Double, Double Toil and Trouble: Witchcraft in Maryland

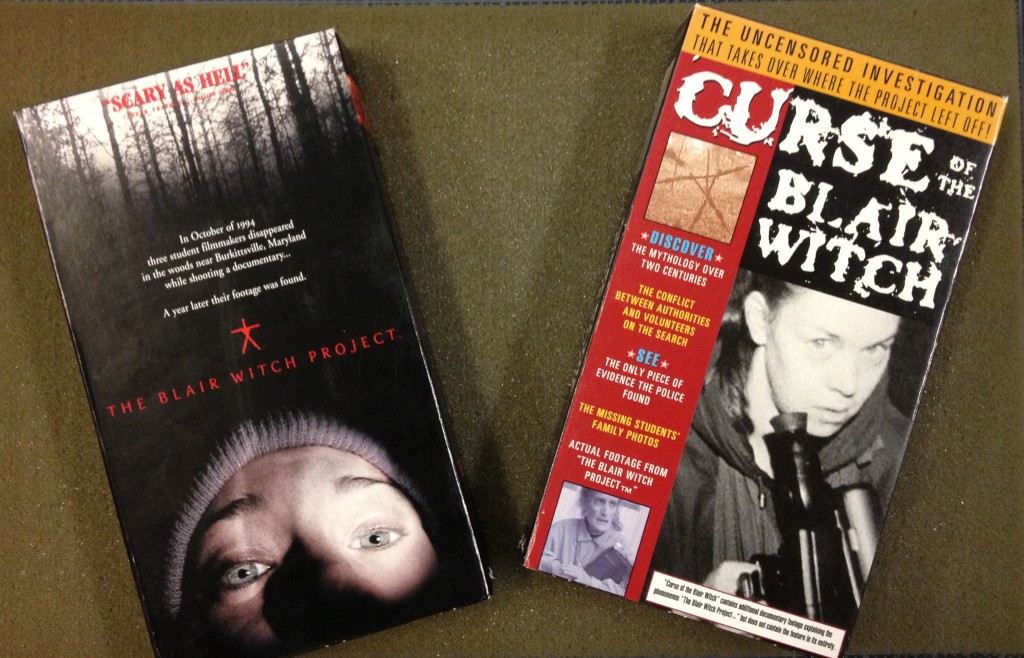

Maryland’s most famous witch: The Blair Witch… on VHS. The Blair Witch Project & The Curse of the Blair Witch, Moving Image Collection, MdHS.

The perilous waters of the Atlantic Ocean condemned Maryland’s first witch. The Charity of London set sail for the New World in 1654 from England with her crew and small group of passengers looking to settle the new colony. Mary Lee was one such passenger, but she never set foot on Maryland’s shores.

Travelers knew that the trip across the ocean was a dangerous endeavor, but this crossing proved particularly hazardous. Choppy seas and violent winds plagued the Charity of London’s journey from the start. An attempt to make land in Bermuda had failed due to crosswinds, “and the Ship grew daily more leaky almost to desperation and the Chiefe Seamen often declared their Resolution of Leaving her if an opportunity offered it Self….”(1) The passengers and crew grew more agitated as the ship weakened and the weather refused to yield. Rumor took hold amongst the crew that a witch had conjured the storms. Father Francis Fitzherbert, a Jesuit traveling to Maryland aboard the Charity, recalled the sailors reasoning that the foul weather “was not on account of the violence of the ship or atmosphere, but the malevolence of witches.”(2)

The sailors decided that Mary Lee was that witch and petitioned the captain to put the woman on trial. The storms delayed the proceedings, so two seamen decided to take matters into their own hands. They seized Lee and searched her body for the Devil’s markings. They found a damning mark—a protruding teat from which the Devil and his familiars could supposedly feed—a well-known sign of witchcraft at the time. She was subsequently hanged and her corpse and belongings dumped overboard. The Charity landed in St. Mary’s City, Maryland worse for wear but in one piece and without a witch.

Accounts of witchcraft, such as the story of Mary Lee, were common in the 17th century. An anti-witch hysteria had recently swept across Europe, and the English crown enacted several statutes criminalizing sorcery. The Devil and black magic were real and present dangers in everyday life, and witches could summon that dark power with the mere mumbling of a curse.

These old world superstitions and religious convictions immigrated with the colonists. Witchcraft left an indelible mark on Maryland’s early court cases and became embedded in local folklore. Maryland never saw witch hunts on the scale of Salem, Massachusetts, but men and women alike were accused and convicted of witchcraft. Sources vary on the exact number of prosecutions, but only about 12 people were brought to trial over a hundred year period, compared to 19 executed in Salem in 1692 alone.

![Text from Violl's trial documents. Notice that she was "seduced by the devill wickedly & diabolically...." "Witchcraft, trials for, in Maryland. [manuscript] : Document, 1702/3 1712," MS 2018, MdHs](https://www.mdhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/violl-300x225.jpg)

Text from Violl’s trial documents. Notice that she was “seduced by the devill wickedly & diabolically….” “Witchcraft, trials for, in Maryland. [manuscript] : Document, 1702/3 1712,” MS 2018, MdHS. (Click to enlarge.)

Accusations of witchcraft often arose from town disputes. These cases typically unfolded in the same manner. An argument would erupt between neighbors, and shortly thereafter one of the begrudged would fall mysteriously ill or his or her chickens would be suspiciously killed one night. Such is the story of the last witch ever tried in Maryland—Virtue Violl of Talbot County. Violl found herself on trial in 1715 in Annapolis after a quarrel with a fellow spinster, Elinor Moore. Moore accused Violl of cursing her tongue, which rendered her unable to speak. The jury however was not convinced of her guilt and acquitted her of all charges. Falsely accused witches were not without recompense. They could sue for defamation of character, and a few were awarded damages, which was often a few hundred pounds of tobacco.

While few witches met their untimely end in Maryland, local folklore is rife with legends of evil sorceresses and superstitious antidotes for bewitchments. Glass bottles containing sharp objects, such as pins, and urine were buried under the entrance of a home to prevent a witch from entering the property or cursing its inhabitants. These so-called witch bottles have been unearthed in archaeological digs across the state. The urine “was the most important ingredient in witch bottles, as it is the agent with which the spell is turned back upon the witch.”(4) They were also buried upside down to reverse the black magic. Another trick to keep witches at bay was to place a broomstick across the threshold of a home’s entrance. A witch supposedly could not exit the dwelling without counting the broom’s bristles, thus revealing his or her identity.

Many tales of witches have surfaced over the years. Each county seems to have its own wicked woman who tortured the innocent townspeople and met a gruesome death for it. The legend of Moll Dyer out of Leonardtown in St. Mary’s County has endured the centuries. The details of Dyer’s story have changed and been embellished over time, but all accounts agree that in February of 1697 she was chased from her home by torch-bearing townsfolk. She fled into the woods where she froze to death after cursing the town. Dyer died kneeling upon a rock, which still bears the imprint of her hands and knees and can be viewed in front of Leondardtown’s circuit courthouse.

The dreaded book on display at MdHS. “The Blair Witch Cult,” blairwitch.com

No story about witchcraft in Maryland would be complete without mentioning the Blair Witch. The Blair Witch, Elly Kedward, terrorized the town of Blair, now Burkittsville, during the late 1700’s and was executed for her crimes. The following year, her accusers as well as many of the town’s children disappeared without explanation, and as a result the town was abandoned. Other weird happenings continue to plague the area and are attributed to the restless spirit of Kedward. The frightening occurrences culminated with the disappearance of three student filmmakers who visited the town to investigate the haunting. The footage found from their exploit was released as the film, The Blair Witch Project.

The legend of Kedward and the associated murders was, of course, pure fabrication. The Blair Witch Project holds a special place in our hearts here at the library, because of a connection, albeit false, to our collection. The film claimed that The Blair Witch Cult, a book published in 1809 which recounted the tale of the town doomed by Kedward’s curse, was held at MdHS and even featured in a exhibit. The movie’s website points out that the book was returned to private hands before the film was released but that didn’t stop curious moviegoers from inquiring about the dreaded book. Our wonderful reference librarian, Francis O’Neill, fielded phone calls about the fictitious tome from all over the country and even from as far away as Belarus for many years after the movie came out. Each time, he would kindly and dutifully explain that book was entirely made up for the movie and never resided in our library. The movie itself is now a part of our growing Maryland-related film collection, along the films of John Waters and other local filmmakers. But please for Mr. O’Neill’s sanity, please don’t call about the Blair Witch! (Lara Westwood)

Sources and Further Reading:

(1):Alison Games, Witchcraft in Early North America (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2010) 133.

(2): William H. Cooke, “The Maryland Witch Trials.”

(3): Francis Neal Parke, “Witchcraft in Maryland,” Maryland Historical Magazine 31 (1936):283.

(4):Rebecca Morehouse, “Witch Bottle.”

“Witchcraft, trials for, in Maryland. [manuscript] : Document, 1702/3 1712,” MS 2018, MdHS.