Lost No More: Recovering Frances Ellen Watkins Harper’s “Forest Leaves”

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper’s first book of poems had been considered lost to history for well over one hundred years. U-Mass graduate student Johanna Ortner shares the tale of recovering this incredibly valuable text–reblogged from Common-Place.org

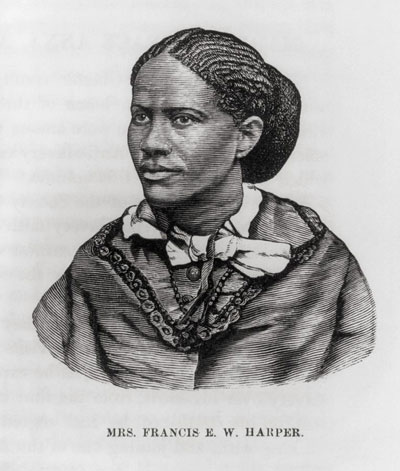

Portrait, “Mrs. Frances E.W. Harper,” engraving taken from The Underground Railroad…, by William Still. (Philadelphia: Porter & Coates, 1872). [Photo taken from the web.]

My home is where eternal snow

Round threat’ning craters sleep,

Where streamlets murmur soft and low

And playful cascades leap.

Tis where glad scenes shall meet

My weary, longing eye;

Where rocks and Alpine forests greet

The bright cerulean sky.

(While Forest Leaves was published under Harper’s maiden name, Watkins, I refer to her throughout the article as Frances Harper, because she is more commonly known by her married name; further, it will avoid any confusion with her uncle William Watkins.)

In her poem titled “Yearnings for Home,” Frances Ellen Watkins Harper describes how she longs to be back home in her mother’s cot in order to pass away peacefully in the familiar surroundings of home. Harper beautifully depicts the rural landscape that surrounds her mother’s little house as a heavenly, blissful place. Those who know Frances Harper and her literary works might feel taken aback by the above-mentioned poem, because it was not printed in any of her known literary publications before or after the Civil War. Indeed, “Yearnings for Home” is only included in Harper’s first pamphlet, titled Forest Leaves, which was deemed lost to history for more than 150 years. This article introduces that long-lost publication to readers, scholars, and archivists.

A Lost Text Found

As I began to research my dissertation, “’Whatever concerns them, as a race, concerns me:’ The Life and Activism of Frances Ellen Watkins Harper,” which chronicles Harper as a seminal figure in black women’s protest tradition and aims to highlight her political activism, I started in Maryland, the state of her birth. To be honest, I had no clear concept of how to go about conducting archival research on a figure like Harper, who did not leave behind, as far as we know, any personal papers, other than letters and speeches, some of which were published in newspapers, such as The Christian Recorder andThe National Anti-Slavery Standard.

I decided to begin with the H. Furlong Baldwin Library at the Maryland Historical Society, which is located in Harper’s hometown of Baltimore. Having done my secondary source reading on her, I knew that Forest Leaves was deemed lost. Call it my naiveté as a young graduate student, but I figured I might as well type in the title in the society’s catalog. Voilà, it came up, together with a collection number. Even as I stared at the number on my screen, I thought that it could not be the “real deal,” but instead was maybe a copy of the cover, or a newspaper clipping discussing the pamphlet (my naiveté knew no bounds). Fast forward to when the MdHS special collections archivist placed an envelope with the call number in front of me. I opened it up, peeked inside and wanted to let out a high-pitched squeal that I had enough sense to repress at the last second. The pamphlet slid right out of the envelope into my hands and there it was, staring me in the face. The term surreal is appropriate for how I felt when I first perused the pages of Forest Leaves. As I am writing this essay, I still catch myself looking at my copy, double-checking the cover of the pamphlet, making sure that I am not imagining the title. I have to reassure myself that I am not hallucinating: finally, scholars and students will be able to read Harper’s first published work and include it in their teachings and studies alike. Forest Leaves does not include a publication year, but the found copy of the pamphlet is likely not from the year 1845, which initially was proposed as the publishing date by other scholars, since James Young’s shop was located on Gay Street during that year, and not at Baltimore and Holliday as stated in the pamphlet. This could either mean that Forest Leaves was not originally published in 1845, or that a different printer printed it that year and no record survived. In the following year, 1846, Young printed an almanac, published by J. Moore, still citing his Gay Street address. In 1853, he printed a lecture by Harry Young on the rise in crime, and the printing location is the same as in Forest Leaves. This indicates that James Young moved his business from No. 3 Gay Street to the corner of Baltimore and Holliday Streets sometime between 1846 and 1853, and that he printed this copy of Forest Leaves during that time period. Keeping in mind that Harper moved to Ohio to teach at Union Seminary in 1851, it is safe to state that her first pamphlet was published sometime in the latter half of the 1840s, when she was in her early twenties.

A Key to Harper’s Early Life

The retrieval of Forest Leaves not only gives us an earlier starting point for Harper’s writings, but it is also the only primary source we have from her young life in Baltimore, before she joined the abolition movement in 1854 and began her decades-long career as a committed writer and activist for major social reform movements during the nineteenth century. Harper was raised by her uncle William Watkins, who took her in after she became an orphan at the age of three in 1828. Watkins was a renowned minister, educator, and avid abolitionist in Baltimore. He taught in his own school, the Watkins Academy for Negro Youth, which, according to Frances Smith Foster “was well known for its emphasis upon biblical studies, the classics, and elocution.” Harper was one of his students until she was about thirteen years old and began to work as a domestic servant for a couple who owned a bookstore in the city.

Very little is known about Harper’s childhood and young adulthood in antebellum Baltimore, where she lived with her uncle William Watkins’ family in the city’s eleventh ward. Being born in a city with the largest free black population in the nation in the decades leading up to the Civil War, Harper grew up in an environment that displayed an intimate geographic proximity to slavery, since Maryland was a slave state. While we do not have autobiographic sources by Harper describing the first—roughly—twenty-five years of her life in Maryland, it is safe to state that her uncle had a great influence in shaping the young Harper’s mind and writing development. Due to Watkins’ position as the founder of his own academy, Harper had the advantage of receiving a formal education at a time when access to schools was either greatly restricted or impossible to obtain for African American children. Leroy Graham lists the subjects taught at Watkins’ academy as “History, Geography, Mathematics, English, Natural Philosophy, Greek, Latin, Music, and Rhetoric” and describes Watkins as “a grammarian of such precision in the way of etymology, syntax, prosody, and so on, that one of his former pupils wrote humorously of the old leather strap Watkins used to correct grammar misuses.” This account of the teacher’s strict expectations allows us to safely assume that Harper not only learned basic literacy in her uncle’s school, but was also taught the composition and style that is needed to write well-developed poems. The rediscovered pamphlet testifies to Harper’s access to a strong formal education, which made her stand out from the majority of the nation’s black population, who were denied such access.

She was not the first one in her family to use the medium of print in order to have her voice heard. Her uncle William Watkins had his letters published in newspapers like Freedom’s Journal and The Liberator, discussing the need for abolition and expressing his strong dislike for colonization—the plan to repatriate all free black people to Africa. One could argue that Harper must have been familiar with Watkins’ activism and publications and perhaps this was the inspiration for her to seek to have her own work read outside of her family’s household. While the pamphlet was written by Harper herself, one has to acknowledge how her familial surroundings helped her develop and nurture her growing desire to write for public consumption.

Forest Leaves gives us insight into Harper’s desire to publish her works for a public readership while she was still living in Baltimore and had not, as yet, joined the abolition movement.

Insights into Nineteenth-century Black Print Culture and Harper’s Body of Work

The pamphlet functions as our “new” starting point for Harper’s introduction into African American literary history and allows us the opportunity to discuss how she was able to distribute her first poems within the nation’s burgeoning print culture. Forest Leaves was published by printer James Young, who founded and lead temperance organizations in Baltimore. As Patricia Dockman Anderson has shown, Young owned a printing business, but was also a leader in the Maryland temperance movement, helping to found Maryland’s branch of the Sons of Temperance organization in Harper’s hometown. According to the title page of Forest Leaves, Young’s printing business was at the corner of Baltimore and Holliday streets. An advertisement in the Baltimore Wholesale Business Directory for 1845 lists Young’s printing press at No. 3 South Gay Street and states that he would “execute every description of printing as cheap and well as any other establishment in the city.” It’s likely that the prospect of an affordable print run influenced Harper’s choice of Young’s business for her first collection of poems. Having books and pamphlet printed was not a low-cost venture for writers during that time, and Harper certainly could not have paid high prices on her domestic servant’s salary.

The publication of Forest Leaves provides a prehistory for the other literary works Harper wrote when she became one of the most well-known black women activists of the nineteenth century. After Harper left Baltimore to eventually work as a traveling lecturer for the Maine Anti-Slavery Society and later the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society during the mid to late 1850s, she published her second pamphlet, titled Poems on Miscellaneous Subjects, in 1854. After the Civil War ended and slavery was officially abolished, Harper became active in the women’s rights and temperance movements and continued to publish (serialized) novels, such as Minnie’s Sacrifice, Sowing and Reaping, Trial and Triumph, and Iola Leroy, as well as collections of poems. Harper died in Philadelphia in 1911. Frances Smith Foster points out that “Harper’s literary aesthetics were formed during the first half of the nineteenth century, and her commitment to a literature of purpose and of wide appeal remained constant.” This constancy is evidenced by a writing style, which, we can now see, did not change much after her first pamphlet. However, while her later publications, including her novels, were certainly more political and focused on black life, her first pamphlet centers heavily on Christianity. Importantly, Forest Leaves marked the first stepping-stone of a literary career that would earn her a spot as one of the most influential and celebrated African American women writers.

A Case Study in the Politics of Authentication

Forest Leaves provides a new site to discuss the practice of authenticating black writers’ literary productions during the antebellum period. Black writers like Phillis Wheatley, Ann Plato, and Harriet Jacobs, who published their works during the 1770s, the 1840s, and the 1860s respectively, relied on well-respected community leaders/activists to write prefaces that would vouch for their intellectual writing capabilities. Harper’s own 1854 pamphlet Poems on Miscellaneous Subjects includes such a preface by none other than abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, most likely because of her emerging public persona as an abolitionist lecturer and the use of the pamphlet as a piece of literature that spoke out against the enslavement of millions of African Americans in the South. Yet Forest Leaves has no such authenticating material. Does the lack of a preface in Forest Leaves suggest that Harper did not mean for it to be published for public consumption? Or, we might ask, did she actively opt not to have an authority like her well-known uncle vouch for her authenticity as an author?

In The Underground Railroad, William Still wrote that “the ability [Harper] exhibited in some of her productions was so remarkable that some doubted and others denied their originality.” With this in mind, Harper’s omission of a preface for Forest Leaves can be read as a conscious effort to distance herself, as a young black woman in her early twenties, from white America’s desire and need to have (predominately) white men function as creditors for black intellectual publications. She could very well have viewed her pamphlet as her first foray into the literary world and was content with publishing her creative expression without someone else’s written stamp of approval.

Portrait of Frances E.W. Harper by Leroy Forney commissioned by First Unitarian Church of Philadelphia.

New Poems, and New Origins for Known Work

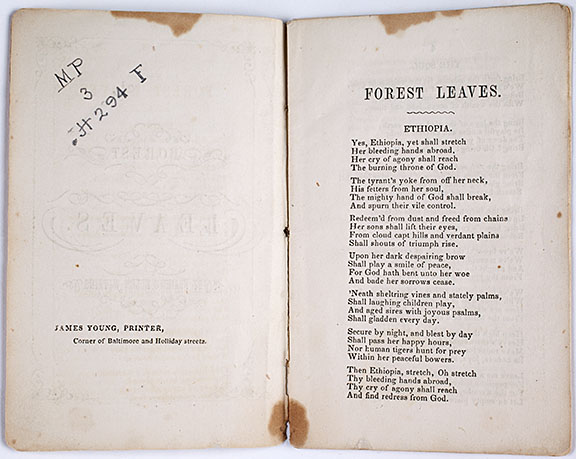

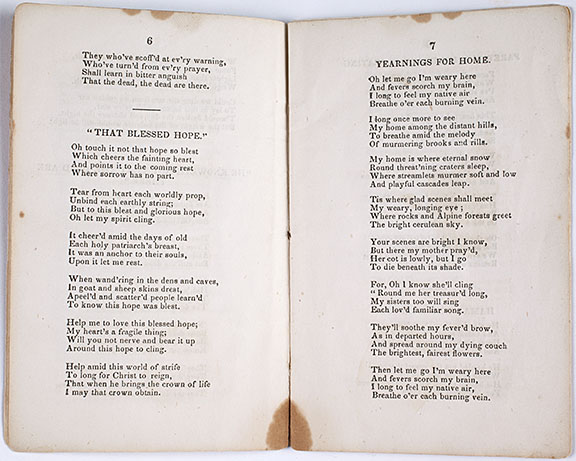

The content of Forest Leaves itself provides a rich new site of study for scholars of African American literature and history, and for researchers of book history and print culture. To begin with, we now have earlier versions of poems scholars are familiar with through her already known literary productions. Forest Leaves’ poem “The Soul” was republished in the Christian Recorder in 1853, according to Foster’s citation of Daniel Payne in A Brighter Coming Day. “Bible Defence of Slavery,” “Ethiopia,” “That Blessed Hope,” and “The Dying Christian” were republished in Harper’s 1854 pamphlet,Poems on Miscellaneous Subjects. Two poems from Forest Leaves, namely “He Knoweth Not That The Dead Are There” and “For She Said If I May But Touch Of His Clothes I Shall Be Whole,” were also included in her second pamphlet, but with different titles, “The Revel” and “Saved By Faith,” respectively.

Page 1 of Forest Leaves by Frances Ellen (Watkins) Harper, c. 1849. Rare Books Collection, MdHS. (MP3.H294F)

According to an advertisement in the newspaper the National Anti-Slavery Standard from June 6, 1857, Poems on Miscellaneous Subjects was for sale at the Philadelphia Anti-Slavery Office for 37 cents and could “be had at short notice and at the current price, by applying at this office.” Her poem “Ruth and Naomi” was included in the pamphlet’s 1866 edition. Also, “I Thirst” resurfaces, with minimal corrections from the original version in Forest Leaves, in the National Anti-Slavery Standard on October 9, 1858, and is reprinted in Harper’s 1873 edition of her publication Sketches of Southern Life. The poem “A Dialogue” was republished in the Christian Recorder on July 3, 1873, as stated in A Brighter Coming Day. While Harper republished “I Thirst” in an anti-slavery newspaper a few years after the publication of Forest Leaves, it is interesting to note that she held on to “A Dialogue” for more than twenty years before republishing it again in a newspaper. Further, the content of “A Dialogue” shares clear commonalities with her short story “Shalmanezer, Prince of Cosman,” which, according to Melba Boyd, “is concerned with the pitfalls of man’s materialism,” and is published in the 1887 edition of Sketches of Southern Life. Thus, one can see how her earliest work continued to influence and inspire her later literary productions.

Because of the pamphlet’s discovery, we know now that none of these already known poems were reproduced in their original form, but were revised in various ways for the 1854 publication. Further, most of these poems were at least one verse longer in Forest Leaves, and Harper altered punctuations as well as various words in her revisions. This discovery alters our understanding of these previously studied poems, as they now must be understood as revisions of earlier works. Harper’s choice to reprint these early works allows for the conclusion that she was, despite some alterations, satisfied with her literary productions before she formally joined the abolition movement and became one of the most well-known nineteenth-century black women writers. The fact that “Bible Defence of Slavery” was originally written for Forest Leaves testifies to the young writer’s growing activist mindset, exemplifying her critique of slavery while she was still living in Baltimore. Further, it shows her uncle’s influence on Harper’s evolving thoughts on slavery, as Watkins himself published various letters in Frederick Douglass’ Paper in which he voiced his contempt for Christians and ministers who used the Bible to justify the enslavement of millions of African Americans.

The ten new poems are, of course, exciting additions to Harper’s body of work. Half of the newly recovered poems in Forest Leaves focus on religion and Christianity, which function as dominant themes throughout her career as a writer. Harper’s focus on Christianity as a central topic in her first pamphlet emphasizes the fact that religion played—as it still does to this day—a key component in the lives of African Americans. According to Frances Smith Foster, biblical studies were part of the Watkins Academy’s school curriculum.

William Watkins was also a minister at Baltimore’s Sharp Street Methodist Episcopal Church and thus religion was probably a central part of his family’s life, which is reflected in the Christian themes of most of the poems in Forest Leaves. Further, Harper stays within the limits of female respectability by writing about religion, which is not surprising for a young, free black woman who was consciously defying societal norms by publishing her literary works for a potentially broad audience. This fact is further underlined by her use of romanticism and sentimentalism in the poems “Let Me Love Thee” and “Farewell, My Heart Is Beating.” These works could be expressions of a young Harper’s awakening sense of love and romance, something she did not address again in her subsequent poems; by exploring these topics in her writing, she again remains within the boundaries of proper femininity, while expressing herself through the public medium of print culture.

In sum, Forest Leaves represents a new vista for scholarship on Frances Ellen Watkins Harper by not only expanding the cannon of her literary work, but by also adding to a broader genealogy of antebellum black women’s literature. Writing in the decades leading up to the Civil War, African American men and women affirmed and fought for their right to be seen as full citizens in a country that continuously portrayed them as inferior and lacking in intellectual capabilities. Education became one of the crucial pillars of the black freedom struggle. Due to people like Harper’s Uncle Watkins, the succeeding generation of black activists, which included Harper, were able to put their demands, thoughts, and ideas into writing, defying stereotypes. Forest Leaves is illustrative of the success of the antebellum black fight for literacy and education, while adding to the field of early African American literature. (Johanna Ortner)

Pages 6 & 7 of Forest Leaves by Frances Ellen (Watkins) Harper, c. 1849. Rare Books Collection, MdHS. (MP3.H294F)

Johanna Ortner is a doctoral candidate in the W.E.B. Du Bois Department of Afro-American Studies at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Originally from Scheibbs, Austria, her dissertation project is titled “‘Whatever concerns them, as a race, concerns me:’ The Life and Activism of Frances Ellen Watkins Harper.”

Further Reading

Melba Boyd’s Discarded Legacy: Politics and Poetics in the Life of Frances E.W. Harper 1825-1911 (Detroit, 1994), Frances Smith Foster’s A Brighter Coming Day: A Frances Ellen Watkins Harper Reader (New York, 1990), and Maryemma Graham’s Complete Poems of Frances E.W. Harper (New York, 1988) are essential to learning more about Harper’s life and literary works. In regard to Harper’s recovered serialized novels Minnie’s Sacrifice, Sowing and Reaping, Trial and Triumph: Three Rediscovered Novels by Frances E.W. Harper (Boston, 1994), edited by Frances Smith Foster, as well as Eric Gardner’s article “Sowing and Reaping: A ‘New’ Chapter from Frances Ellen Watkins Harper’s Second Novel” (Common-place 13:1, October 2012) are crucial reads. Hilary J. Moss’s book Schooling Citizens: The Struggle for African American Education in Antebellum America (Chicago, 2009) includes a detailed section on black educational activism in Baltimore, focusing on Harper’s uncle, the minister and educator William Watkins. Also, in Baltimore: The Nineteenth Century Black Capital (Washington, 1982), Leroy Graham dedicates one chapter to a biographical study of William Watkins and his influence on Baltimore’s black community. Patricia Dockman Anderson’s dissertation and forthcoming book “By Legal or Moral Suasion Let Us Put it Away:” Temperance in Baltimore, 1829-1870 (University of Delaware, 2008) discusses the printer James Young’s leadership role in the movement. Barbara Jeanne Fields’ Slavery and Freedom on the Middle Ground: Maryland during the Nineteenth Century (New Haven, Conn., 1985) and Christopher Phillips’ Freedom’s Port: The African American Community of Baltimore, 1790-1860 (Chicago, 1997) analyze the complexities of the black community’s lived experiences in Harper’s city of birth.

Acknowledgments:

Ms. Ortner would like to thank Dr. Manisha Sinha, Dr. Britt Rusert, Dr. Anna Mae Duane, and Dr. Paul Erickson for their invaluable expertise and for their help with the digitization process of the pamphlet. I am also grateful to the Maryland Historical Society—especially Mark Letzer, Joe Tropea, Damon Talbot and James Singewald—for their assistance in retrieving and processing Forest Leaves for this publication. Lastly, I would like to thank the University of Connecticut, and in particular, the Department of English, the Department of History, and the University of Connecticut Hartford campus, for providing the necessary funds to present Forest Leaves online to the public.