Scenes from the ’70s: The East Baltimore Documentary Photography Project

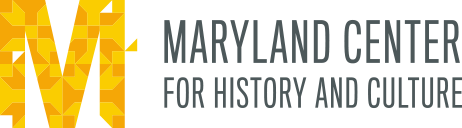

Sideshow performer, painted screen artist, photographer, and lifelong East Baltimore resident Johnny Eck (1911-1991) with his dog, Reds, on the stoop of his home at 622 N. Milton Avenue in McElderry Park. Eck (nee John Eckhardt Jr.), born without the lower half of his body, was born, lived and died in the Eckhardt family residence on Milton Avenue. Eck is only one of the more famous residents of East Baltimore photographed for the East Baltimore Documentary Photography Project between 1976 and 1980. “The Amazing Johnny Eck,” an exhibition featuring Eck’s memorabilia and works, is currently on display at MICA until March 16, 2014.

Johnny Eck, ca. 1977, Linda G. Rich, The East Baltimore Documentary Photography Project, Baltimore City Life Museum Collection, 1982.19.1.178, MdHS.

In 1976, Maryland Institute College of Art photography professor Linda G. Rich, and two of her students, Joan Clark Netherwood and Elinor B. Cahn, began work on a project documenting the large swath of neighborhoods collectively known as East Baltimore. What was intended to be merely a project for Rich’s class on social documentary photography, instead evolved into a four-year undertaking, resulting in over 10,000 photographs, and a unique portrait of a neighborhood in transition.

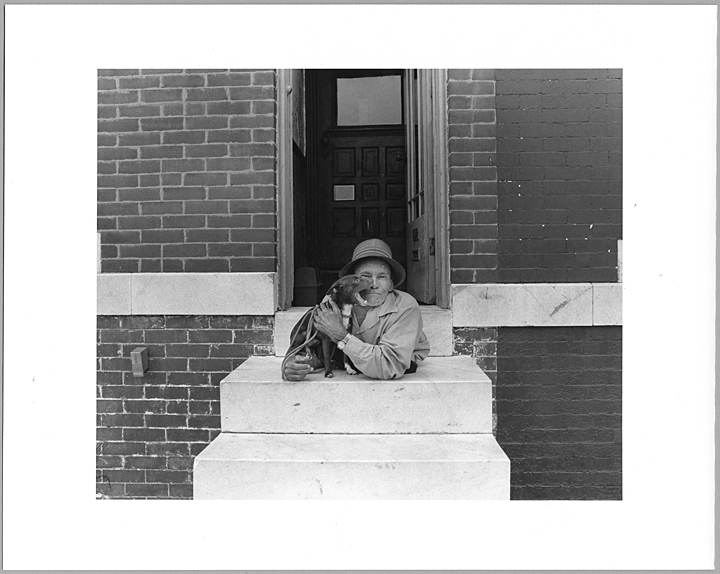

Nan Cotrella Coiffeurs in Canton a few days before Easter, April 1977, Jean C. Netherwood, The East Baltimore Documentary Photograph Project, Baltimore City Life Museum Collection, 1982.19.1.92, MdHS. (click to enlarge)

The inspiration for the project came about when Rich—a recent transplant to Maryland—attended the annual “I Am an American Day” parade in 1975. The event, held since 1938 in the Highlandtown-Patterson Park area, was first inaugurated to honor the U.S. Constitution, but over the years had evolved into “an opportunity for Baltimoreans to show their pride in being Americans.”(1) The parade was hugely popular, lasting for four hours or more and often attracting upwards of 300,000 onlookers, politicians, and celebrities, waving flags, singing, and marching. Rich was struck not only by the patriotic display of the celebration but by the unique characteristics of the surrounding neighborhood: the rows of clean, white marble steps, the vibrant painted screens, the window displays full of religious and patriotic iconography. She was particularly impressed by the strong sense of community she saw among the residents of the historically diverse section of the city.

East Baltimore, which consists of over 15 neighborhoods including Highlandtown, Middle East, Fell’s Point, Canton and Butcher’s Hill, saw its beginnings as a distinct area of Baltimore in the first half of the nineteenth century. Early inhabitants were mostly German immigrants, joined by a large number of Irish, and a sprinkling of other groups. An influx of Polish, Greek, Ukranian, Russian, Italian and other ethnic populations in the decades of the late nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries created a culturally diverse neighborhood, unified by Catholicism, patriotism, and tight-knit family and community ties. After World War II, these groups were joined by a growing African-American population, and a number of other arrivals including some Lumbee Indians and Applachian whites. One of the defining traits of the community was its rootedness—generations of families often lived in the same house or remained in the neighborhood their entire lives.

By the early 1970s theses traditions were in flux. A gradual deterioration had been taking place in the decades since World War II. A decline in industrial employment opportunities, an increase in crime, and the rise of suburban developments led to more and more of the younger offspring of the Eastern European community, in particular, abandoning the neighborhood and heading for the suburbs.

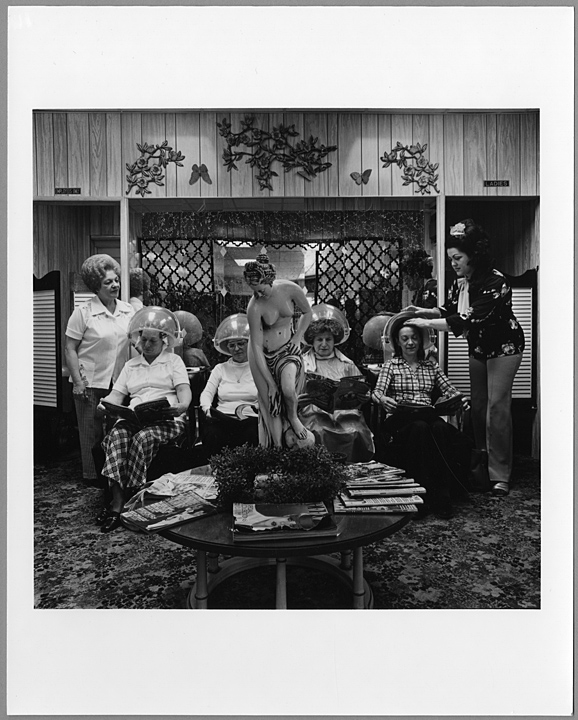

The Chicken Man David Yankelov, Lombard Street, 1979, Elinor B. Cahn, The East Baltimore Documentart Film Project, Baltimore City Life Museum Collection, 1982.19.1.133, MdHS. (click to enlarge)

In 1976, when Rich, Netherwood, and Cahn began their project, East Baltimore was entering a new period of revitalization. Residents, both the older and younger generations, were beginning to stay in the neighborhoods again. They were also taking more proactive measures to reshape the community. Residents banded together to put pressure on the city to improve basic services—trash pickup, street cleaning. On one occasion, a number of people formed a human chain across their street to prevent unwanted truck traffic. On a larger scale, community organizers formed the Southeast Community Organization (SECO) whose most notable success was halting the proposed highway system that would have run through Fell’s Point and Canton and displaced thousands of people from their homes.

The trio of MICA photographers set out to capture on film the community defined at that moment by what they saw as a sense of both “tradition and transition.” The photographs were staged to capture the sense of pride and identity they saw in the residents of the neighborhood—to allow the viewer to “see them as they see themselves.”(2) Although the women shot images of the well kept, narrow rowhouses, the marble steps, painted screens, and window displays that were a hallmark of East Baltimore, their focus was on the mostly working class residents themselves: the housewives, grocers, small business owners, industrial workers, priests, and families that formed the community. Most of the images are posed portraits with the subjects looking directly into the camera. They are in their homes, on their stoops, at work in factories, or behind the counters in family run delicatessens and grocery stores.

Since 1980, when the project was completed, East Baltimore has gone through further changes. In the 1990s many of the older residents began to leave once again. Most of the industries—the canneries, breweries, and packing warehouses—have been replaced by highrises, restaurants, and office buildings. Canton is now an upscale waterfront community; a small pocket of Highlandtown is an arts center. Many of the cultural artifacts have largely disappeared—the ubiquitous painted screens that could be found on rowhouses throughout the area are few and far between. The “I am an American Day Parade,” which had been held in Highlandtown for 56 years, moved to Dundalk due to funding issues in 1994. Fortunately, three MICA photographers have left us with a permanent document of a time and place that is largely part of history. (Damon Talbot)

(The Baltimore City Life Collection contains over 200 prints from the East Baltimore Documentary Photography Project; Copyright for the photographs are retained by the photographers, Linda G. Rich, Elinor B. Cahn, and Joan Clark Netherwood)

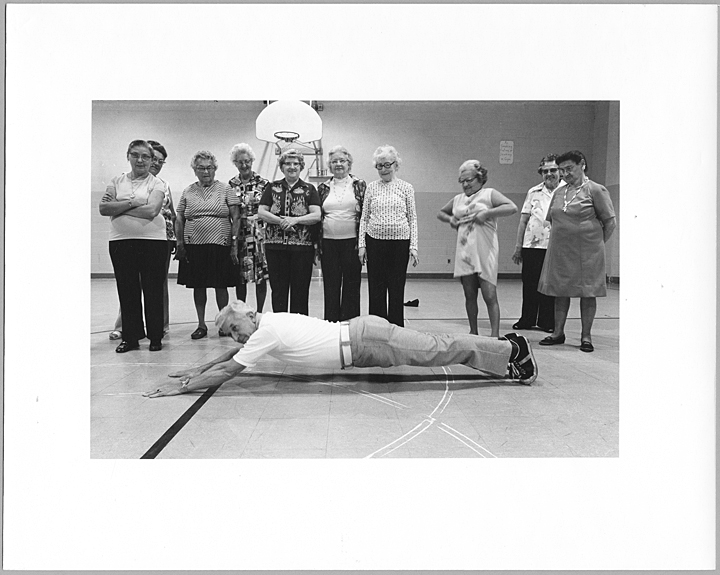

Senior Citizens Exercise Group, Patterson Park Recreation Center, Spring 1977, Joan Clark Netherwood, The East Baltimore Documentary Photography Project, Baltimore City Life Museum Collection, 1982.19.1.212, MdHS.

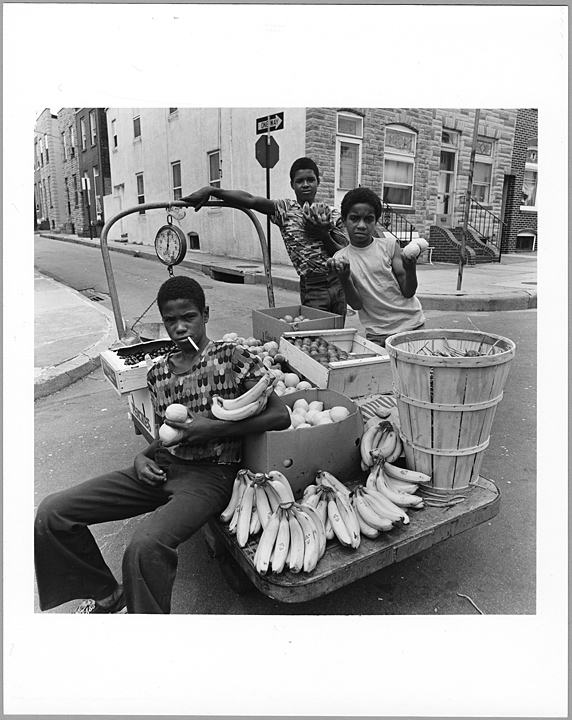

Young Hucksters, 1977, Elinor B. Cahn, The East Baltimore Documentary Photography Project, Baltimore City Life Museum Collection, 1982.19.1.136, MdHS.

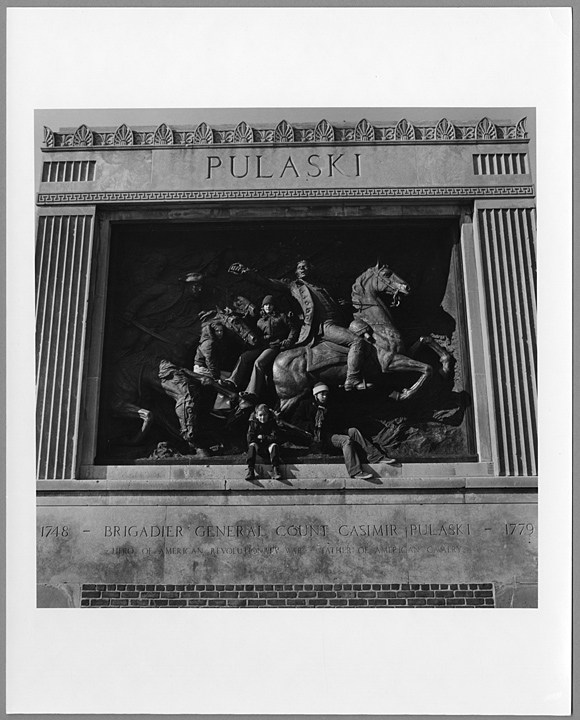

Brigadier General Count Casimir Pulaski monument, Patterson Park, Baltimore, January 1978, Jean C. Netherwood, The East Baltimore Documentary Photography Project, Baltimore City Life Museum Collection, 1982.19.1.57, MdHS.

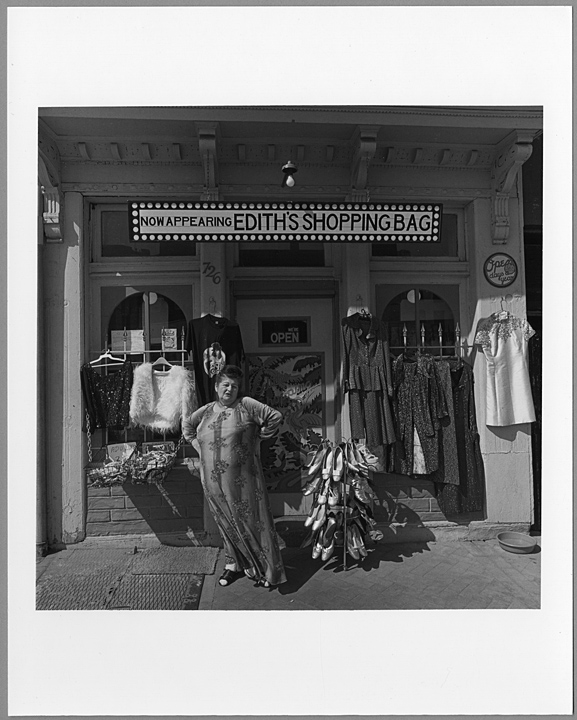

Actress and singer Edith Massey (1918-1984) in front of her thrift store at 726 S. Broadway. Massey was a regular in John Water’s films, appearing in five, including Female Trouble and Pink Flamingos. She also fronted the short lived punk band, Edie and the Eggs.

Edith Massey, South Broadway, Baltimore, 1980, Elinor B. Cahn, The East Baltimore Documentary Photography Project, Baltimore City Life Museum Collection, 1982.19.1.132, MdHS.

Chris Martin, Atlantic South Western Broom Company, Baltimore, 1977, Elinor B. Cahn, The East Baltimore Documentary Photography Project, Baltimore City Life Museum Collection, 1982.19.1.105, MdHS.

“Neighbors often visit on their front steps.”, East Baltimore Street, Butcher’s Hill, Baltimore, September 1978, Jean C. Netherwood, The East Baltimore Dcoumentary Photography Project, Baltimore City Life Museum Collection, 1982.19.1.192, MdHS.

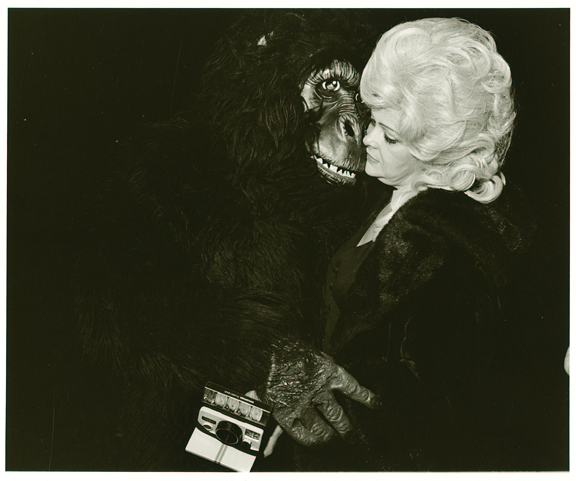

Highlandtown Halloween Parade, circa 1979, Linda G. Rich, The East Baltimore Documentary Photography Project, Baltimore City Life Museum Collection, 1982.19.1.190, MdHS.

“I am an American Day Parade,” East Baltimore Street, Baltimore, September 1978, Jean C. Netherwood, The East Baltimore Documentary Photography Project, Baltimore City Life Museum Collection, 1982.19.1.217, MdHS.

Sources and further reading:

(1) Atwood, Liz, “Lack of funds cancels ‘I am an American Day Parade’ for ’95,” The Baltimore Sun, September 12, 1995.

(2) Rich, Linda G., Joan Clark Netherwood, Elinor B. Cahn, Neighborhood: A State of Mind (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1981). p. 9.

Arnett, Earl, “East Baltimore photo project worth 1,000 words,” The Baltimore Sun, April 5, 1978.Eff, Elaine, The Painted Screens of Baltimore: an urban folk art revealed, (University Press of Mississippi, 2013).

Gold, Barbara, “Art Notes: Photos show what’s ‘special’ about East Baltimore,” The Baltimore Sun, April 23, 1978.

Olesker, Michael “’Neighborhood’ – a portrait of East Baltimore’s warm, extended family,” The Baltimore Sun, November 3, 1981.

MICA presents largest exhibition featuring slideshow performer Johnny Eck, Dec. 13-March 16.

Wise, Gabrielle, “3 Women photographers snap East Baltimore ‘social realism’,” The Baltimore Sun, May 18, 1977.