15]

While it did not convince the Democratic Party, the 1912 parade did help convince Maryland suffragists and the press of the advisability of parades for the movement. The MSN argued by parade’s end, “none were near to question the advisability of a parade or the ability of suffragists to unite for the good of the cause.”[16]

As I finished reading through the Maryland Suffrage News’s description, I found myself agreeing with the organizers—spectacular parades could change minds. While I will not argue the Nineteenth Amendment passed because of the proliferation of suffrage parades across the United States, I will argue parades went a long way towards persuading people—especially the men who could vote on the subject—that women were fit and capable of holding their own in the public arena. They did not need to be shielded or protected by men; they needed to be given their own voice. The power of these early suffrage parades to persuade carries resonance with us today. Particularly as we emerge from the COVID-19 pandemic and venture outside again, I will view my relationship with the theater of the streets in quite different ways.

Emma Z. Rothberg is a PhD Candidate in History at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill who focuses on urban, cultural, and gender history in the nineteenth- and early twentieth- century United States. Her dissertation examines the cultural practices of urban democracy and identity in American cities at the turn of the twentieth century. She is currently the Co-Director of UNC’s Digital History Lab and serves as the U.S. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg Predoctoral Fellow in Gender Studies at the National Women’s History Museum. Originally from New York City, Emma received her BA from Wesleyan University and MA from UNC-Chapel Hill.

[1] “The Suffrage Parade,” Maryland Suffrage News (Baltimore), Vol.1, No.10, June 8, 1912.

[2] “Suffrage Parade Planned for Baltimore—Women Will March in National Democratic Convention,” Maryland Suffrage News (Baltimore), Vol.1, No.7, May 18, 1912.

[3] “Suffrage Parade,” Maryland Suffrage News (Baltimore), Vol.1, No.8, May 25, 1912.

[4] “The Suffrage Parade,” Maryland Suffrage News (Baltimore), Vol. 1, No. 9, June 1, 1912.

[5] “1,000 Suffragettes Parade,” New York Times (New York),June 29, 1912; “The Baltimore Parade. A Brilliant Success on a Perfect Evening—Crowds, Enthusiasm and Good Nature Along the Line of March—‘The Best Parade Ever Held in Maryland,’” Maryland Suffrage News (Baltimore), Vol.1, No.14, July 6, 1912.

[6] “March Like Men,” The Sun (Baltimore), June 29, 1912.

[7] “March Like Men,” The Sun (Baltimore), June 29, 1912.

[8] Allison K. Lange, Picturing Political Power: Images in the Women’s Suffrage Movement (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2020), 170; Mary Dockray-Miller, “Why Did the Suffragists Wear Medieval Costumes?” JSTOR Daily, March 4, 2020, accessed June 15, 2021, https://daily.jstor.org/why-did-the-suffragists-wear-medieval-costumes/.

[9] “1,000 Suffragettes Parade,” New York Times (New York),June 29, 1912; “March Like Men,” The Sun (Baltimore),June 29, 1914; ““The Baltimore Parade. A Brilliant Success on a Perfect Evening—Crowds, Enthusiasm and Good Nature Along the Line of March—‘The Best Parade Ever Held in Maryland,’” Maryland Suffrage News (Baltimore), Vol.1, No.14, July 6, 1912.

[10] Margaret Brent continued to be an important figure for suffragists in Maryland. When the Just Government League held a “hike” throughout Maryland counties with their “pioneer schooner” (a covered wagon) in 1915 to convince people to vote for suffrage, they dedicated the “schooner” to Margaret Brent; See Maryland Suffrage News coveragein 1915 for more on the Margaret Brent “hike.”

[11] “The Baltimore Parade. A Brilliant Success on a Perfect Evening—Crowds, Enthusiasm and Good Nature Along the Line of March—‘The Best Parade Ever Held in Maryland,’” Maryland Suffrage News (Baltimore), Vol.1, No.14, July 6, 1912.

[12] “March Like Men,” The Sun (Baltimore),June 29, 1912.

[13] “1,000 Suffragists March,” New York Tribune (New York),June 29, 1912

[14] “The Baltimore Parade. A Brilliant Success on a Perfect Evening—Crowds, Enthusiasm and Good Nature Along the Line of March—‘The Best Parade Ever Held in Maryland,’” Maryland Suffrage News (Baltimore), Vol.1, No.14, July 6, 1912.

[15] Democratic Party Platforms, 1912 Democratic Party Platform Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project, accessed June 15, 2021, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/273201.

[16] “The Baltimore Parade. A Brilliant Success on a Perfect Evening—Crowds, Enthusiasm and Good Nature Along the Line of March—‘The Best Parade Ever Held in Maryland,’” Maryland Suffrage News (Baltimore), Vol.1, No.14, July 6, 1912.

In this blog post, Maryland Center for History and Culture (MCHC) guest contributors David Armenti, Director of Education, and Alex Lothstein, Museum Learning Manager, examine Baltimore’s history of housing discrimination and the pursuit of fair housing.

In the spring of 2020, the Baltimore City Office of Equity and Civil Rights reached out to collaborate with the Maryland Center for History and Culture for the virtual Fair Housing Festival. Staff from MCHC created a short video highlighting Baltimore’s long history of housing discrimination, which began both a partnership between the two organizations and an increased focus by MCHC to make the history of race-based housing discrimination more public. MCHC staff also participated in public programs and related interviews in a continuation of this collaborative partnership. In April of 2021, MCHC partnered with the Baltimore City Office of Equity and Civil Rights once again, along with the Baltimore Office of Promotion & the Arts, and the Baltimore National Heritage Area for this year’s Fair Housing Festival. MCHC used its collections to create an exhibit focused on housing discrimination for the outdoor exhibition entitled “Baltimore’s Pursuit of Fair Housing: A Brief History.” This exhibition will be on display at the Parks and People Foundation site near Druid Hill Park in Baltimore throughout April 2021.

Staff members for the Maryland Center for History and Culture used collections from the H. Furlong Baldwin Library to research, write, and provide materials and images for the exhibit panels. Some of this research and some of these images are included in the text below.

The public, K-12 educators, and students can access the following short video for an introduction to housing discrimination history and consequences of redlining in Baltimore: https://vimeo.com/434469938 as well as a longer discussion here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_4__O8vxPLE

Before the Civil War, Baltimore housing was reasonably diverse, with white and Black residents living around each other. However, white Baltimoreans tended to live on main streets while Black Baltimoreans primarily lived along alleyways. Following the Civil War, an increase in Black and European immigration to Baltimore, coupled with new public transportation options and the Great Baltimore Fire of 1904, began to lead to white middle-class flight. During the early 1900s, white Baltimoreans started using housing ordinances, homeowners associations, and block-busting to discriminate against and segregate Black Baltimoreans. Initially as white residents moved out of downtown Baltimore, followed by some ethnic groups, such as Jewish immigrants, there were no official housing segregation policies that stopped wealthy and middle-class Black Baltimoreans from following the same trajectory. Nevertheless, most realtors did not sell to Black families. If a Black family bought a house in a white neighborhood, the white property owner most likely sold it themselves.

In 1910 a white homeowner sold the property at 1834 McCulloh Street to W. Ashbie Hawkins, a prominent Black attorney. This sale broke the color barrier of the 1800 block of McCulloh Street. However, the subsequent rental to his law partner, George McMechen, led to white backlash and began a series of official and unofficial housing discrimination policies in Baltimore.[1]

Unofficially, this sale began a home-selling pattern in which white Baltimoreans would sell to Jewish homebuyers. Jewish homeowners would then sell, only if their neighborhood or block’s market was in a slum, to Black Baltimoreans. Once Black home buyers broke the block, many white homeowners would freely sell to Black home buyers or renters. Although this line of succession primarily took place in the old West Baltimore neighborhoods of Upton and Druid Heights, this block-breaking scared white homeowners and government officials throughout Baltimore.

One of the first official policies was Baltimore City Ordinance 610, known as the West Plan – named after Councilman Samuel West. This ordinance, passed by the City of Baltimore in December of 1910, stated that no Black resident could move on to a block in which more than half of the residents were white and vice versa. The West Plan did have a provision stating that existing conditions would not be disturbed, and no homeowners needed to move out of their neighborhood.[2] While Ordinance 610 was the first of three race-based housing ordinances in Baltimore, many cities across the United States and even the world modeled similar discriminatory laws after the West Plan. Nevertheless, the Supreme Court deemed civil government-instituted housing segregation laws unconstitutional in 1917 with Buchanan v. Warley.[3] However, in its seven years of existence, Ordinance 610 led to race-based predatory lending policies and housing lines dictated by race that still exist today.

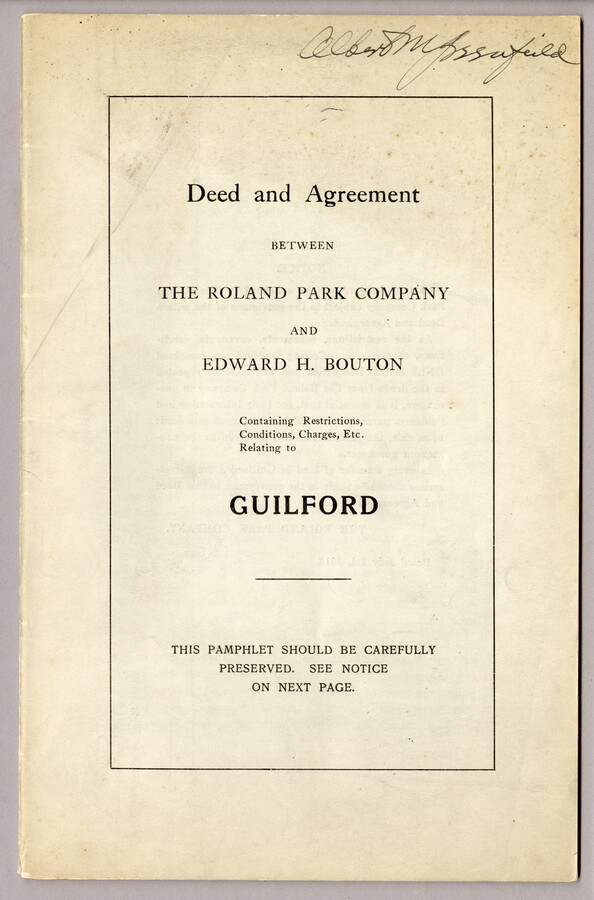

While Ordinance 610 was a government-sponsored housing segregation law, many private Baltimore communities instituted community covenants that restricted Black Marylanders from moving into the neighborhood. One example was the Guilford neighborhood, planned and designed by the Roland Park Company. In a section within the Roland Park Company’s Guilford Neighborhood Covenant from 1913 entitled “Nuisances,” a provision stated that “at no time shall the land in said tract or any part thereof shall, or any building erected thereon, be occupied by any Negro or a person of Negro extraction.” The covenant did make an exception for Black domestic servants to white families.[4]

Covenants and housing ordinances forced many Black families into neighborhoods that consistently suffered from unequal resources and lack of investment. This discrimination led to lower home values and challenges in accumulating wealth. However, some neighborhoods for upwardly mobile Black families, such as Morgan Park or Cherry Heights, advertised as having lots as beautiful as Roland Park.[5] The second was, coincidentally, established by a realty company represented by lawyers George McMechen and W. Ashbie Hawkins. It was not until 1948 that the Supreme Court ruled in the Shelly v. Kramer case that restrictive private covenants were unconstitutional and violated citizens’ 14th Amendment rights.[6]

In 1937, the Federal Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) published its Residential Security Map of Baltimore. This map graded the lending risk factors and desirability of neighborhoods in Baltimore and many other American cities. While initially part of the New Deal’s National Housing Act of 1934, intended to help prevent foreclosures, the maps soon became a symbol of race-based housing discrimination.

You can view this Residential Security Map from 1937 via Johns Hopkins Sheridan Libraries Digital Collections: https://jscholarship.library.jhu.edu/handle/1774.2/32621.

Areas in Green (Grade A) were the most desirable, followed by Blue (Grade B), Yellow (Grade C), and finally Red (Grade D). Grade D neighborhoods were considered the least desirable or riskiest for investment. While white neighborhoods tended to fall within the green and blue grades, most of Baltimore’s Black neighborhoods, including some immigrant neighborhoods, particularly those in East and South Baltimore, were almost exclusively “redlined.” Black neighborhoods in Baltimore suffered from high rents and poor-quality housing, and limited social and city services, leading to Grade D markings. The HOLC maps showed a bias against Black Marylanders, immigrants, and blue-collar communities. Despite this, real estate brokers, mortgage lenders, and other entities consulted the HOLC maps produced for urban centers across the country. The effects led to further deterioration of many minority and working-class communities and encouraged discrimination against their residents.[7]

Despite the legal victories, race-based housing policies would continue to be present following the 1937 HOLC map. At the turn of the 20th century, migration by African Americans, Native Americans, and white people moving from the South increased Baltimore’s population. Around 175,000 new residents arrived in the 1910s and ’20s. The Great Depression and World War II exacerbated this trend. Wartime industries such as ship and airplane production provided new economic opportunities, though not equal to everyone, as Black people moving to Baltimore faced significant discrimination in employment and housing.[8]

The wartime population surge created an immediate housing and resource shortage in the city. Companies like Glenn L. Martin and Bethlehem Steel invested in temporary housing. However, they restricted the housing to white defense workers and their families. In 1941, the only available housing for Black defense workers were the Poe Home projects; however, the McCullough Homes were nearing completion. Housing for Black Marylanders was often overcrowded, and many of the buildings had deteriorated to the point of being unsafe for occupancy. Federal Public Housing Authority plans were approved to build housing for Black workers near Herring Run Park and the Brooklyn community.[9] However, mass protests by white residents caused the abandonment of these plans. Ultimately, the city developed an unoccupied tract of land in South Baltimore into the Cherry Hill neighborhood.[10] Hundreds of permanent houses were built for Black defense workers, many of which still stand today. Baltimore City’s population would reach its all-time peak shortly after the war, with 949,708 residents tabulated in the 1950 U.S. census. Despite the population boom, the city continued to hem the African American population into segregated areas, often forced to live in older structures. At the same time, white residents took advantage of newer housing developments in growing suburban areas.[11]

In the mid to late 1950s, to alleviate overcrowding in Black neighborhoods, Baltimore City built a series of high-rise, public housing developments. Although the city claimed these homes were designed for working-class residents, many Black Baltimoreans saw these developments (Lafayette Courts, Flag House Courts, the Murphy Homes, and the Perkins Homes) as a way to segregate African Americans further rather than provide homes for the working class. Initially, these new homes represented an improvement from life in dilapidated slum housing, with many projects offering community programs, swimming pools, and other activity centers. However, between 1955 and 1990, Baltimore’s high-rise developments suffered from disrepair and neglect from the city and tenants, a lack of investment, and crime. As a result, throughout the 1990s, Baltimore City began demolishing the high rises, with Lafayette Courts falling in 1995, Flag House Courts and the Murphy Homes in 1999, and Perkins Homes in 2019. The city built mixed-income housing to replace the structures in many of these communities. Nevertheless, housing discrimination still exists in Baltimore, whether by the city or by private lenders.[12]

On April 11, 1968, seven days after Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1968. Title VIII of the act, commonly referred to as the Fair Housing Act (FHA), provided “fair housing to all persons regardless of race, color, religion, sex, or nationality.” The FHA deemed activities such as refusing to rent, sell, or show homes and directing buyers to homes based on the buyers’ race, color, religion, sex, or nationality illegal. The FHA also criminalized advertisements that showed a preference to buyers or renters of a certain race or origin. Furthermore, the FHA protected homebuyers from predatory home loan lenders.[13]

Nevertheless, Black Baltimoreans still suffered from housing discrimination. In 2008, during the Great Recession, Baltimore City became the first city to use the Fair Housing Act to sue a home loan lender, Wells Fargo. The city successfully argued that the bank targeted Black neighborhoods with subprime mortgages. In 2012, a judge ordered Wells Fargo to pay a settlement of $175 million.[14]

Consistent housing discrimination and unethical practices by landlords, the City of Baltimore, and lenders limited the ability of many in the Black community to accumulate wealth. Simultaneously, they were stigmatizing neighborhoods, decreasing the number of social programs, limiting access to public works, and heightening the police presence in those areas deemed undesirable. Although the 1968 Fair Housing Act outlawed discrimination of this type, the legacy and continued unequal treatment still impacts communities today. The effects of housing discrimination in Baltimore can still be seen in the residential maps of Baltimore today. Many of the neighborhoods where people of color live today in Baltimore are the same neighborhoods into which landlords, and lenders forced Black Baltimoreans during the earlier half of the 20th century.

David Armenti is a lifelong resident of Maryland, and a graduate of Baltimore Polytechnic Institute (Poly). He currently lives in the Mt. Washington neighborhood with his wife and two young daughters. David enjoys playing and watching sports, eating ice cream, and debating current events and cultural happenings with friends.

Alexander Lothstein holds a Bachelors and Masters in History and has resided in Columbia, Maryland for almost four years. While not a native of Maryland, he has grown to appreciate the state, its history, cuisine, and, especially, flag! Outside of the museum, Alex enjoys hiking in western Maryland, taking part in reenactments of the American Revolution, and traveling around the world.

Research was drawn from a variety of primary and secondary sources, including Not In My Neighborhood, the Baltimore Afro-American newspaper archives and the Baltimore Sun archives, as well as the collections of the H. Furlong Baldwin Library.

A primary source document packet with additional resources can be accessed upon request to educationprograms@mdhistory.org.

Readers of all ages should consult Antero Pietila’s Not In My Neighborhood: How Bigotry Shaped A Great American City for a comprehensive investigation of housing discrimination and its impact in Baltimore.

Sources and further reading:

[1] Antero Pietila, Not in My Neighborhood: How Bigotry Shaped a Great American City, Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2010, pg. 15.

[2] “Baltimore Tries Drastic Plan of Race Segregation: Strange Situation Which Led the Oriole City to Adopt the Most Pronounced ‘Jim Crow’ Measure on Record.” New York Times (1857-1922), Dec 25, 1910.

[3] Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 82 (1917).

[4] “Deed and Agreement between the Roland Park Company and Edward H. Bouton Containing Restrictions, Conditions, Charges, etc. Relating to Guilford, Roland Park Company, 1913. Maryland Center for History and Culture, H. Furlong Baldwin Library, PAM 5647

[5] “Display Ad 1 — no Title.” Afro-American (1893-1988), Dec 25, 1909.

[6] Shelly v. Kramer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948).

[7] Residential Security Map of Baltimore. Found in Records of the Federal Home Loan Bank Board, 1937, U.S. National Archives, Record Group 195, Box 106. Digital Record accessed: jscholarship.library.jhu.edu/handle/1774.2/32621 .

[8] U.S. Census Bureau. Population Density, 1910 and 1920.

[9] “FPHA Approves 4 Sites Recommended by HAB in Housing of Negroes: Work Will Be Publicly Financed – Federal Agency Drops Suit for Condemnation of Moore’s Run, Philadelphia Road Location.” The Sun (1837-1987), Oct. 26, 1943.

[10] “State Official, Congressman Protest Site; 100 Urge Action: Project Won’t Remove Slums, Baldwin Says; Suggests Trailer Camp.” Afro-American (1893-1988), Jul 31, 1943. “Cherry Hill Homes to Open on May 1.” Afro-American (1893-1988), Feb 03, 1945.

[11] U.S. Census Bureau. Population Density, 1950.

[12] JoAnna Daemmrich The Sun, Staff Writer. “An End and a Beginning for Residents: Lafayette Courts Demolition Nears.” The Sun (1837-1995), Jul 27, 1995. CHARLES COHEN. “Destroying a Housing Project, to Save it.” New York Times (1923-Current File), Aug 21, 1995.

[13] “Fair Housing Act.” The United States Department of Justice, August 6, 2015, justice.gov/crt/fair-housing-act-2.

[14] Broadwater, Luke. “Wells Fargo Agrees to Pay $175M Settlement in Pricing Discrimination Suit.” Baltimoresun.com, 10 Dec. 2018, baltimoresun.com/news/bs-xpm-2012-07-12-bs-md-ci-wells-fargo-20120712-story.html.

Marylanders over the age of forty smile brightly and recall fond memories whenever the name “Hutzler’s” is mentioned. Hutzler Brothers Company, established in 1858, was the product of three innovate brothers and dozens of their descendants. During the American Civil War, Hutzler’s experimented with the nation’s first bargain counter, and later, were the first to establish “one pricing”, which replaced the then-standard policy of customers haggling or bidding on goods with the store clerk to determine cost. In 1874, Hutzler’s created a horse-drawn wagon delivery service, and by the turn of the century, offered “same day service” with their fleet of trucks. The North Howard Street store expanded and remodeled numerous times over the company’s first ninety years. In 1952, the company expanded to Towson, Maryland. At the height of their operation, Hutzler’s owned ten stores in and around Baltimore and as far away as Salisbury. After many years of slow and steady decline, Hutzler’s finally closed their doors in 1990.

Last fall, staff in the museum and library worked together to curate The Hutzler’s Experience: How a Small Dry Goods Store Became a Maryland Institution. After announcing this upcoming exhibition, located in the H. Furlong Baldwin Library alcove, staff received dozens of emails and phone calls from Marylanders recalling their Hutzler’s experience shopping with parents and grandparents, sharing vivid details of specific food dishes consumed in the Towson location’s dining room, and offering numerous donations of Hutzler’s ephemera or products. On Facebook, users left hundreds of comments recalling the beloved department store. Among the many donation offers to the museum was a stunning bronze eagle medallion.

On August 25, 1931, Hutzler’s announced the expansion of their store on N. Howard Street. The five-story structure would add 50,000 square feet of retail space to the existing store. It was designed by the office of Baltimore architect Joseph Evans Sperry (1854-1930), who designed the iconic Bromo-Seltzer Tower in Baltimore among many other public buildings in the city. The new structure offered “a restrained modern type of architecture, with a base of iridescent pearl granite ornamented with Allegheny metal, surmounted by shaded brick trimmed with Alabama limestone.” Both the interior and exterior of the existing “Palace” building were remodeled to match this new addition. The new and old structures were connected by a series of enclosed “bridges” built over top of Clay Street. Construction by Consolidated Engineering Company began on September 15 and Baltimore’s first and only art-deco tower was completed by the following holiday season. Matching Hutzler’s history for innovation, the tower was the first building in Baltimore to be electrically welded. In 1942, an additional five floors were added and 50,000 people attended the grand re-opening of the store.

The modern interior matched the grandeur of the exterior. Bronze decorations and eagle motifs were used throughout the store. One of these decorative eagle medallions, now in the collection at the Maryland Center for History & Culture, was once affixed to elevator doors in the tower. In 1984, much of the Howard street store location closed for the final time. By 1985, the interior was gutted and renovated for office space. Most of the original 1930s fixtures were scrapped or sold at auction. After Hutzler’s closed in January 1990, they liquidated all assets and the medallion was sold at auction.

The Hutzler store on North Howard Street still stands today. Above the art deco tower revolving-door entrance, a passerby can still see what is left of the stunning bronze design that once adorned the interior of this important example of Baltimore architecture. The bronze eagle medallion, an extremely rare and important artifact, is now a part of the museum collection and on exhibit in The Hutzler’s Experience: How a Small Dry Goods Store Became a Maryland Institution.

By Harrison Van Waes, Associate Registrar

Sources:

“Hutzler Company to Build Addition: Construction of New Unit at 220-224 N. Howard Street to Begin Next Month.” Baltimore Sun, August 26, 1931, p. 3.

Lisicky, Michael J.. Hutzler’s: Where Baltimore Shops. United States: Arcadia Publishing Incorporated, 2009.

Post published September 29, 2022

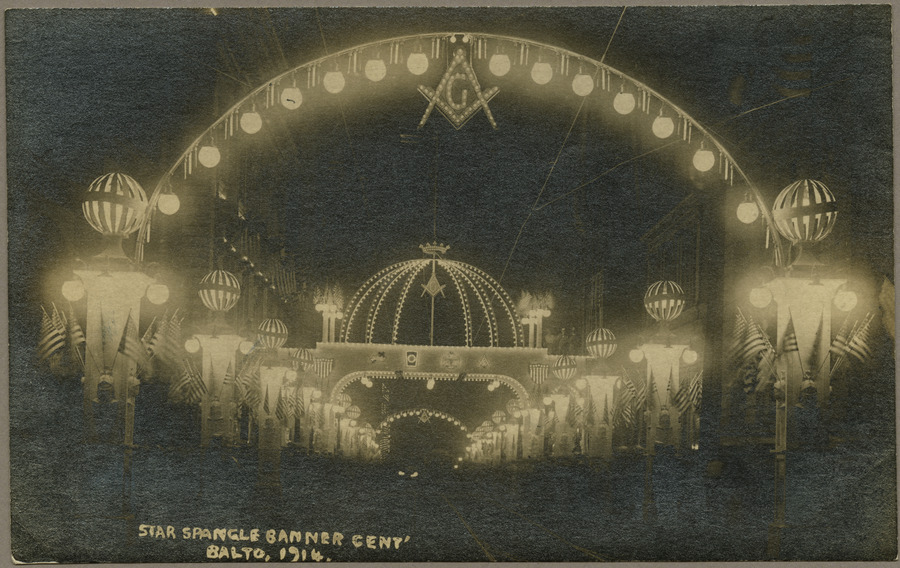

One hundred eight years ago this fall, the city of Baltimore played host to the Star-Spangled Banner Centennial Celebration. This was a week-long commemoration ostensibly aimed at promoting patriotism and respect for the American flag but importantly—and perhaps less known—an event also aimed at bolstering the image of the city of Baltimore. In this blog post, Emma Z. Rothberg, PhD, Maryland Center for History and Culture’s Lord Baltimore Fellow for 2019/2020, explores the 1914 celebration and her experience diving into primary resource materials within MCHC’s H. Furlong Baldwin Library.

Baltimore was abuzz on Monday, September 7, 1914. The day before, Baltimoreans had gathered in churches to hear sermons on patriotism, seen a concert in Druid Hill, watched boat races on the Patapsco River, and reveled as their city lit up in a fantastical light show. This morning, however, there was to be a grand parade through central Baltimore. The people who lined the streets expectantly for the 10 am start time were excited to see the floats and marching organizations representing Baltimore’s industrial and civic landscape. Some may have wondered which float in the industrial section of the parade would win First Prize ($250) and best decoration ($250); others were interested in cheering on marching laborers, athletic clubs, or—perhaps—the marching group of female suffragists. The waiting spectators were abuzz with anticipation.

From September 6 to 13, 1914, Baltimore was the site of a spectacular celebration honoring the 100th anniversary of the Battle of Baltimore and the penning of “Star-Spangled Banner” by Francis Scott Key. Baltimore’s Mayor James H. Preston first suggested the centennial celebration in 1913. He hoped the celebration of an event of such national importance would instill patriotism and respect for the American flag in the nation.[1] To that end, the Star-Spangled Banner Centennial Celebration week was full of monument and historic plaque dedications, historical exhibitions and speeches at various institutions across the city, a recreation of the bombardment of Fort McHenry (in fireworks), and the arrival of historic ships in Baltimore’s harbor. Military and naval organizations received their own day to parade as did the Star-Spangled Banner itself (President Woodrow Wilson, members of his cabinet, governors, 100 representatives of each state in the union in 1814, and Civil War veterans all escorted the flag during the Star-Spangled Banner Legion parade on September 12).[2]

But the Star-Spangled Banner Centennial was much more than a celebration of this historic moment and of the song that became the national anthem in 1931. The celebration was a major booster event for Baltimore. It is this aspect of the celebration that struck me the most as I read through the H. Furlong Baldwin Library‘s archival holdings of the event. Why was an economic booster event so important in this moment? And why connect it, or—if I was less generous—mask it, using a national event? The most likely answer is that the Baltimore of 1914 was a city still in recovery.

On the morning of Sunday, February 7, 1904, a fire broke out on the fourth floor of the six-story John E. Hurst & Co. wholesale dry goods store on the southwest corner of Hopkins Place and German Street (20 Hopkins Place). As firefighters responded, a strong wind carried the flames and embers across the business district. The exceedingly hot flames were too much for the firefighters’ hoses, and they spread quickly throughout the non-fireproof buildings downtown. Eventually, the fire burned roughly 140 acres, or 80 city blocks, at the heart of the waterfront and business district to the ground; the “burnt district” lay in ashes.[3]

The fire was devastating not only because of the physical destruction and emotional toll it took on Baltimore’s residents, but because it decimated one of Baltimore boosters’ main selling points—economic opportunity in the city. Baltimore had been combating its image as the “little sister” of larger American cities since the end of the nineteenth century. During the Baltimore Sesquicentennial in 1880, organizers too used Baltimore’s businesses to boost the city and combat its image as a “branch office town.”[4] Baltimore’s business and political leaders wanted to market the city as a solid and safe investment, a city ready to be an economic leader.[5] The destruction of the business district in 1904 was a setback to this decades’ long sales pitch, but Baltimore’s economic and political leaders were ready to dust themselves off (in some cases literally, if they had been too close to the ash) and get back to work.

The recovery was slow and expensive but also successful. Mayor McLane appointed a 63-member Citizens Emergency Committee to devise a rebuilding program for the “burnt district”; its chairman was a local industrialist, and the commission was made up of Baltimore’s elites. Yet the fire was also a catalyst for urban development and civic engagement—streets were widened and repaved, public spaces rebuilt, and a sewer system constructed. In September 1906, a year before the rebuilding was fully complete, the week-long Greater Baltimore Jubilee and Exposition celebrated the city’s recovery.[6] But 1914 was an opportunity to a put a national spotlight on this recovery and the economic promise Baltimore once again represented.

Now someone could read the documents of the Star-Spangled Banner Centennial and think, “what an over-the-top celebration.” I certainly expected that when I first began reading the meeting minutes of the Commission planning the celebration. But as I looked through the minutes and the programs, I started to notice a pattern.

Because of their symbolic resonance, I focused my search on the parades that served as the main event each day of the week-long celebration. Parades were part of a time-honored tradition for marking and celebrating civic achievements and events. Parades were a common feature of Independence Day celebrations and the opening of civic infrastructure projects—such as canals, bridges, and buildings—across the country. Fire companies, veterans, and political and fraternal organizations also all frequently turned to parades as a way of showcasing and promoting themselves. The Star-Spangled Banner Centennial organizers must have been aware of these parading traditions and a parade’s ability to create and instill a collective identity amongst participants and observers. Baltimore already had its own substantial parading tradition as a main feature of large-scale civic events.

Because of their symbolic resonance, I focused my search on the parades that served as the main event each day of the week-long celebration. Parades were part of a time-honored tradition for marking and celebrating civic achievements and events. Parades were a common feature of Independence Day celebrations and the opening of civic infrastructure projects—such as canals, bridges, and buildings—across the country. Fire companies, veterans, and political and fraternal organizations also all frequently turned to parades as a way of showcasing and promoting themselves. The Star-Spangled Banner Centennial organizers must have been aware of these parading traditions and a parade’s ability to create and instill a collective identity amongst participants and observers. Baltimore already had its own substantial parading tradition as a main feature of large-scale civic events.

The pattern I noticed was the focus on industrialism. Two of the week’s parades—Monday’s Industrial and Civic Parade and Thursday’s 8 pm Historical Pageant parade—highlighted the theme. The industrial section led off Monday’s parade; included in the section were floats for both national (like Rockefeller’s Standard Oil) and local companies (like the Maryland Ice Cream Co.). The fact that industry was the first section of the first parade of the week meant that organizers felt industrialism was the most important theme of the week. Symbolically, that struck me as odd given the Centennial was of an historic event. Similarly, the Historical Pageant was split into two parts: the First Division was the “Events of 1814,” and the Second Division was “One Hundred Years of Progress.” The “progress” visualized by the Historical Pageant’s second division was an industrial one. Floats included in this section were dedicated to the Industries of Maryland, Commerce by the Canal, the Laying of the Cornerstone of the B&O, and the Rebuilding of Baltimore (after the Great Fire of 1904 float). Not included in this progress section was the end of slavery in Maryland, the expansion of civil and political rights, or the question of the vote—a particularly interesting omission to me given that there was a Suffrage Section in the civic division of the Industrial and Civic Parade on Monday. But maybe I shouldn’t have been too surprised; Maryland was a border state during the Civil War and retained slavery until the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment. Maryland’s General Assembly had been attempting to limit the franchise for much of the twentieth century to white men only.[7]

In a letter printed on Mayor’s Office letterhead included at the front of the National Star-Spangled Banner Centennial Official Program and the Story of Baltimore (1914), published by the National Star-Spangled Banner Centennial Commission, Mayor Preston wrote “To Our Visitors”:

The people of Baltimore join with you in paying patriotic tribute to the Flag of our country, and to the heroes, the shedding of whose blood has made that flag so sacred. We want you to know our city—big, enterprising, progressive, success; we want you to know our people—hospitable, courteous, patriotic, chivalrous; we want you to know our history—important, creditable, nation-wide in its influence.[8]

The Star-Spangled Banner Centennial Celebration is an example of the ways in which patriotism and capitalism were, in many ways, intertwined in the United States. What the organization of the parades posited was that to be patriotic was to be a good investor or consumer. Buy American! Or, more specifically, buy (into) Baltimore! Based on the descriptions and the photographs of the event, it was a dynamic sales pitch.

Emma Z. Rothberg received her PhD in History from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 2022, where her research focused on urban, cultural, and gender history in the 19th and early 20th century United States. Her dissertation examined the cultural practices of urban democracy and identity in American cities at the turn of the 20th century. Dr. Rothberg is now the Associate Educator, Digital Learning & Innovation at the National Women’s History Museum. Originally from New York City, she received her BA from Wesleyan University and MA from UNC-Chapel Hill.

[1] “Series Description, Information on BRG15-(National Star Spangled Banner Centennial Commission),” Baltimore City Archives, accessed September 29, 2022, http://guide.msa.maryland.gov/pages/series.aspx?ID=BRG15

[2] National Star-Spangled Banner Centennial Commission, “National Star-Spangled Banner Centennial, Baltimore, Maryland, September 6 to 14, 1914. Official Program and the Story of Baltimore” (1914), 90-113, https://archive.org/details/nationalstarspan01nati/page/n13/mode/2up

[3] Matthew Crenson, Baltimore: A Political History (Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, 2017), 333. For more see Peter B. Peterson, The Great Baltimore Fire (Baltimore: Maryland Historical Society, 2004).

[4] Crenson, 313.

[5] For more, see Emma Z. Rothberg, “‘The Wealth and Glory of the City’: Displays of Power in Baltimore’s Sesquicentennial,” Maryland Historical Magazine 115, no. 2 (Spring/Summer, Fall/Winter 2020), 63–99.

[6] Crenson, 333.

[7] By 1911 there had been a series of drafted amendments meant to strip Black men of the franchise, including: the 1904 Poe Amendment (defeated by referendum); 1909 Straus Amendment (defeated by referendum); the Grandfather Clause in the Annapolis city code (successfully stripped Black men of the vote in the city until the Supreme Court declared it unconstitutional in 1915); and the 1911 Diggs Amendment (defeated by referendum). In terms of women’s right to vote, Maryland women received it when the 19th Amendment was ratified in 1920. Maryland itself had rejected the amendment in 1920 and would not ratify the 19th Amendment until 1941.

[8] National Star-Spangled Banner Centennial Commission, “National Star-Spangled Banner Centennial, Baltimore, Maryland, September 6 to 14, 1914. Official Program and the Story of Baltimore” (1914), 9, https://archive.org/details/nationalstarspan01nati/page/n13/mode/2up

By Vivien Barnett, Curatorial & Collections Assistant, and Sandra Glascock, Special Collections Archivist

Post published June 22, 2022

On Saturday, June 25, 2022, many Marylanders will gather on North Charles Street to view the Baltimore Pride Parade: a joyous event where members of the LGBTQ+ community can celebrate who they are. This will be the first time that Baltimore Pride has taken place since 2019, and you can read more about the series of events that will be taking place throughout the city here.

June is celebrated nationwide as Pride Month in recognition of the 1969 Stonewall uprising in New York City, which was a series of protests by members of the LGBTQ+ community against police raids and harassment that was monumental in advancing the gay liberation movement. Today, parades, parties, and other celebrations occur in cities across the country throughout the month of June to honor those who fought for the right to love who they love, and to be who they are. To celebrate this year’s Pride Month, we want to showcase some of the LGBTQ+ materials found within the Maryland Center for History and Culture’s Museum and Library collections.

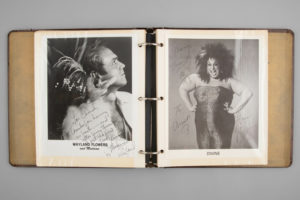

For decades, only a few blocks away from the MCHC campus, people would gather to drink, flirt, and dance the night away at Club Hippo. In addition to being a nightlife hotspot, Club Hippo was a safe haven for members of Baltimore’s LGBTQ+ community, as its motto for 40 years was “Where Everyone is Welcome.” The Hippo closed its doors in 2015 and the building has since been repurposed into a CVS Pharmacy, but the spirit of the club’s mascot, the pink hippo, lives on in the hearts of many who frequented the establishment. The iconic Hippo sign will be on display in Discover Maryland until this fall; come take your picture in front of the sign and share your memories of the club before it comes down!

The library has a collection of photographs and ephemera donated by the club’s owner, Charles L. “Chuck” Bowers, and DJ Farrell Maddox. One of the highlights is a scrapbook containing autographed headshots from performers who appeared at the Hippo, including one from drag icon and Baltimore- native, Divine. Born Harris Glenn Milstead (1945-1988), the actor and recording artist began performing in friend and fellow Baltimorean John Waters’ underground movies during the 1960s. The 1988 film “Hairspray” marked Divine’s breakthrough into mainstream cinema, but he unfortunately passed away only a month after the Baltimore premiere. Upon his death, People magazine named him the “Drag Queen of the Century,” and his impact on pop culture continues to be felt well into the 21st century.

Devin Cherubini originally came to Baltimore to study at the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA), but eventually found a home at Club Hippo; he would often complete his homework at the bar before the crowds poured in. Devin was also one of the first drag kings to perform in Baltimore in the early 1990s. Dressing up in costumes and dancing to the music of David Bowie and Nine Inch Nails, he views his drag as an art form. This 1970s themed outfit was just one of many costumes that he wore while performing under the name Devin Hellfire. He was also a member of the band Transexual Fetus, which consisted entirely of transgender musicians that performed in Baltimore.

Derrick Smith is another Baltimore drag performer who uses clothing and accessories to craft his drag persona, Mother Helena, the Queen of Gospel. Drag queens often sew and embellish their own garments, but wigs and shoes like these size 10 heels are bought at stores to complete the look. Today, Baltimore is host to many drag events, including brunches, dinner shows, and other performances.

Merrick Moses transitioned from female to male during 2014-2017, and he donated objects to the museum to represent his story. The wearing of chest binders to minimize the appearance of breasts is a common gender-affirming practice for trans individuals, while taking testosterone is a part of the medical transition. About this donation, Merrick said, “The chest binder was my first binder. I bought it for myself for my 40th birthday. I finally got the courage to bind after being so dysmorphic from 2011-2014. When I put it on for the first time, I felt I had a new lease on life. Finally, my body was beginning to look like how I felt inside, masculine.”

Stories involving the fight for civil rights for members of the LGBTQ+ community are also represented in the MCHC collections. Mark Procopio has dedicated his life to attaining equality, access, and opportunity for all people regardless of race, gender identity, and sexual orientation. He served as the Executive Director of FreeState Justice, a statewide LGBTQ+ civil rights advocacy and legal aid nonprofit in Maryland. The Mark Procopio Collection consists of newspaper clippings, documents, brochures, pamphlets, bumper stickers, and audiovisual material related to various LGBTQ+ activist organizations in Maryland. These items were used by advocacy groups such as Equality Maryland and FreeState Legal to spread awareness and information on civil rights issues facing the LGBTQ+ community, especially in regards to marriage equality.

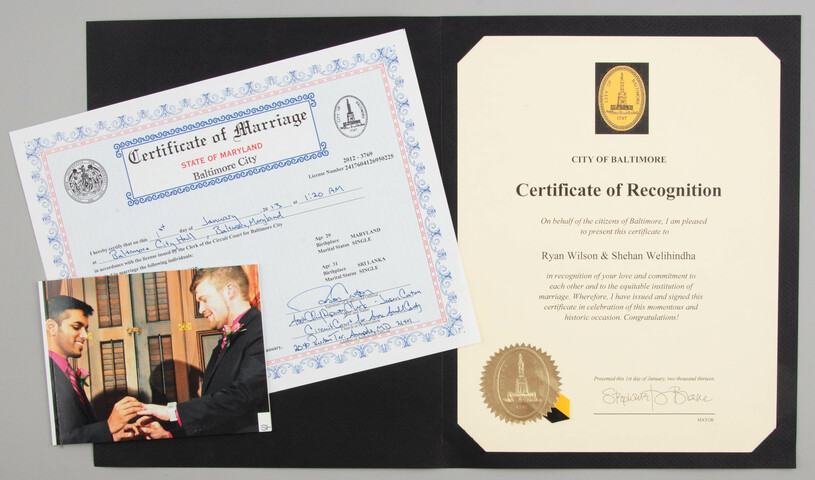

In 2012, Equality Maryland was part of the coalition that passed the Civil Marriage Protection Act allowing same-sex couples to marry, making Maryland the first state south of the Mason-Dixon line to legalize same-sex marriage. Upon learning of the passing of the Civil Marriage Protection Act and that it would take effect on New Year’s Day of 2013, Ryan Wilson and Shehan Welihindha decided to travel to Wilson’s home state in order to wed. They were living in Columbia, South Carolina at the time and could not legally marry there because in 2006, South Carolina voters approved a constitutional amendment banning nuptials between same-sex couples. The Wilson-Welihindha Marriage Papers contains materials related to their wedding ceremony performed at Baltimore City Hall, which was one of the first same-sex marriages to take place in the State of Maryland on January 1, 2013. Included in the collection is the original City of Baltimore Certificate of Marriage for the couple as well as a Certificate of Recognition signed by Baltimore Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake.

It is important to us that all Marylanders see themselves reflected at MCHC. In highlighting these objects and the stories behind them, we aim to amplify the voices of those who were previously unheard and excluded from the historical record. If you would like to donate objects that would help us to tell the story of Maryland’s LGBTQ+ community, please visit our “Item Donations” page on our website for more information on our donation process. For museum objects, please email our Museum team at museum_dept@mdhistory.org and for library donations, please email our Special Collections team at specialcollections@mdhistory.org.

Inspired by the Craftsmanship of Annie G. Dunton

by Barbara Meger, Museum Volunteer

I am fascinated by anything related to textiles—costume, needlework, lace, couture fashion, dressmaking, quilting, etc. As a volunteer curatorial assistant at the Maryland Center for History and Culture, I am privileged to see and to examine myriad specimens as I assist MCHC staff to prepare them for exhibition or storage.

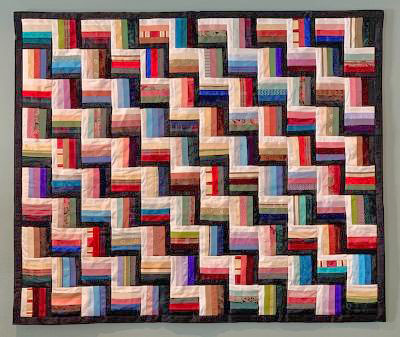

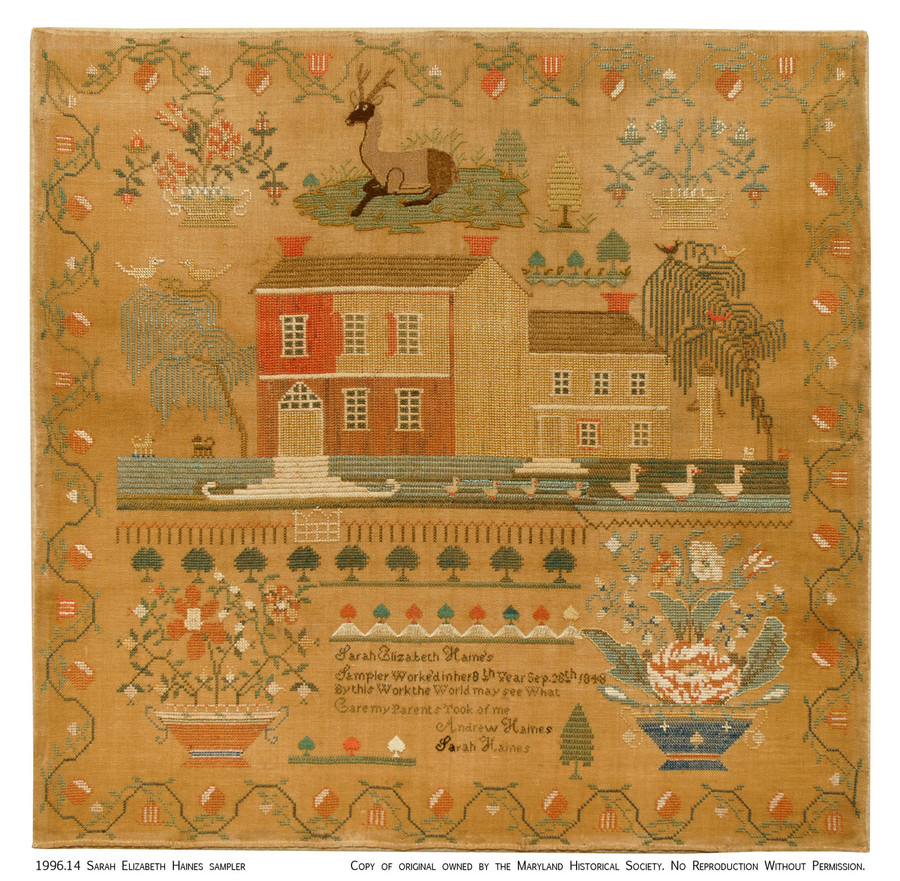

One such discovery (1953.127.21) is the many pieces of an unfinished quilt (Figure 1)—some of which are currently on display as part of the current MCHC exhibition, Wild and Untamed—Dunton’s Discovery of the Baltimore Album Quilts—assembled by Annie G. Dunton (1833-1893) sometime during the 1880s.

A talented seamstress and needleworker, she was an early pupil of the Philadelphia School of Art Embroidery. Her tiny pieces of silk are meticulously cut into 1¼ʺ x 4¼ʺ strips, then five strips are arranged in a dark-to-light color gradation and joined to form a 4¼ʺ square or block. These blocks are arranged horizontal to vertical and attached to each other to form strips (Figure 2) which ultimately would have been sewn together to create the quilt.

Annie G. Dunton’s son, Dr. William Rush Dunton Jr., is known as the father of occupational therapy. He recognized that the repetitive nature of quilting, which also allowed for self-expression and creativity, had a positive effect for those of his patients at Sheppard and Enoch Pratt Hospital in Baltimore who were suffering from mental distress.

These pieces came into the MCHC collection in 1953 with an attached note, presumably by Dr. Dunton: “The pieces of silk in this box were mostly collected by Annie G. Dunton for a ‘Tea Box’ piece of work, parts of which are also in this box and a number, sewed together, are in the chest containing quilts.”* A search for other specimens of “Tea Box” quilts yielded a totally different design utilizing tiny individual squares of fabric rather than strips. It is easy to see why the contemporary quilt experts I consulted put this design in the family of Rail Fence or Split Rail Fence quilts because of its resemblance to the zigzag rail fences once seen in the countryside.

Further research noted that because this design “uses only strips, it was most likely created for more utilitarian purposes,”** meaning it could be cut from fabric scraps rather than special fabrics needed for the decorative whole cloth and applique quilts also popular at this time. Indeed, among the cut pieces are scraps of fabric, some with their intact selvage edges, waiting to be cut into shape. Dr. Dunton mentioned that his mother would sometimes cut up his old school ties to use in her quilts.

Annie’s pieces and her workmanship intrigued and inspired me to create a wall hanging. Although I do not consider myself an expert quilter, I’ve made several simple quilts over the years and am familiar with basic techniques. I knew I wanted to stay close to what Annie had planned, but I also wanted to give it my own signature. Like Annie, I used only silk fabrics. Luckily, my personal “stash” of fabrics contains an extensive assortment of silks left from previous projects, plus some treasured Scalamandré salesman samples. I chose to cut the exact size 1¼ʺ x 4¼ʺ strips from my fabrics and join them into the same five-strip blocks ranging in color from dark to light. The next step was to join the 120 blocks into strips that would then be joined to create my 10-block by 12-block wall hanging.

Figure 4. Construction with the sewing machine.

Figure 3. Preparation for “A Tribute to Annie.”

I marveled at the precision of Annie’s tiny strips, each cut exactly with the weave of the fabric. Today that is an easy achievement with the ready availability of rulers, rotary cutters, and mats (Figure 3). Instead of short 4¼ʺ pieces, modern quilters would use a technique known as strip-piecing and sew together five long 1¼ʺ strips of fabric in the dark to light arrangement, then cut multiple (and identical) 4¼ʺ square blocks. I chose instead, like Annie, to sew the 600 pieces together individually so that each block is unique. Unlike Annie, however, I used a sewing machine (Figure 4) and completed the task in a matter of days rather than the weeks or months it must have taken Annie to precisely hand-stitch each of the ¼ʺ seams making up her blocks.

At about the same time I got started with quilting some 40 years ago, I was introduced to English smocking, an embroidery technique usually associated with little girls’ dresses. I realized at that time there was not room in my life for both, so quilting faded into the background as I spent subsequent years designing, teaching, and writing about English smocking. To give the wall hanging my own stamp, I knew that I had to somehow incorporate smocking and came up with small designs that would fit as a few of the 1¼ʺ x 4¼ʺ strips. I like the texture they add to the piece (Figure 5).

Figure 6. Stitching “in the ditch” to secure the quilt layers.

Figure 7. “A Tribute to Annie.”

It finally came time to put everything together. Traditionally, a quilt is formed of two layers of fabric with an insulating layer of cotton or wool batting sandwiched in between. The verb “to quilt” is the act of stabilizing these layers so that they won’t shift. One method is to “tie” the layers together with individual knotted stitches; another is to secure the layers with multiple rows of stitching in some sort of pattern, either by hand or machine. I chose a third technique known as “stitching in the ditch,” that tiny indentation made on the outer surface when two pieces of fabric are seamed together (Figure 6). By following the pattern of the zigzag lines formed by the blocks, this stitching is virtually invisible and allows the flow of color and design to move without interruption.

Whenever I look at my completed project, now hanging on a wall (Figure 7), I think of Annie G. Dunton. Her inspiration has provided a means to help keep me grounded and occupied during today’s difficult times—just the sort of therapy recognized by her son, Dr. Dunton.

Postscript: I overestimated the number of strips of fabric I would need, so am still busily stitching companion pillow covers and anything else I can think of to use them up!

I would like to thank quilt experts Allison Aller, Mimi Dietrich, and Dawn Ronningen for their insight.

*MCHC 1953.127.21

**www.blog.stitchinheaven.com

The following blog post is a reprint of an essay written by Mark B. Letzer, MCHC President & CEO, that appears in the exhibition catalog, Joshua Johnson: Portraitist of Early American Baltimore, published by the Washington County Museum of Fine Arts. [1]

Post published April 2021.

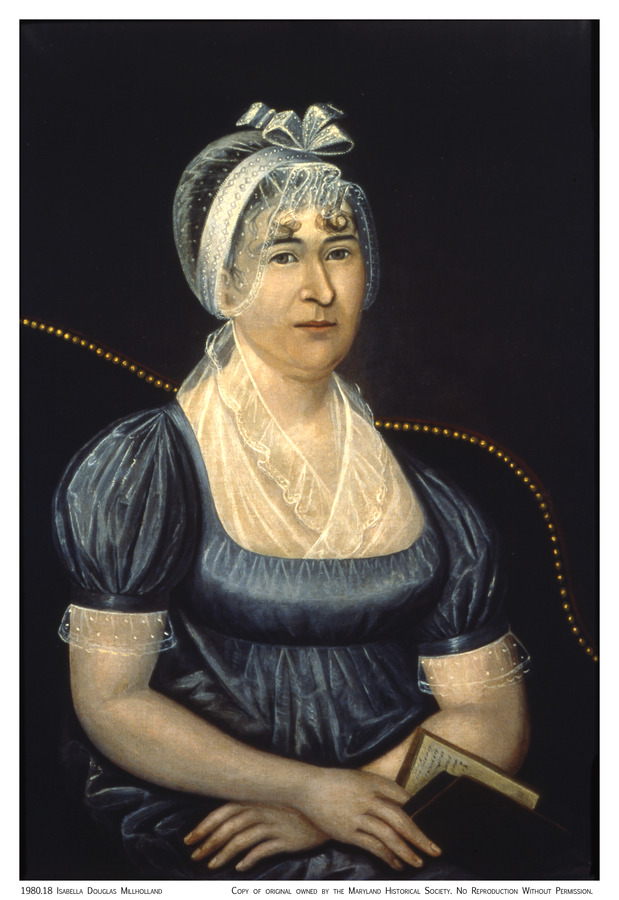

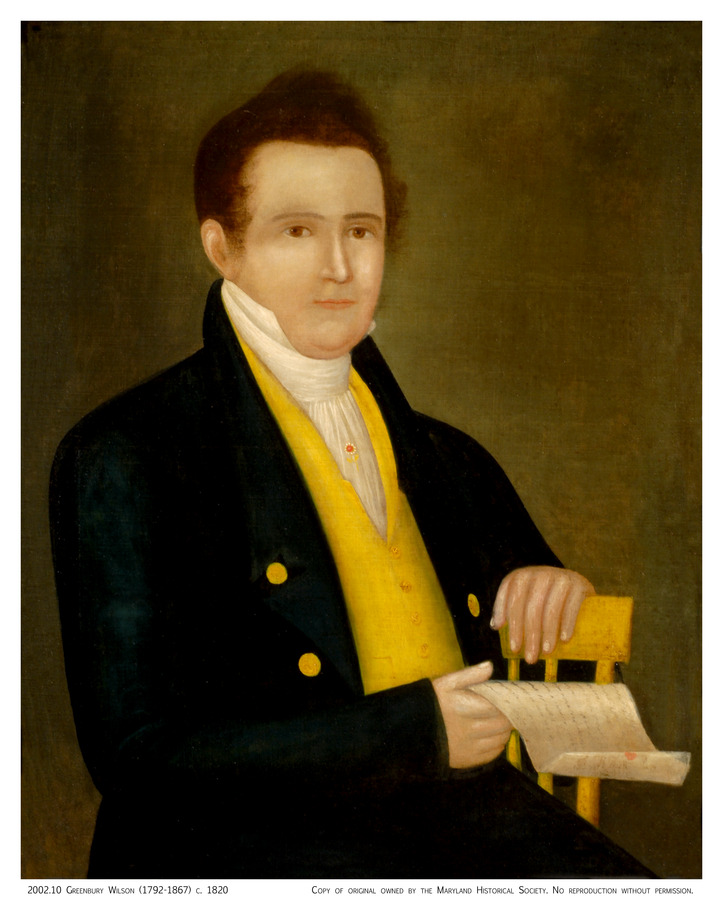

When the Maryland Center for History and Culture (MCHC, formerly the Maryland Historical Society) received a large family portrait in 1920 by Joshua Johnson (ca. 1763–1824), The James McCormick Family (1803–05), this work established a foundation for an important and nationally significant collection of American art. Long recognized as one of the first African American portraitists in the United States, Johnson created canvases of the newly emerging merchant class in Baltimore during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

The Society at that time already understood Johnson’s significance and encouraged the addition of more works by this enigmatic Maryland artist. The story of Johnson is remarkable on several fronts. The most interesting fact of his work in the early Republic was the patronage he received from his patrons living in Baltimore.

Johnson was born to a white father and an enslaved African American woman around 1763. After his manumission in 1782, he set up a painting practice and referred to himself as a “self-taught genius.” [2] More importantly, as a free black man, Johnson painted Marylanders who held enslaved individuals. These ironic circumstances are extremely complex in Johnson’s early Baltimore and warrant further study. A large population of free blacks existed in Baltimore at this time and it was interwoven with the fabric of the community. In post-Revolutionary Baltimore, there was a large population of free blacks that co-existed in this slave-holding society. David Taft Terry’s essay [in the exhibition catalogue, Joshua Johnson: Portraitist of Early American Baltimore, published by the Washington County Museum of Fine Arts] sheds some light on the social conditions related to race at that time. [3]

A doctor and scholar of local history and the fine arts of Maryland, Jacob Hall Pleasants (1873–1957) first examined Johnson in 1939 and published Joshua Johnston, the First American Negro Portrait Painter. [4] Herein he examined Johnson and reattributed portraits that had long been assigned to different artists, from Charles Willson Peale (1741 1827) and Rembrandt Peale (1778–1860) to Charles Peale Polk (1767–1822) and Jeremiah Paul, Jr. (ca. 1775–1820). Once these stylistic differences were examined and evaluated, a larger body of work and new evidence began to emerge and form the nucleus of what we recognize today as a highly significant painter and contributor to the lexicon of American art. Pleasants wrote in the foreword of the catalogue for the first exhibition of Joshua Johnson’s portraits held at the Peale Museum in 1948: “A NEBULOUS FIGURE, A Negro painter of considerable ability with a style primarily his own.” [5]

In 1987, the exhibition Joshua Johnson, Freeman and Early American Portrait Painter opened at the Maryland Historical Society in Baltimore, traveled to the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Center in Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia, then went to the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, and finally was shown at the branch of the former Whitney in Stamford, Connecticut, finalizing its tour in 1988. [6] This landmark exhibition gathered the 83 known works known to have been painted by Johnson or attributed to him and it was accompanied by a catalogue raisonné. Much has been written regarding Johnson and his reliance on, as well as his possible exposure to, the Peale family of painters. His style has been compared particularly to that of Peale Polk and this resemblance was emphasized in the seminal exhibition of 1987–88. Comparisons between his work and especially that of Peale Polk showed similarities that are certainly present in Johnson’s stylistic arrangements and could indicate such an influence. Whether Johnson was ever exposed to the Peale family of painters or Peale Polk directly we may never know, but he must at the very least have seen their works. In previous scholarship, it was still widely believed at this time that Johnson had been a protégé of the Peales.

Johnson’s painting, Mrs. John Moale (Ellin North) (ca. 1798 1800), was created very close to the time Mrs. Moale also sat for a portrait by Rembrandt Peale (ca. 1798–1800).

It is likely that Johnson would have been exposed to this work as well as other portraits in the collections of his clients. It is also significant to note that we do not know whether Johnson visited his sitters at their homes to paint them or they sat for him at his studio. In his 1798 advertisement, the artist stated that he “respectfully solicits encouragement… Apply at his House, in the Alley leading from Charles to Hanover Street , back of Sears’s Tavern.” [7] Did the clients apply and sit at his house and did it serve as his studio? As with many art historical subjects, we have few answers to the many questions regarding the set-up and the props that might have been Johnson’s.