Lost City: Baltimore’s Vibrant Automobile Show Rooms

Nash Motors Company Dealer – Martin Brothers, 2300 N. Monroe Street, Ca. 1949,Hughes Company Studio Photograph Collection, PP30-1083-48-03, MdHS.

In early 1900s Baltimore, Mt. Royal Avenue looked quite different from the land originally developed in 1881 carved from portions of Oliver and Johns Streets. The advent of the automobile began to change the face of America and Baltimore. Beginning in 1899 automobile showrooms began to sprout up on Mt.Royal Avenue. Brands like Locomobile, Peerless, Lozier, and Packard, along with the more familiar Ford and Chevrolet brands and many more long gone, lined both sides of the street, east and west for several blocks.

Decades later these dealerships began moving north as the demographics of Baltimore changed and the North Avenue corridor became the next stepping stone. The post-WWII years saw another shift as dealerships began to migrate to more spacious areas in Baltimore County.

In those early days, from 1300 W. Mt.Royal to McMechen Street auto dealers proliferated. Male customers attired in suits, ties, and hats accompanied by women wearing fashionable dresses shopped for their first car. The automobile became a status symbol as the Studebaker, Chandler, Lozier, Pope Hartford, Reo, Pierce Arrow, Thomas Flyer, Steven-Duryea came on the market. And they were expensive—the Lozier cost as much as $5,000 in 1912 (steel workers, in 1912, were making $630 a year and public school teachers $507). Today the Lozier is a highly prized antique automobile. In 2013 a 1911 Lozier, Model 51, sold at a Sotheby Auction for $1,100,000.

Carl Spoerer’s Sons Company Automobile Repairing, South Carey Street, July 1929, Baltimore City Life Museum Photograph Collection, MC7410, MdHS.

Baltimore had its own home-grown automobile industry. In 1890,Carl Spoerer made wagons and carriages at 400-402 South Fremont Avenue. His sons, Charles and Jacob, seeing a declining market for carriages and recognizing the automobile as the future, decided to expand their factory on Fremont Ave and get into the car business. The Carl Spoerer’s Sons Company was formed after Carl died in 1899.

Needing more space, the brothers moved to a larger building at 901-909 South Carey Street in 1907, and they took on two partners, John F. and B.J. Reus. From 1907 to 1914, they built the Spoerer automobile which was available in several different styles; a roadster, a five and seven passenger touring car, a limousine and a landaulet (similar to a limo but with the passenger seat covered by a convertible top). The Spoerer Model B sold for about $3,000 in 1912.

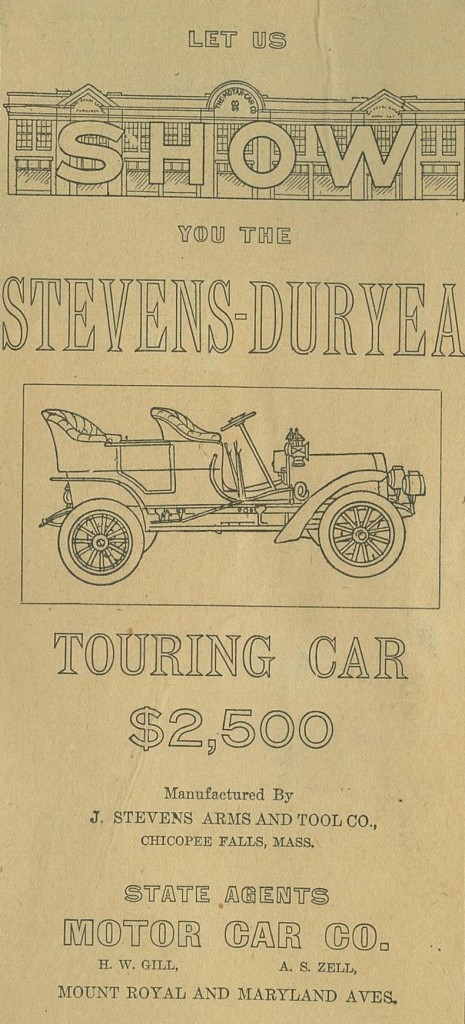

The Motor Car Company of Baltimore’s Advertisement for the Stevens-Duryea Touring Car, ca 1908, MS 1060, MdHS (Reference photo).

In their new South Carey Street factory, they branched out and started making light commercial vehicles. Their delivery wagon weighed 1500 pounds, had a 30-horsepower engine and a four-speed transmission with one reverse gear. As competition grew stronger, the company decided to get out of the vehicle manufacturing business and began selling tires and other automotive accessories. Carl Spoerer’s Sons went out of business in 1934.

In 1905, H.W. Gill and A.S. Zell opened the Motor Car Company at 18-24 W. Mt. Royal Avenue where they built a garage and showroom selling Overland and Maxwell automobiles. After the demise of these two auto manufacturers in the mid-1920s, the company switched to Studebaker. The Motor Car Company survived until 1960. In turn it became Pat Hays Buick, and in 1970 the University of Baltimore bought the site and demolished the building.

The site where Gill and Zell opened their car company at the corner of Mt. Royal and Maryland Avenue has a colorful history. In 1889 a circular framed structure, clad with metal was erected to house a Cyclorama of the Battle of Gettysburg and for the following 12 years hosted a variety of spectacles including a roller rink and a bike riding school. Frank Bostock, an internationally renowned animal trainer opened a zoo at the location in 1900 but on January 30,1901 the building burned down trapping all of the animals in it.

Later stories abounded that Bostock hanged an unruly elephant, on the way to Baltimore from New York in May 1900. But the situation surrounding that story was more complicated. In one boxcar, two elephants named Sport and Jolly were rough-housing and Sport, hit the side door of the box car door so hard he fell out, screaming. The railcar was stopped, but Sport was unable to get up on his own—a crane lifted him back on the railcar and the train continued on to Baltimore. Sport was so severely injured he had to be put out of his misery, and according to the local Humane Society, the most humane way to do so was to hang him. Strangely enough, Sport’s partner Jolly died of heart failure the day before the hanging, apparently depressed over her partner’s tragedy (You can read an in-depth account, The Death of Sport, in a previous underbelly post).

Nash Motors Company Dealer, Unidentified dealership, interior, Ca. 1949, Hughes Company Studio Photograph Collection, PP30-1083-48-08, MdHS.

Another site on Mt.Royal, one at the corner of McMechen Street, also has a long and varied history. The Frick family, a big name in street railways controlled the land at this corner from 1880 to 1890. It was used by Park Railway, Baltimore-Peabody Heights and Waverly Railroad. In 1892 Frick sold the land to North Baltimore Railway and to the Baltimore Traction Company. Shortly thereafter a fire leveled their wooden stable. In 1897 the property was sold to Baltimore Consolidated Railway which merged with Baltimore Traction, which, in turn merged with United Railway & Electric Company. These premises were vacated in 1924 and Howe & Jones, a Chevrolet dealer remained there from 1926-1930. The building served as a drill hall for the 5th Regiment National Guard from 1933-34, when it became an auto dealer once again—Bob Fleigh Studebaker. MICA now occupies two corners and an apartment house is built on the third.

At 16-18 W. Mt. Royal, site of the former United States Truck Agency, Union Motor Car moved into this location, according to the January 1919 edition of Motor World. At 26 W. Mt. Royal, Overland cars were sold from 1919 to 1928. Today this site is the University of Baltimore’s Gordon Plaza.

Monumental Motor Car Company did business at 21 W.Mt.Royal. When they built their showroom in 1916, it was a two-story affair with post and beam construction and a Tudor Revival exterior. The interior design was influenced by the Arts and Crafts movement with modern and historical details throughout. Monumental sold the Kissell known as the “KissellKar” and a sportier model called the Kissell Goldbug a favorite of celebrities such as Jack Dempsey, Douglas Fairbanks, Al Jolson, Greta Garbo and Eddie Duchin. Production of the Kissell lasted from 1907 to 1931. The building was later occupied by the Odorite Company. The Monumental Motor Car showroom site persevered until 2004 when University of Baltimore demolished the building in spite of strong objections from local and state preservationists and built a new student center on the site.

Another auto show room of historic significance is still located at 1370 North Avenue: the Brooks-Price Buick dealer, built in 1939. The U.S. Department of Interior describes the building as “a deceptively large structure that stretches in a pie shaped mass filling the entire block from north to south…representing the classic style of Albert Kahn.” Architect Kahn had built a prototype Art Deco building for General Motors at the 1933 Century of Progress Exhibition in Chicago in 1933. The Brooks-Price showroom represented that Art Deco style of the period and the post depression era.

The property at 107-113 W.Mt. Royal changed hands several times. In 1908 Baltimore Buggy Top built on this site. In 1921 Neill Buick opened shop and vacated it ten years later where it remained vacant until 1934 when the building was demolished. City Chevrolet used the vacant lot for storage until their business closed in 1960. The property added six more lots (101-106) and W. Bell, a merchandise distributor conducted business there until the property was sold and the building demolished. The site’s current building is occupied by the Associated Jewish Charities.

Buicks were sold at Kelly Buick at the corner of Mt.Royal and Charles Street in 1937. Customers looking for something classier went to Zell Motors across the street at 11-19 E. Mt Royal where they had been selling Packards for many years.

Mr. Arthur Stanley Zell (1880-1935) built a beautiful three story Hispano-Gothic showroom in 1920 at this location and, fortunately, his building survived over the years and is now called the Towne Building. This building has gone through several owners since it was the Packard automobile showroom and was being offered for sale in 2015 for $3.5 million. The exterior of this unique structure is much like it was as the Packard showroom, except that the large glass showroom windows on each side of the stone columns now have stone panel infills. Zell’s sister, Gertude Carroll Zell (1888-1968), was married to Baltimore architect Theodore Wells Pietsch (1869-1930)and was reported to be the first woman to drive a car in Maryland, most likely a Packard.

Many of the automobile dealers sold brands that no longer exist. The Poehlmann Automobile Company located at 106 West Mt.Royal Avenue sold Chandlers. The “Light Weight Six” sold for $1785 in 1919. The Chandler Motor Car Company had a high of 20,000 cars sold nationwide before ending production. In 1927,sales tapered off, a large debt incurred and the company was sold to the Hupp Motor Co., in 1929.

Reus Brothers Company storefront, 150 West Mount Royal Avenue, July 1929, Baltimore City Life Museum Photograph Collection, MC7409, MdHS.

Southern Auto, located at 1300 Mt.Royal Avenue from 1900 to 1915, sold the Lozier and Pope Hartford luxury cars. And the list could go on and on: Reus Brothers Company, 150 W. Mt. Royal; Everett Auto, 1200 W.Mt.Royal; Nash Motor Car (1919), 124-126 W.Mt.Royal; Lambert Motor Car (1920), Mt.Royal and Maryland; Peerless, Thomas Flyer, Stanley, Stevens, Duryea (1908) and Overland (1919-1928), 26 Mt. Royal; White Motor Company (1913), Mt.Royal and Guilford Avenue; Fidelity Motors-Chrysler (1920), Mt. Royal & Cathedral Street.

Today, automobiles are more or less commodities, and are available to nearly all. Changing technologies and demographics have altered Baltimore in any number of ways. In the early days of the 20th Century, buying an automobile was a very special experience available to the few who could afford and enjoy that experience. (Sidney Levy)

Sidney Levy is a volunteer in the Special Collections Department at the Maryland Historical Society.

Nash Motors Company Dealer, Unidentified dealership, Ca. 1949,

Hughes Company Studio Photograph Collection, PP30-1083-48-04, MdHS.