Lost City: Local Taverns and Big Breweries

Nationa Bohemian kegs, National Brewing Company, O’Donnell and Conkling Street, 1946, A. Aubrey Bodine Collection, B815 G, MdHS.

Back in the days when Baltimore was a manufacturing center, neighborhood bars were gathering places for the blue collar workers that worked in the industries. Their thirsts were quenched by the local breweries that produced beer for working men and women and even some high quality brews.

Many of these neighborhood taverns were destroyed in the Great Baltimore Fire of 1904 with many more going out of business during Prohibition. A large number of the local breweries also felt the impact of the prohibition era and closed their doors. The impact of the loss of the manufacturing industry in Baltimore changed the nature of neighborhood bars and the course of urban redevelopment in the mid-20th century contributed to more bar closings.

In 1783, settlers from Germany formed the German Society of Maryland to promote their language and culture in Baltimore. They also built breweries and beer gardens to quench their thirst for beer styled after their home brews. By 1850, Baltimore’s population was just over 169,000, with over 20,000 immigrants from Germany, representing slightly less than a 12 percent of the population. By 1865 this percentage increased to 25 percent and in 1890 the population of German-born Baltimoreans increased to 41,930, but because of a surge in the overall city population to 365,862, they comprised about 11 percent of all residents. Breweries, beer gardens, and taverns spread through Baltimore.

There were corner taverns in most working class neighborhoods—gathering places where workers might stop in on the way home to have a quick beer and exchange local news and gossip. On weekends, they might send their grade-school son “up the corner” with a small tin pail to bring home some draft beer for lunch or dinner. Taverns were plentiful along Wilkens Avenue, a German-American enclave, with countless others on Paca Street, in Southwest Baltimore and down by the waterfront docks.

The Wartime Prohibition Act of November 18, 1918, passed following the signing of the World War I Armistice ten days earlier, banned the manufacture of beer and wine if the alcohol content exceeded 2.75 percent—a major hurdle for the local bars and breweries. It differed from the 18th Amendment that created national prohibition which banned the manufacture, importation, sale and transport of alcoholic beverages. The 18th Amendment was ratified on October 28, 1919 by every state, except Connecticut and Rhode Island. The following year, Congress passed the Volstead Act to enforce the Amendment which took effect January 16, 1920.

Bootlegging and crossing the border into Canada for whiskey became ways of circumventing Prohibition. A popular ditty at the time was:

Four and twenty Yankees, feeling very dry

Went across the border to get a drink of rye

When the rye was opened, the Yankees began to sing

“God bless America, but God save the King” (1)

Whiskey had been widely prescribed by physicians at the time and it was reported that from 1921 to 1930, doctors earned about $40 million from issuing these kinds of prescriptions.(2)

Al and Ann’s Tavern, former and future site of the Horse You Came in On, 1963.

1626-1628 Thames Street, 1963, Baltimore Heritage Inc. Collection, 1963.1.847, MdHS.

Although prohibition led to the closing of a number of Baltimore’s historic bars, a few 18th century taverns have managed to survive into the present day, most notably in Fells Point. With its proximity to the waterfront community in the 1700s, Fells Point served sailors and seafarers plenty of alcohol from the bars proliferating there. Located within the Fells Point Historic District at 1626 Thames Street is what is presently called The Horse You Came in On Saloon, Opened in 1775 and operated continuously ever since, even through Prohibition, it is the only bar in Maryland that can lay claim to that title. It is also known locally as the last bar Edgar Allen Poe visited before his mysterious death in October 1849. When purchased by Howard Gerber 1972, the tavern was named Al and Ann’s but Mr. Gerber thought the “Horse” appellation more appropriate. Current owners, Eric Mathias and Loannis and Spiros Korolgos have continued the Western theme.

Site of the Waterfront Hotel.

1710 Thames Street, 1963, Baltimore Heritage Inc. Collection, 1963.1.855, MdHS.

Just down the street, at 1701 Thames Street is the Waterfront Hotel, built in 1771 as a residence for a Thomas Long. Ten years later it was converted to a hotel by Cumberland Dugan (1747–1836), an Irish immigrant from Londonderry, who welcomed his guests by placing an open clam on their pillow. Edgar Allen Poe was a frequent guest and had a few drinks at the hotel’s bar. Later, detective story writer Dashiell Hammett (1894–1961), imbibed at the bar. Born in St. Mary’s county, Hammett gained the reputation as one of America’s greatest mystery writers, having written The Maltese Falcon and created The Thin Man “Nick and Nora Charles” series—both went on to become smash Hollywood movies. The Waterfront continues to serve food and drink, although today it’s a hotel in name only.

Along with most of the taverns, the big breweries also disappeared, replaced by national/international brands and industry consolidations. Old timers will recall the American Brewery, Gunther Brewery, National Bohemian, The John F. Wiessner & Sons Brewery, and Globe Brewery. In all, over 100 breweries have come and gone in Baltimore.

Lost Taverns

Kaminsky’s Inn, corner of Mercer and Grant Street, ca. 1875, Baltimore City Life Museum Collection, CC2821, MdHS.

Although the Horse You Came in On may have the title of the longest continuously operated tavern in Baltimore, Kaminsky’s Inn, built in 1750 at the northwest corner of Mercer and Grant Streets, may have been the oldest tavern in the city. A 1752 sketch by John Moale (1731-1798)—a prominent landowner and amateur artist—shows a two-story building. A later sketch shows a third story added, according to records at that time, to adjust to alterations in the street level. The Inn was constructed

“of wood, two stories and an attic, with dormer windows. The first story was plastered outside and the upper part weather-boarded. A lone flight of stairs from the outside led up to the second story. The building presented the appearance of an old-fashioned German hostelry. It was the grand hotel of the city. Washington, Lafayette and other revolutionary heroes stopped there.”(3)

In 1775, Acadians, descendants of French colonists who had settled in Canada’s East Coast Maritime Provinces, were being forced out by the British after the French and Indian War (1754-1763). Several boatloads were sent to Maryland in 1775 and many came to Baltimore, settling in “French Town” on South Charles Street. Many lodged at Kaminsky’s Inn, before continuing on to Louisiana, their initial destination, where the term “Acadian” eventually morphed into “Cajun.”

Kaminsky’s Inn “met its demise in the early 1870s when it was razed to make way for three iron-front buildings at 101-105 East Redwood Street. These buildings were in turn destroyed some 30 years later when the Great Fire of 1904 swept through downtown Baltimore. A dozen years passed before another edifice, the Sun Life Insurance Company Building, was erected.”(4)

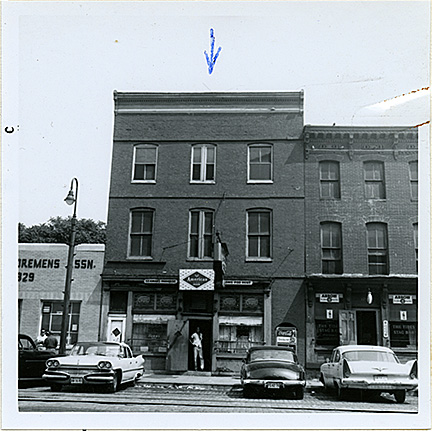

Bull’s Head Tavern, N. Front Street.

E. Sachse & Co.’s Bird’s Eye View of Baltimore(Detail), 1869, Baltimore City Life Museum Collection, CB 5457, MdHS (reference photo)

A tract of property located on North Front Street in “Old Town” Baltimore in 1732 was owned by Captain John Boring in an area known, at that time, as Jones Town. It was a bustling neighborhood of residences, industry and commerce. In 1812, Elizabeth Edwards inherited this parcel of land and building from the Boring family and, with improvements, opened the Tavern House in 1836. By 1880, it became known as the Bull’s Head Tavern and operated under that name until the building was purchased in 1900 by a Russian tailor named Simon Friedman. No records remain to indicate it remained a tavern—the building was later converted to an auto repair shop and by the 1950s replaced by a parking garage.

In 1998, sixteen youth, many from the Juvenile Justice System, helped archaeologists uncover relics from Baltimore’s past during excavation for the future Juvenile Justice Center on Gay Street. Among the curiosities unearthed were spittoons, utensils, food bones, hundreds of sugar molds from an early 19th century sugar refinery, and the foundation of the Bull’s Head Tavern.(5)

Fountain Inn, Light Street and German Street, 1871?, Baltimore City Life Museum Collection, MC5915, MdHS.

The Fountain Inn opened in 1773 at the southwest corner of what is now Baltimore and Hanover Street. It was built in what was then termed the Old London Style with balconies around a tree shaded courtyard. In 1775 the Inn played host to General George Washington on his way to the Continental Congress and again in 1781 when we was en route to Yorktown. Washington stayed at the Inn again in 1783 when he traveled to Annapolis to resign his commission as Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army. His wife Martha also lodged at the Inn on her frequent trips to visit her husband at his various encampments. The Fountain Inn became the headquarters for the Patriots of the Whig Society—American Whigs were those colonists of the Thirteen Colonies who rebelled against British authority during the Revolution. The Inn weathered the storm of the War of 1812 and the Marquis de Lafayette, during this visit to the United States in 1824-1825, had a suite reserved for him there.

The Fountain Inn was razed in 1871 to make room for the Carrolton Hotel, which occupied the site until it was destroyed by the 1904 fire. Lavish for its time, the Southern Hotel opened its doors on this site in 1918 and remained there until 1964. Today the site is a parking lot.

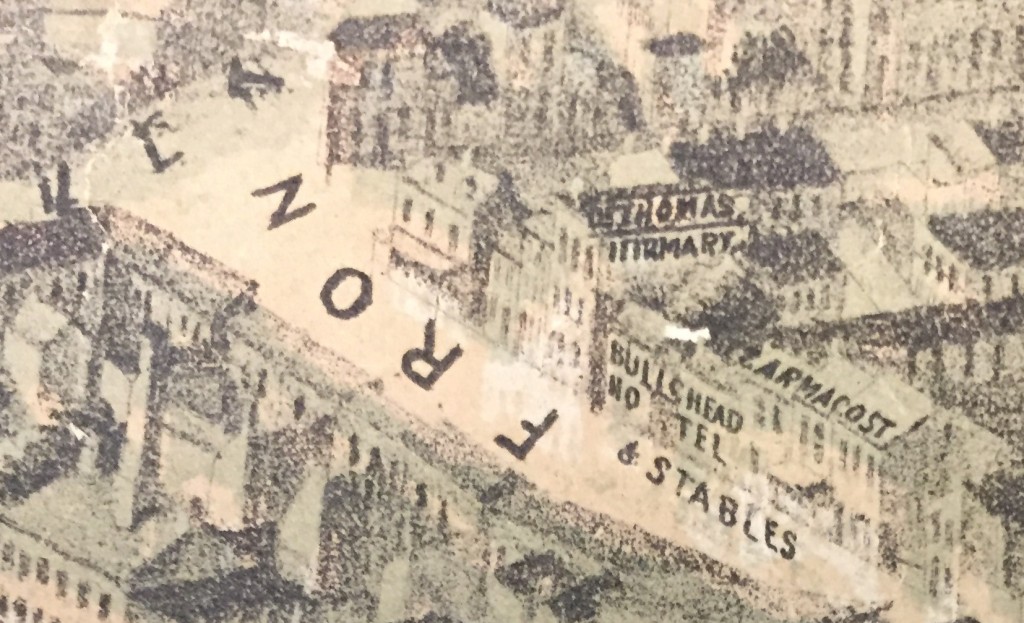

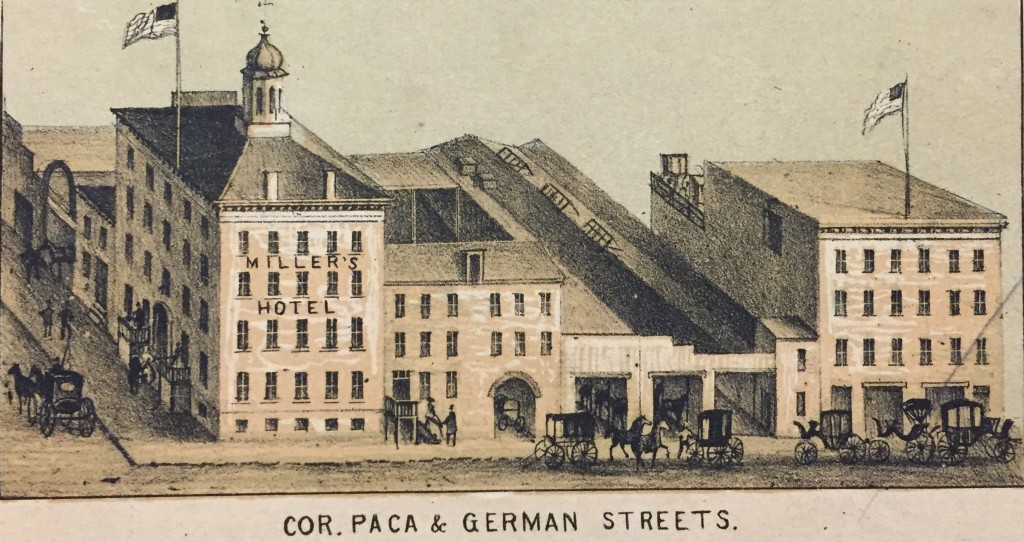

Miller’s Hotel, formerly the Maypole Tavern, 16-18 S. Paca Street (note the livery stables)

E. Sachse & Co.’s Bird’s Eye View of Baltimore(Detail), 1869, Baltimore City Life Museum Collection, CB 5457, MdHS (reference photo)

The Maypole Tavern, in existence at least as early as 1824, was located at 16-18 S. Paca Street at the corner of German (now Redwood) Street. The Maypole was a favorite stopping point for waggoners passing through Baltimore. The first known owner was Henry Clark who operated it until his death in 1836. James Adams took over from Clark—his successor was Isaac Wilson who had been an agent for the B&O Railroad. The National Road, the first major highway in the United States was signed into law by Thomas Jefferson in 1806. Also known as the Cumberland Road, its’ purpose was to open up the West when construction started in 1811. The National Road connected Baltimore with the “Old National Pike” in 1824 and it brought business to the May Pole Tavern, along with others. According to the B&O Employees Magazine, some emigrants staying at the Maypole Hotel started their journey west ward from that point.

In 1849, brothers Horatio and William Miller purchased the Maypole and renamed it “Miller’s Hotel.” They may have been more interested in the livery stables that were attached, which could accommodate up to 250 horses. The site, with a number of subsequent owners, remained a tavern until 1897, when it was converted into a warehouse. The livery stables continued to operate until around 1920. In the 1940s the building was torn down. Today the University of Maryland’s School of Social Work occupies the site.(6)

General Wayne Inn, northwest corner Paca Street and Baltimore Street, not dated, Baltimore City Life Museum Collection, CC84, MdHS.

The Complete View of Baltimore published by Samuel Young in 1883 listed many of the taverns that were in business at the time, but have since gone by the wayside:

Three Tuns Tavern (aka Three Tons Tavern) – Pratt & Paca Street

General Wayne Inn – Baltimore and Paca Streets

Hand Tavern – Paca Street near John Street

Indian Queen – Baltimore and Hanover Streets

Franklin Inn – Franklin and Paca Streets

Golden Horse Tavern – Howard and Franklin Streets

Cross Keys Tavern & Philadelphia Stage Office – 116 High Street

Rising Sun Tavern – High Street

Old Hays Scales Tavern– Forrest and Hillen Streets

Hand in Hand Tavern – Paca Street between Lexington and Saratoga Streets

Lost Breweries

There were well over 100 breweries in Baltimore’s history. The four most Baltimoreans remember are: the National Brewing Company, home of Natty Boh; the Globe Brewing Company with their Arrow Beer Hits the Spot commercials; the George Gunther Brewing Company and its “Dry-Beery Beer”; and the American Brewery whose iconic building at 1701 North Gay Street was recently restored.

National Brewing Company, Conkling at O’Donnell Street, June 1949, BGE-20897, Baltimore Museum of Industry.

The National Brewing Company, founded in 1872 at the corner of Conkling and O’Donnell Streets was a small brewery producing a high quality beer, National Premium. The brewery expanded its product line in 1885 when they began brewing barrels of National Bohemian beer. They delivered the barrels with horse drawn wagons and maintained stables on the brewery’s premises. The company shut down at the onset of Prohibition because, unlike their two local competitors, Gunther and Globe, they decide not to produce “near beer”—beer with less than half of 1 percent alcohol content by volume.

When the 18th Amendment was repealed on April 7, 1933, local businessman Samuel Hoffberger bought the company, modernized it, and began producing beer. When his son Jerold was discharged from the armed services in 1945, he joined the company and the following year became president. For the next 28 years, under his guidance, the company thrived producing up to 230,000 barrels of beer a year.

Jerold also ushered in the era of “Mr.Boh,” a character with slicked down hair, with a curl on each side, one eye and a handle bar mustache. Advertised as the brew “From the Land of Pleasant Living,” it continued to grow and innovate—on the way introducing the six-pack. In 1953, the Colts joined the National Football League and Hoffberger produced a malt liquor called Colt 45. The can showed a kicking horse and horseshoe.

Natty Boh became the company’s symbol in 1954 after Jerold bought the Oriole baseball team and the beer was sold at Baltimore’s Memorial Stadium. In 1975 National Brewery merged with Canada’s Carling Brewery and together they had a brewing capacity of 1.9 million 31 gallon barrels of beer a year. But the merger proved unsuccessful and Carling-National was sold to the G. Heileman Company shortly thereafter.(7)

In 1748 brothers John and Daniel Barnitz established the Globe Brewery at 327 S. Hanover Street. It later achieved notoriety for its’ Arrow Beer, a mainstay in 20th Century Baltimore. Like so many of the early breweries, this one changed hands several times over its 200 year life span. The brewery started making ale, but when Peter Gloninger, of German descent, took over the company in 1820, lager beer was added to the product line.

Samuel Lucas bought the firm after it had passed through several hands and under his direction it became the second largest brewery in Baltimore, producing about 7,000 barrels per year of porter and ale. Lucas died in 1856 and ownership passed to a Frenchman, Francis Dandelet and then on to John Butterfield in 1876, although Dandelet remained with the company until his death in 1878.

Butterfield’s addition of Frederick H. Gottlieb, his son-in-law, set the company on a new course and in 1888 the Globe Brewing Company was formed. Gottlieb joined a company that became Wehr-Hobelam-Gottlieb & Company which made barley and rye malt. The old brewery was torn down and a new seven story malt plant built, which produced malt from 1881-1888, when the company returned to making beer. In 1889 Globe joined with 16 other breweries to form the Maryland Brewing Group with Globe as the central office, but this conglomerate broke apart as with Prohibition on the horizon.

Boston Iron and Metal Company was in the scrap metal business and bought the brewery for scrap in November 1919 but the new owners decided to try their luck producing beer instead. A contest to name their beer ran which produced the well known “Arrow Special-It Hits the Spot.” Producing “near beer” got them through prohibition. John Fitzgerald, brewmaster at the time, became the first brewer to produce legal beer when Prohibition ended. The Globe Brewing Company went on to become one of Baltimore’s best known brands, making Arrow Beer as well as Shamrock Ale, Arrow Ale and Arrow Bock, until it ceased operations in 1963.(8)

J.F. Wiessner and Sons Brewery Company building, 1700 N. Gay Street, ca. 1915, Baltimore City Life Museum Collection, MC7104, MdHS.

The American Brewery located at 1701 North Gay Street was first established as the John F. Weissner & Sons Brewing Company. Built in 1877, it was a complex of five buildings. The brewery occupied 1700-1702 North Gay and the Bottling Plant was located at 1704-1710 North Gay. Just down the street was another brewery owned by George Bauernschmidt. Both of these breweries had the first ice making machinery in Baltimore. Wiessner plant production reached 110,000 barrels per year by 1919. The Wiessner family lived across the street and their residence was large enough to house some of the workers coming from Germany.

Prohibition took its toll and the Weissner Brewery shut its doors in 1920. The property was sold to the American Malt Company who started making American Beer in 1950. The plant shut down in 1973, but their magnificent building remains today, restored and occupied by the Baltimore Headquarters for Humanities, non-profit providing mental health and vocational services for the disabled and the disadvantaged.

One of the brewery’s most famous symbols, the statue of King Gambrinus , the patron saint of beer was restored and now resides at the Maryland Historical Society.(9)

Established in 1900, Gunther Brewery, located at Conkling and Toone Streets, was officially named the George Guenther Jr. Brewing Company (note the dropped “e”). Twenty years earlier George Guenther Sr. took over the Gehl Brewery and after a fire damaged the building he built a new one in 1887. He operated the brewery until 1899 when he sold the business to the Maryland Brewery, and as part of their agreement he could not open another brewery in his name—so he started a new concern in 1900 using his son’s name, George Guenther Jr. Brewing Company. They had the foresight to anticipate Prohibition and began brewing “near beer” in 1919. After Prohibition ended Gunther proceeded to expand its business and was so successful, Hamm’s Brewing Company bought them out in 1960. As consolidation in the industry continued, the F&M Shaefer Company bought out Hamm’s three years later. The Shaefer Company continued to produce both Hamm’s and Gunther until 1978.(10) Today the Gunther Apartments, at 1211 South Conkling Street, keep the name of that old brewery alive. (Sidney Levy)

Sidney Levy is a volunteer in the Special Collections Department at the Maryland Historical Society.

King Gambrinus, 1879.

This statue of the icon of the brewing industry, the earliest surviving zinc sculpture of its kind, originally stood in a niche above a door at the J.F. Wiessner & Sons Brewery at 1701 N. Gay Street.

King Gambrinus, 1879, Museum Collection, 2000.23, MdHS.

Some Lesser Known Baltimore Breweries That Have Vanished:

George Bauernschmidt Brewery, established 1900 – Gay and Oliver Streets

Darley Park Brewery, established 1900, Harford Road

Bayview Brewery – O’Donnell Street at Conkling Street

Eigenbrot Brewery – Wilkens Avenue

Eurich’s Beer – Mt.Vernon Brewery Company, foot of Ridgely Street

Brehm’s Brewery – N.E. corner of Belair Road and Erdman Avenue

Bernhard Berger’s Lager Beer Brewery –Belvidere Street near Greenmount Avenue

Chesapeake Beer Bottling Company – 424 West Baltimore Street

J.H.Von ded Horst & Sons–Eagle Brewery – Belair Road Extended

Jackson & Tucker “Iron Beer” – 6 South Howard Street

Thos. B. Cooke – 1426-28 Eastern Avenue

Oriental Brewery – Third and Lancaster Streets in Canton

In the 1940 Baltimore City Directory the following breweries were listed but no longer exist:

American Brewing Company Inc. – 1700 N. Gay Street

Bismarck Brewing Company – 1808 N. Patterson Park Avenue

Bruton Brewing Company – 3501 Brehms Lane

Free State Brewing Company – 1108 Hillen Road

Globe Brewing Company (Arrow beer) – 327 S.Hanover Street

Gunther Brewing Company – 1211 S. Conkling Street

Imperial Brewing Company – 1838 N. Patterson Park Avenue

National Brewing Company – Conkling & O’Donnell Streets

Sources and Further Reading:

(1) Prohibition in the United States, Wikipedia

(2) Ibid.

(3) “A Leaf from the Past,” The Baltimore Sun, December 5, 1885.

(6) Paca Street (16-18 South), Passano-O’Neill File, MdHS.

(7) National Brewing Company, Wikipedia; Kilduff’s Old Baltimore Breweries

(8) Globe Brewing Company, RustyCans.com; Kilduff’s Old Baltimore Breweries

(9) The History of Breweries in Baltimore; Baltimore Brew, Kilduffs Old Baltimore Breweries

(10) Gunther Brewery-George Gunther Brewing Co., of Baltimore-Peared Creation