A Major Booster Event for Baltimore

Post published September 29, 2022

One hundred eight years ago this fall, the city of Baltimore played host to the Star-Spangled Banner Centennial Celebration. This was a week-long commemoration ostensibly aimed at promoting patriotism and respect for the American flag but importantly—and perhaps less known—an event also aimed at bolstering the image of the city of Baltimore. In this blog post, Emma Z. Rothberg, PhD, Maryland Center for History and Culture’s Lord Baltimore Fellow for 2019/2020, explores the 1914 celebration and her experience diving into primary resource materials within MCHC’s H. Furlong Baldwin Library.

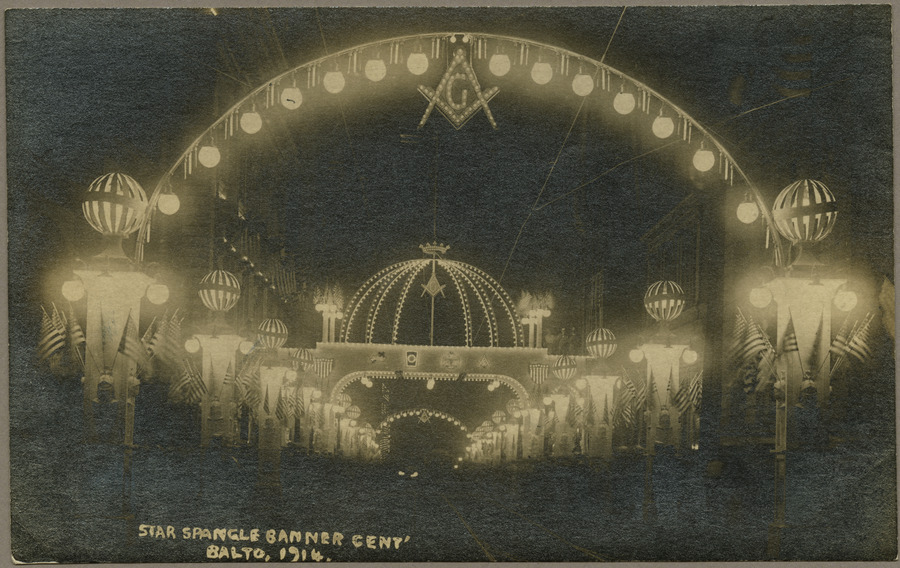

Baltimore was abuzz on Monday, September 7, 1914. The day before, Baltimoreans had gathered in churches to hear sermons on patriotism, seen a concert in Druid Hill, watched boat races on the Patapsco River, and reveled as their city lit up in a fantastical light show. This morning, however, there was to be a grand parade through central Baltimore. The people who lined the streets expectantly for the 10 am start time were excited to see the floats and marching organizations representing Baltimore’s industrial and civic landscape. Some may have wondered which float in the industrial section of the parade would win First Prize ($250) and best decoration ($250); others were interested in cheering on marching laborers, athletic clubs, or—perhaps—the marching group of female suffragists. The waiting spectators were abuzz with anticipation.

From September 6 to 13, 1914, Baltimore was the site of a spectacular celebration honoring the 100th anniversary of the Battle of Baltimore and the penning of “Star-Spangled Banner” by Francis Scott Key. Baltimore’s Mayor James H. Preston first suggested the centennial celebration in 1913. He hoped the celebration of an event of such national importance would instill patriotism and respect for the American flag in the nation.[1] To that end, the Star-Spangled Banner Centennial Celebration week was full of monument and historic plaque dedications, historical exhibitions and speeches at various institutions across the city, a recreation of the bombardment of Fort McHenry (in fireworks), and the arrival of historic ships in Baltimore’s harbor. Military and naval organizations received their own day to parade as did the Star-Spangled Banner itself (President Woodrow Wilson, members of his cabinet, governors, 100 representatives of each state in the union in 1814, and Civil War veterans all escorted the flag during the Star-Spangled Banner Legion parade on September 12).[2]

But the Star-Spangled Banner Centennial was much more than a celebration of this historic moment and of the song that became the national anthem in 1931. The celebration was a major booster event for Baltimore. It is this aspect of the celebration that struck me the most as I read through the H. Furlong Baldwin Library‘s archival holdings of the event. Why was an economic booster event so important in this moment? And why connect it, or—if I was less generous—mask it, using a national event? The most likely answer is that the Baltimore of 1914 was a city still in recovery.

On the morning of Sunday, February 7, 1904, a fire broke out on the fourth floor of the six-story John E. Hurst & Co. wholesale dry goods store on the southwest corner of Hopkins Place and German Street (20 Hopkins Place). As firefighters responded, a strong wind carried the flames and embers across the business district. The exceedingly hot flames were too much for the firefighters’ hoses, and they spread quickly throughout the non-fireproof buildings downtown. Eventually, the fire burned roughly 140 acres, or 80 city blocks, at the heart of the waterfront and business district to the ground; the “burnt district” lay in ashes.[3]

The fire was devastating not only because of the physical destruction and emotional toll it took on Baltimore’s residents, but because it decimated one of Baltimore boosters’ main selling points—economic opportunity in the city. Baltimore had been combating its image as the “little sister” of larger American cities since the end of the nineteenth century. During the Baltimore Sesquicentennial in 1880, organizers too used Baltimore’s businesses to boost the city and combat its image as a “branch office town.”[4] Baltimore’s business and political leaders wanted to market the city as a solid and safe investment, a city ready to be an economic leader.[5] The destruction of the business district in 1904 was a setback to this decades’ long sales pitch, but Baltimore’s economic and political leaders were ready to dust themselves off (in some cases literally, if they had been too close to the ash) and get back to work.

The recovery was slow and expensive but also successful. Mayor McLane appointed a 63-member Citizens Emergency Committee to devise a rebuilding program for the “burnt district”; its chairman was a local industrialist, and the commission was made up of Baltimore’s elites. Yet the fire was also a catalyst for urban development and civic engagement—streets were widened and repaved, public spaces rebuilt, and a sewer system constructed. In September 1906, a year before the rebuilding was fully complete, the week-long Greater Baltimore Jubilee and Exposition celebrated the city’s recovery.[6] But 1914 was an opportunity to a put a national spotlight on this recovery and the economic promise Baltimore once again represented.

Now someone could read the documents of the Star-Spangled Banner Centennial and think, “what an over-the-top celebration.” I certainly expected that when I first began reading the meeting minutes of the Commission planning the celebration. But as I looked through the minutes and the programs, I started to notice a pattern.

Because of their symbolic resonance, I focused my search on the parades that served as the main event each day of the week-long celebration. Parades were part of a time-honored tradition for marking and celebrating civic achievements and events. Parades were a common feature of Independence Day celebrations and the opening of civic infrastructure projects—such as canals, bridges, and buildings—across the country. Fire companies, veterans, and political and fraternal organizations also all frequently turned to parades as a way of showcasing and promoting themselves. The Star-Spangled Banner Centennial organizers must have been aware of these parading traditions and a parade’s ability to create and instill a collective identity amongst participants and observers. Baltimore already had its own substantial parading tradition as a main feature of large-scale civic events.

Because of their symbolic resonance, I focused my search on the parades that served as the main event each day of the week-long celebration. Parades were part of a time-honored tradition for marking and celebrating civic achievements and events. Parades were a common feature of Independence Day celebrations and the opening of civic infrastructure projects—such as canals, bridges, and buildings—across the country. Fire companies, veterans, and political and fraternal organizations also all frequently turned to parades as a way of showcasing and promoting themselves. The Star-Spangled Banner Centennial organizers must have been aware of these parading traditions and a parade’s ability to create and instill a collective identity amongst participants and observers. Baltimore already had its own substantial parading tradition as a main feature of large-scale civic events.

The pattern I noticed was the focus on industrialism. Two of the week’s parades—Monday’s Industrial and Civic Parade and Thursday’s 8 pm Historical Pageant parade—highlighted the theme. The industrial section led off Monday’s parade; included in the section were floats for both national (like Rockefeller’s Standard Oil) and local companies (like the Maryland Ice Cream Co.). The fact that industry was the first section of the first parade of the week meant that organizers felt industrialism was the most important theme of the week. Symbolically, that struck me as odd given the Centennial was of an historic event. Similarly, the Historical Pageant was split into two parts: the First Division was the “Events of 1814,” and the Second Division was “One Hundred Years of Progress.” The “progress” visualized by the Historical Pageant’s second division was an industrial one. Floats included in this section were dedicated to the Industries of Maryland, Commerce by the Canal, the Laying of the Cornerstone of the B&O, and the Rebuilding of Baltimore (after the Great Fire of 1904 float). Not included in this progress section was the end of slavery in Maryland, the expansion of civil and political rights, or the question of the vote—a particularly interesting omission to me given that there was a Suffrage Section in the civic division of the Industrial and Civic Parade on Monday. But maybe I shouldn’t have been too surprised; Maryland was a border state during the Civil War and retained slavery until the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment. Maryland’s General Assembly had been attempting to limit the franchise for much of the twentieth century to white men only.[7]

In a letter printed on Mayor’s Office letterhead included at the front of the National Star-Spangled Banner Centennial Official Program and the Story of Baltimore (1914), published by the National Star-Spangled Banner Centennial Commission, Mayor Preston wrote “To Our Visitors”:

The people of Baltimore join with you in paying patriotic tribute to the Flag of our country, and to the heroes, the shedding of whose blood has made that flag so sacred. We want you to know our city—big, enterprising, progressive, success; we want you to know our people—hospitable, courteous, patriotic, chivalrous; we want you to know our history—important, creditable, nation-wide in its influence.[8]

The Star-Spangled Banner Centennial Celebration is an example of the ways in which patriotism and capitalism were, in many ways, intertwined in the United States. What the organization of the parades posited was that to be patriotic was to be a good investor or consumer. Buy American! Or, more specifically, buy (into) Baltimore! Based on the descriptions and the photographs of the event, it was a dynamic sales pitch.

Emma Z. Rothberg received her PhD in History from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 2022, where her research focused on urban, cultural, and gender history in the 19th and early 20th century United States. Her dissertation examined the cultural practices of urban democracy and identity in American cities at the turn of the 20th century. Dr. Rothberg is now the Associate Educator, Digital Learning & Innovation at the National Women’s History Museum. Originally from New York City, she received her BA from Wesleyan University and MA from UNC-Chapel Hill.

[1] “Series Description, Information on BRG15-(National Star Spangled Banner Centennial Commission),” Baltimore City Archives, accessed September 29, 2022, http://guide.msa.maryland.gov/pages/series.aspx?ID=BRG15

[2] National Star-Spangled Banner Centennial Commission, “National Star-Spangled Banner Centennial, Baltimore, Maryland, September 6 to 14, 1914. Official Program and the Story of Baltimore” (1914), 90-113, https://archive.org/details/nationalstarspan01nati/page/n13/mode/2up

[3] Matthew Crenson, Baltimore: A Political History (Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, 2017), 333. For more see Peter B. Peterson, The Great Baltimore Fire (Baltimore: Maryland Historical Society, 2004).

[4] Crenson, 313.

[5] For more, see Emma Z. Rothberg, “‘The Wealth and Glory of the City’: Displays of Power in Baltimore’s Sesquicentennial,” Maryland Historical Magazine 115, no. 2 (Spring/Summer, Fall/Winter 2020), 63–99.

[6] Crenson, 333.

[7] By 1911 there had been a series of drafted amendments meant to strip Black men of the franchise, including: the 1904 Poe Amendment (defeated by referendum); 1909 Straus Amendment (defeated by referendum); the Grandfather Clause in the Annapolis city code (successfully stripped Black men of the vote in the city until the Supreme Court declared it unconstitutional in 1915); and the 1911 Diggs Amendment (defeated by referendum). In terms of women’s right to vote, Maryland women received it when the 19th Amendment was ratified in 1920. Maryland itself had rejected the amendment in 1920 and would not ratify the 19th Amendment until 1941.

[8] National Star-Spangled Banner Centennial Commission, “National Star-Spangled Banner Centennial, Baltimore, Maryland, September 6 to 14, 1914. Official Program and the Story of Baltimore” (1914), 9, https://archive.org/details/nationalstarspan01nati/page/n13/mode/2up