Thomas Poppleton’s Surveyor’s Map that Made Baltimore, 1822

This Plan of the City of Baltimore as enlarged and laid out under the direction of the Commissioners appointed by the General Assembly of Maryland in February 1818, Thomas Poppleton, 1823 (1852), Large Map Collection, MdHS.

Between 1776 and 1820 Baltimore grew like kudzu on a riverbank. Geographically three settlements, the original town, Old town and Fell’s Point were legally merged into one and the official boundaries of the resulting BaltimoreCity (incorporated in 1797) were expanded to encompass 14.71 square miles by legislative fiat in 1817. In that period the resident population grew from about 6,000 to 63,000, of whom over 14,000 were slave and free blacks. In that period, as historian Sherry Olson points out, commerce was the mainspring of the city’s economy, fed by the constant stream of shipping in and out of the port, most of it legal, but some of it the product of piracy and, as the last decade ended, in its most adventuresome, dependent upon illegally feeding the revolutions in central and south America. Baltimore was a haven for risk taking merchants and sea captains, who with other townsfolk, also speculated in bank stock, precipitating a deep depression that lasted from 1817 to about 1820 ruining many of the commercial high rollers in Baltimore and elsewhere.

To land surveyors the decades between the American Revolution and the end of the War of 1812 were a profitable nightmare of sorting out who actually owned what property in town, including where the wharves, streets and alleys should run amidst the building boom prior to the financial collapse. In 1784 the legislature tried to impose some order on the chaos by requiring that a correct survey of the city be made. As an 1812 city ordinance pointed out, it was never carried into execution. A fragment of surveyors notes has survived, indicating that a valiant attempt was undertaken to conduct an accurate survey, but no detailed large scale map emerged until after the city began to tackle the task on the eve of the Second American War of Independence, better known as the War of 1812.

Until then two general views of the city were published by two French trained engineers, Charles Varle and A.P. Folie. Varle’s map, the more popular of the two, became the standard map accompanying the early city directories.

Plan of the City and Environs of Baltimore. Warner & Hanna, (Charles Varle), 1801.

Image from http://1814baltimore.blogspot.com/

The Plan of the City and Environs of Baltimore by Varle, a French refugee by way of Haiti, is a pretty map, especially when colored, and does accurately show the approximate location of the streets as well as the urban sprawl at about 1801 when its last edition was issued. But the map could not be used to plot the expanding street bed and made no effort to delineate the administrative boundaries of the city.

By 1811, matters had gotten so bad with regard to where the streets were meant to go and what limits they placed on how far builders could intrude on their path, that the town leaders, including the legally constituted commissioners for opening streets, desperately needed a map and plan to follow. Hence the City Ordinance of March 25, 1812 “for making a correct survey of the city of Baltimore”, came to pass and announcements were placed in the local newspapers soliciting proposals. Under the city charter of 1797, as the most recent definitive political and administrative history of the city by Matthew Crenson points out,

“Five City Commissioners were appointed [by the Mayor and City Council] to take over the responsibilities of the five special commissioners for street paving. In addition to the commissioners’ existing responsibilities for paving streets and installing pumps, the new municipal commissioners also had to handle the contentious business of establishing the boundaries of city lots.”

It would take a decade until 1822 before the accurate mapping of the city was complete, after considerable wrangling, including a not so pleasant competition between a solitary scientific surveyor, and the well-established compass and chain land surveyors of Baltimore City. In the end science won out, but not without an acrimonious struggle.

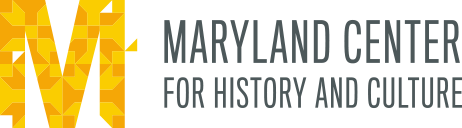

The Bird Transit.

From the collection of the Friends of Independence National Historic Park, Philadelphia, PA.

When Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon were hired by the Calverts and the Penns in the 1760s to survey their mutual boundary, no one challenged their methods and praise was heaped upon the results. The accuracy with which they established a degree of latitude and worked from there to run their line westward was a marvel.

The instruments they used are illustrated and explained in Edwin Danson’s book, Drawing the Line: How Mason and Dixon Surveyed the Most Famous Border in America, and the wonderfully restored Bird transit that Mason and Dixon used is now owned by the National Park Service at Independence Hall in Philadelphia.

In 1798 when the engineers surveying and laying out Fort McHenry utilized what was probably a Ramsden theodolite, a great improvement on the transit, and trigonometry to perfect their work, no one complained, or even commented in the local papers.

It undoubtedly came as a surprise to a 47 year old English surveyor by the name of Thomas Holdsworth Poppleton, newly arrived in Baltimore, that his answer to an advertisement soliciting proposals to survey the city, would meet with such intense opposition from the local surveying community.

Anglican Church of St. George in the East, London, where Thomas Poppleton was baptized.

Image from http://1814baltimore.blogspot.com/

Thomas Holdsworth Poppleton was baptized on July 14, 1765 at the Anglican Church of Saint George in the East in London, still in existence at 14 Cannon St Rd London E1 0BH (+44 20 7481 1345). In 1780, at the age of 15, he was apprenticed to a member of the Honorable Company of Vintners whose motto is Vinum Exhilarat Animum, Latin for Wine Cheers the Spirit. How he got to surveying is not known. Perhaps he enjoyed himself along the way, although by the time he died in Baltimore in 1837, he was apparently a teetotalling Protestant Methodist.

By January 1799 Poppleton was married to an Ann Firth, perhaps the same Ann who was forced to open a confectionery shop in Baltimore in the 1830s to supplement her husband’s then meager earnings. Apparently they had only one child who probably died as an infant after his baptism in 1805, Thomas Holdsworth junior, although there remains some confusion over the mother’s name.

Kings Bench Prison, London, ca 1808.

Image from http://1814baltimore.blogspot.com/

By 1805 Thomas Holdsworth Poppleton also took on his own apprentice (apprentices had to pay for the privilege the munificent sum of £200 pounds-or about $22,000 in 2014 terms), set himself up in business as a house, land, and timber surveyor at the somewhat prestigious address of number 1, Bloomsbury Square, London. About the same time he took on architect Henry Ashley Keeble as a partner which proved to be an unmitigated disaster. In 1807 the partnership was dissolved and Poppleton ended up in King’s Bench Prison as a debtor.

Fortunately for him, he arrived in prison just before debtors in Ireland and England were granted a reprieve by the King and released if they owed less than a thousand pounds.

He remained in the city for brief time, but was pursued by another apprentice who claimed that he had not fulfilled his obligation to train him in the trade. The apprentice describes his problems with his masters in a petition to have his apprenticeship annulled. The court granted his release from Poppleton and Keeble on the basis that both partners were in hiding (actually both ended up in debtors prison).

Keeble, would emerge from debtors prison to go on to a modest career as a London Architect (a few of his townhouses are still extant) and even did some work from London for the wealthiest man in America at the time, Philadelphian William Bingham.

Thomas Holdsworth Poppleton instead chose America to revive his fortunes, arriving in Baltimore by April of 1812 where he opened an office on North Howard Street, and offered to survey the City in response to a notice soliciting proposals that he had read in the newspapers.

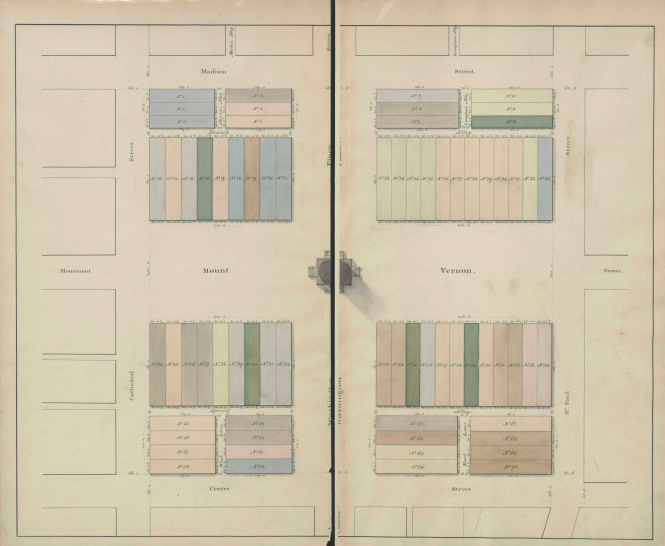

Detail, The Plan of the City of Baltimore as enlarged and laid out under the direction of the Commissioners/Thomas Poppleton, Baltimore, 1822.

Image from http://1814baltimore.blogspot.com/

How he came to choose Baltimore to revive his fortunes is not yet known, but it is possible that he was aware of John Eager Howard’s need for a surveyor of his extensive urban properties, and the city’s desperate need for an accurate survey of its boundaries, streets, and alley ways. The mystery figures in Poppleton’s attraction to Baltimore are the Quaker Assurance broker and friend of the Howards, Joseph Townsend, and Cornelius Howard, Jr., Governor John Eager Howard’s brother. Joseph Townsend, initially a bookbinder and teacher by trade and an early opponent of slavery, established the most successful building insurance company in the city (Baltimore Equitable Insurance Society), running it to his and his family’s benefit for over fifty years from the same location on Baltimore Street. He would prove to be Poppleton’s strongest defender and would oversee the completion of Poppleton’s map, paying the bills and lending his young, nearly blind, son, Richard H. Townsend to assist in the task of laying the permanent boundary stones of the city. Cornelius Howard, Jr., was the brother of Governor John Eager Howard, revolutionary war hero and friend of Washington’s, who owned significant areas of the city and the surrounding countryside including what was to become Mount Vernon Square and the site of the elegant Robert Mills monument to George Washington. Cornelius was a respected land surveyor of the old school of compass and chain who is probably best remembered as a gentleman farmer and breeder of horses who lived to the ripe old age of 91. In the years before Poppleton, he had been called upon to sort out the ancient surveys of the land that encompassed the city and may even have participated in the abortive 1785 attempt to map the town. The surviving survey notes are among his papers.

By 1812, Cornelius Howard, a few years older than Poppleton, was involved in surveying land in the Illinois country and was apparently well regarded as a surveyor by the powers that be in Albany, New York, if only by reputation. He too would come to Poppleton’s defense, and when Poppleton was in effect ridden out of town by a dissenting commissioner and a prominent local land surveyors, recommended him for a prestigious, well-paying assignment in New York City.

On April 10, 1812, from his office on North Howard street, Thomas Holdsworth Poppleton answered the call of the City Commissioners:

“In pursuance of a notice date 3rd April which has appeared in the newspapers of this City, inviting proposals for “making a survey and correct plat of the City of Baltimore agreeably to an Ordinance passed 25th March last.” I offer myself to your notice as being disposed to exert my utmost abilities in performing all the duties imposed upon the artist by the above named ordinance….I beg further to submit that having had much experience in that particular branch of Surveying, I feel myself amply possess’d with the requisite portion of skill.”

The requirement of an ‘artist’ surveyor to do the job has puzzled some historians who do not realize that surveying is an art as much as it is a skill, especially when it comes to depicting the product on paper. It is likely that Joseph Townsend and the Howards were aware of the ‘art’ of the surveyor in the most important of the survey maps of London published by Richard Horwood between 1792 and 1799. As the British Library explains:

“Horwood intended originally to show every house and its number but this was to prove impossible. Although every house is included the numbering was never completed.”

Horwood dedicated this map to the Trustees and Directors of the Phoenix Fire Office, reflecting that the protection of London from fire was at this time the reserve of numerous independent company brigades. The map is coloured, describing parks in green and the London Wall in red. The Tower of London is shown only by outline; Horwood records that: ‘The Internal Parts not distinguished being refused permission to take the Survey’, evidence that a surveyor was not always welcome.

All but one of the Baltimore City commissioners supported the adoption of Poppleton’s plan for surveying Baltimore City. From the beginning commissioner Henry Stouffer and his ally Jehu Bouldin, a well-known local compass and chain surveyor set out to undermine Poppleton’s plan. Why is not clear, except that Bouldin wanted the job, and Stouffer appears to have been an adamant Jeffersonian Democrat/Republican, politically opposed to the Federalist party supported by the Howards.

Poppleton was clearly taken aback by his critics. Hired by the City commissioners, he began his work and soon found himself tricked into stopping to locate stones marking property lines on streets already laid. Although he complained that it was not a part of his contract and that his job was to say where the boundaries of the city lay on the ground and how the streets should run on the ground in the future according to the laws and ordinances that called for them, he agreed to try and find the boundary between James Carey and former mayor James Calhoun’s property on Light Street. It proved a disaster for Poppleton. As his enemies put it “Mr. Poppleton not being able to find any point by course and distance for his compass & chain both appearing to be incorrect. …”

Poppleton was livid and wrote a detailed rebuttal to the Commissioners in which he laid out in an eight page memorandum his ardent belief in the reliability of triangulation and the use of a theodolite (possibly a Ramsden) to produce an accurate survey of the town, all the while debunking the old method of compass and chain.

He begins by asserting that,

“If I understand aright, the order for [my] survey [of Baltimore] originated in an idea that I possessed a talent for such an undertaking founded on an improved & scientific method now in general use in civil & military surveying in Europe… [I was] decoyed out, to perform operations with an instrument I condemn [i.e. the compass]– in a way that is in principal & contrary to my practice… [That] this pitiful underhand mode of proceeding was to be the test of my abilities–to narrow minds it may be apparently correct–from all such I appeal.”

He then proceeded to lambaste the practice of the compass and chain surveyors, particularly the method used by Jehu Bouldin, although not identifying him by name, and outlining in detail with examples his own.

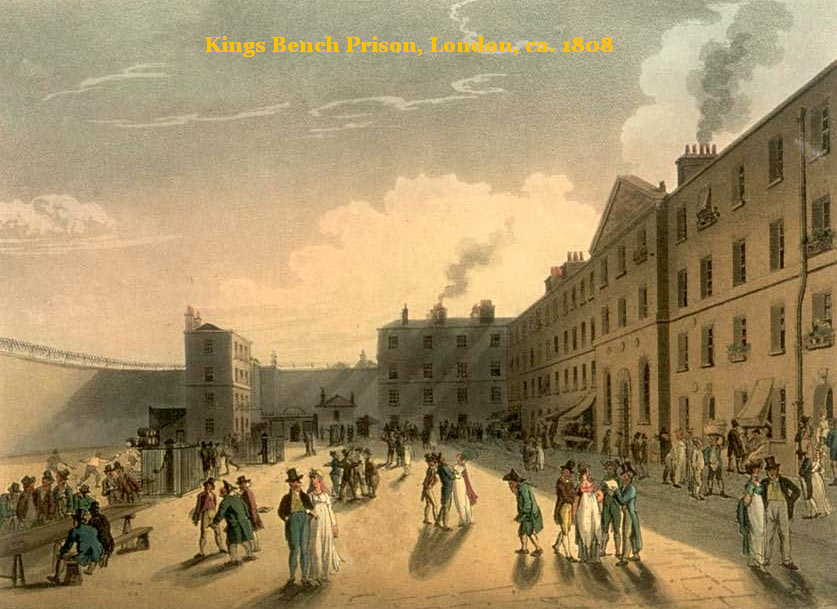

Thomas Jefferson’s Theolodite.

Image from http://1814baltimore.blogspot.com/

After explicitly laying out the inadequacies of compass and chain surveying, especially the inability to close a survey and the vagaries of the compass, particularly in an urban setting with its magnetic variations, he detailed his method of triangulation using an instrument of which he was justly proud.

What Poppleton describes as his principal instrument for accurate surveying is ironically very close, if not an example, of one favored by Thomas Jefferson and possibly purchased in London in the late 1780s when Poppleton was an apprentice.

That the politics of surveying meant that supporters of the Party of Jefferson in Baltimore City in 1812 had little use for Jefferson’s or Poppleton’s theodolite, is understandable. Jefferson was not hailed for his skills as a surveyor but as the retired president and adamant opponent of the Federal party of Hamilton, Adams, and the Howards, Poppleton’s employers. Besides Jehu Bouldin knew where the boundary stones of the streets were buried and felt no need to survey with anything other than a telescope to site a place, a compass to plot direction, and a chain to calculate distance.

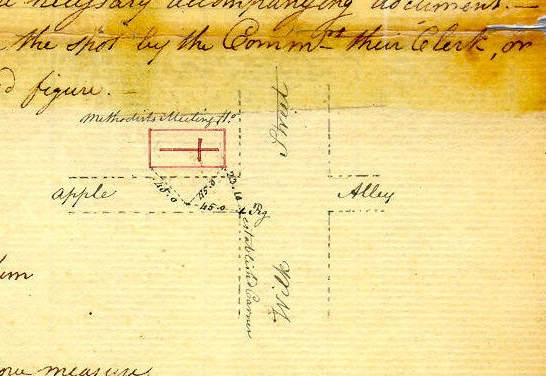

Thomas Poppleton, Sketch of Methodist Meeting House at Apple Alley, Baltimore.

Image from http://1814baltimore.blogspot.com/

In closing his assessment of the accuracy of his methods, Poppleton provides a specific example of how his survey of the streets will be more accurate than that of any compass and chain surveyor Commissioner Stouffer puts forth. He begins with the incident that led to his discontent, explaining why he could not find the existing boundary stones on light street, and concludes with a sketch of his triangulate location of a street corner in Fells Point, across from the African-American church on Apple Alley, perhaps a place chosen in deference to Joseph Townsend, a strong supporter of slavery’s abolition. It would be a church that would feature prominently on his map when it was at last published for the world to admire, and the City to utilize in its expansion outward.

The City Commissioners, influenced by Commissioner Henry Stouffer’s skulduggery, back tracked. The mayor, Edward Johnson, who first supported Poppleton, reacted as politicians often do to Poppleton’s memorandum by suggesting that the City could not afford him (the City commissioners had agreed to give him $3,000 for his map). In Johnson’s words:

“This Gentleman has addressed a long letter to me, explanatory of his intended mode of procedure, which not embracing the provisions of the law [relating to resolving property line disputes], occasions a special reference to the wisdom & decision of the City Council [to hire Jehu Bouldin as the City Surveyor over Poppleton to carry out those functions]. Observing at the same time, that the expenditure of the sum of three thousand dollars (however anxious we may be to encourage artists of superior talent and abilities) unless it can be made to answer a useful & valuable purpose, is not expedient in the present state of the resources of funds of the city.”

In his efforts to unseat Poppleton, Commissioner Henry Stouffer even appealed to Cornelius Howard with regard to evaluating Poppleton’s condemnation of the use of compass and chain surveying. Howard in turn, tactfully as he could, given the political climate, agreed with Poppleton’s assessment of the use of the compass and chain, but the tide had turned against the scientific surveyor. Poppleton quit in disgust in the summer of 1812, as the city became consumed by the advent of war with Great Britain and postponed surveying its streets.

Plan of the city of New-York : the greater part from actual survey made expressly for the purpose (the rest from authentic documents), 1817, Thomas H. Poppleton (Surveyor), Peter Maverick (Engraver). From The New York Public Library.

On the strong recommendation of Cornelius Howard, Poppleton, still a British citizen, left for a prestigious surveying assignment in New York City, announcing that if the city fathers wanted all that he had already done, and wished him to complete the survey, all they had to do was modify his contract, leaving him in peace to do his work, and call him back.

It will never be known for certain how the New York legislature came to pick Cornelius Howard to partner with two famous inventors, Eli Whitney and Robert Fulton, in an attempt to contain the open sewer that was known as Canal Street in lower Manhattan. What survives is a copy of a letter of Poppleton’s dated August 13, 1812, from his office on North Howard Street to William Coleman in New York. He informs the fiery anti-war Federalist editor that he will pursue the recommendation of Cornelius Howard, and a wealthy New York quaker, Thomas Eddy, to replace Howard on the commission to address the problem of Canal Street. Eddy was a strong advocate of a canal through Western New York eventually known as Clinton’s ditch or the Erie Canal. Poppleton told Coleman that he could be in New York in two weeks time, once he finished another legislatively mandated project to survey Pratt Street, the plats for which have survived. William Coleman was the first editor of the The New York Evening Post (today known as the New York Post), chosen by founder Alexander Hamilton, and was outspoken in his opposition to the war against Great Britain. It is possible that Joseph Townsend, Poppleton’s quaker patron and insurance broker knew Thomas Eddy and instigated his recommendation. Both were successful insurance brokers as well as nationally known Quaker businessmen.

It took longer for Poppleton to reach New York than he planned. His principal contact for the project, Alexander Bleecker, another wealthy N. Y. Federalist whose properties would be affected by the study of options for Canal Street, became anxious, but eventually Poppleton arrived and set up an office in his accommodations. It also took longer for his precious theodolite to arrive, but he did get down to business at once, meeting with his co-commissioners, Robert Fulton and Eli Whitney. While most of Poppleton’s Baltimore papers have long since disappeared, his journal for his first New York project has survived, purchased by the New York Public Library in 1905. In it he details his work with the other two commissioners over the period from October 7, 1812, until all three signed off on their plans and recommendations, submitting them to the city and to Governor Clinton in Albany. Poppleton did the survey and the accompanying plats. Robert Fulton prepared the perspective drawings. Whitney attended all the decision meetings and was consulted on the engineering aspects of the proposed solution to the open sewer that was Canal Street. They began with the idea that they would be proposing a canal with sewers underneath, but concluded that the best treatment was to abandon the canal and concentrate on an elaborate covered sewer. The city fathers found their proposal too expensive and over time all of the drawings and plats have disappeared from the City Surveyor’s office, although their advice was eventually taken. Poppleton’s work was exemplary, however, and landed him the post of one of the City Surveyors, and a partnership with another surveyor that brought him significant business including surveying and mapping parts of Brooklyn as well as the opportunity to produce the best survey map of Lower Manhattan published in 1817, that continued to be used in defining streets and property lines well into the 19th century. By the time his map was published he had an office in the New York City Library and to all appearances was there to stay.

Back in Baltimore, the political opponents of the city in the 1816/1817 General Assembly convinced their brethren to expand the city’s boundaries to encompass the outlying precincts containing the majority voters who were democrats, eliminating their impact on Baltimore County politics. The first act of enlargement left the job to the City commissioners to lay out the new boundaries and they turned to Elihu Bouldin to place the boundary stones.

Joseph Townsend and his friends in Baltimore were not pleased. They approached the Federalist controlled legislature the very next session (1817/1818) and secured a new state commission to revive Poppleton’s survey plan and dumping Bouldin. Not only were they commissioned to re-lay the boundary stones, but also they were empowered to mark the corners of the principal streets and to delineate their paths outward on the ground, renaming streets in the process. The city was required to pay for the survey and map, but had no control over who did the survey and what methods were used to produce it. The commission was headed by John Eager Howard, with Joseph Townsend and [5] others. Townsend supervised Poppleton’s work and advanced the money to pay for it out of Baltimore Equitable Society funds, expecting to be reimbursed by the City upon completion.

The chronology of Poppleton’s progress on his survey and map survives among the papers of the Baltimore Equitable Society that were purchased at auction by the Maryland State Archives. He re-commenced his survey and the laying of the perimeter boundary stones in June of 1818, apparently uprooting those previously planted by Jehu Bouldin. Four years and several hundred stones later the survey was complete and his wall map was ready for publication.

Manuscript charting Poppleton’s progress.

Papers of the Baltimore Equitable Society, MSA SC 4645-3-16, Maryland State Archives.

The map proved to be a work of art as well as an accurate depiction of Baltimore’s streets and blocks as they were in 1822, and as they were meant to be developed all the way to the new perimeter of the city. He had to contend with the chaos of existing streets, but straightened and laid their extensions out as best he could with his trusty theodolite and reliance upon triangulation. What he accomplished lays well upon google earth and reflects an accuracy that he promised. The commission had the power to rename streets as the survey progressed and the map reflected at least two private jokes of the surveyor.

Detail, The Plan of the City of Baltimore as enlarged and laid out under the direction of the Commissioners/Thomas Poppleton, Baltimore, 1822.

Image from http://1814baltimore.blogspot.com/

The first was to list the Apple Alley Methodist church as the first among Baltimore Churches listed on the map proper, the church location and street that Poppleton had included as his example of the accuracy of his surveying method. The second was to obliterate the street name, Still-House street, just east of Jones Falls, on which his rival, Jehu Bouldin had long maintained his offices, renaming it a continuation of “Front Street.”

Instead of the original $3,000 that Poppleton proposed as the fee for his services and the resulting map, the project cost nearly $6,500 with interest, much of the cost being advanced by Joseph Townsend and Baltimore Equitable. When the bills were submitted to the Mayor and City council for reimbursement, another firestorm erupted over the cost and the quality of the work which emanated from the Stouffer/Bouldin faction on the council.

The reaction of the council was too much for Townsend and Poppleton. The milder response came from Poppleton who published his observations in the local press with a letter to the editor that omitted names found in the original manuscript:

“Sir: by the Morning Chronicle of the Tuesday last [March 18, 1822], I learned for the first time at a doubt existed in your Branch of the City Council relative to the correctness of the Plat returned by the Commissioners, and made by me under their direction.”

He went on to explain that the issue was the scale used in the map, and that the accompanying plats filed with the city provided both accurate scale and explicit detail.

Joseph Townsend was not as gentle in his scathing letter to the council. The First Branch of the City Council was so taken aback that it recorded in its journal that they returned Townsend’s letter to the second Branch (Where Henry Stouffer’s relative served) with the comment,

“We beg leave to suggest the propriety of returning it to Mr. Townsend as being a paper unfit to be recorded in the journals of the City Council.”

Townsend had a right to be angry. Poppleton did what he said he would and produced a map that the City came to adopt as its own, with an expanded edition in the 1850s that was used for Baltimore’s unique system of land transfer and recordation, the block book system, whereby Poppleton’s city blocks were numbered on his map and all recorded land transaction from 1851 forward were recorded geographically by block.

Unfortunately over time the block book system broke down through poor administration by the court of record and the city, but for the rest of the nineteenth century until well into the twentieth it served surveyors and the public admirably. Recently it was supplanted altogether by an automated on-line automation of land recordation created by the Maryland State Archives that placed the surviving block books and the related recordations on line making title searches for lot descriptions infinitely easier for developers and their surveyors, although the nightmare of ownership and title entangled in ground rents has not been effectively addressed and remains a thorn in the side of re-development of the streetscapes of the city. Baltimore like Birmingham in England used the leasing of property at interest (ground rents) to free capital for building on the property. As long as the ground rent was paid the buildings could be separately bought and sold. If it wasn’t, technically anything on the property reverted to the property owner. Over the years the ownership of the ground rents and the above ground property owners became a quagmire of who owned what. In some instances ground rents were being double charged because of overlooking property divisions within estates to the point that some property owners in a block, instead of being charged with half the ground rent for the block, were each charged the ground rent for the whole block. The Legislature once again tried to act in what it perceived the best interest of the city and tried to abolish ground rents altogether by legislative fiat. The case is still before the courts.

In the aftermath of the publication of his map, Poppleton did not have to worry about ground rents. Instead he helped create them, particularly with the work he did in surveying the John Eager Howard estate. When Howard’s daughter contested the division of her father’s estate, by another act of the Legislature intended to resolve the differences, Thomas Poppleton was hired to survey and lay out a fair distribution with clearly defined streets such as what he did with the Mount Vernon Square district that is today the home of Robert Mill’s monument to George Washington.

Poppleton went on to work for the B&O railroad and its efforts to construct a main line on Pratt Street, but not before toying with bankruptcy in 1830, when to do so he also had to apply for citizenship, sponsored by none other than Joseph Townsend.

Poppleton’s plat of the Howard Estate made for Sophia Howard Read.

Image from http://1814baltimore.blogspot.com/

Little of Poppleton’s post map survey work has survived, save the exquisite plats he drew for Sophia Howard Read’s efforts to get a more equitable share of her father’s estate. While his efforts to survey for the B&O are praised in the press, the plans he produced from his surveys have disappeared, although the street that runs by the B&O roundhouse still bears his name today as he plotted it on his map. It is not often if ever that a surveyor is able to name a street after himself, but why not? Surely he deserved it.

Poppleton did participate in the enthusiasm for canals to improve the city’s prospects for trade. He surveyed the elevations and path for a proposed canal from the Susquehanna to Baltimore for which Fielding Lucas, a local printer of fine maps ultimately drew upon for the copies now located in the Maryland and Pennsylvania Archives.

In all, Poppleton’s last years were spent in apparent near poverty. When he died of ‘old age’ at 72 in 1837, only brief notice was made of his passing. By then his wife Ann had opened a confectionery shop as a means of support, and at his death there was not enough property for an inventory of anything worth distributing. What happened to his treasured theodolite and the bulk of his papers is unknown, although it appears that the Bouldin family acquired some, including the original of his plat of Pratt Street that he completed just before leaving for New York in 1812. Indeed by 1912 Jehu Bouldin’s granddaughters suggested they owned Poppleton’s theodolite, a picture of which was published in The Baltimore Sun. It wasn’t. Instead it was a later model probably used by their father, Alexander Bouldin, who came to adopt Poppleton’s approach to surveying. The irony remains that the family would appear to think so highly of the memory of Poppleton by 1912, but his instrument remains at large, if not lost altogether.

Baltimore’s first Custom House located at S. Gay Street.

Detail, This Plan of the City of Baltimore as enlarged and laid out under the direction of the Commissioners appointed by the General Assembly of Maryland in February 1818, Thomas Poppleton, 1823 (1852), Large Map Collection, MdHS.

Anyone interested in plotting the history, growth and development of Baltimore from 1822 to the present cannot escape admiring and utilizing Thomas Poppleton’s survey map of the City. It places well on the existing streets of Google Earth and can be used to aid in the geo-referencing of the physical change of the city over time as well as the history of the homes, institutions, and businesses it locates and identifies. Around its border are inset illustrations of public monuments, fountains, churches, banks and businesses as of 1822, with historical images at its base of the first images and layout of the the town, and the bombardment of Fort McHenry whose battlements had been placed with aid of another theodolite a decade and half before Thomas Holdsworth Poppleton came to town to battle his land surveyor peers over how best to measure and delineate the city streets. May his tarnished memory regain some of the lustre it deserves in the grand tradition of such scientific surveyors as Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon, pushing back on those who believe Poppleton’s blocks were too large and his streets unaccommodating to the contours of the land. Those issues were more a matter of the city permitting development of the alleys within the blocks with inferior housing for the black and immigrant labor families, and the lack of a comprehensive sewer and water infrastructure, something the city did not accomplish until after the disastrous fire of 1904, and then only with massive State financing paid for by all Maryland taxpayers.

As a tribute to Thomas Holdsworth Poppleton, it is hoped that funding can be found to restore one of his maps in very bad condition that the Maryland State Archives has acquired. It has a remarkable ownership history of its own, as well as being a first edition, if not the first. If anyone is interested in helping with its resurrection, I can supply a treatment report and costs. (Edward C. Papenfuse)

Dr. Edward C. Papenfuse is the retired Maryland State Archivist and Commissioner of Land Patents. This piece originally appeared on Thomas Poppleton’s Baltimore, 1812-1837, Dr. Papenfuse’s personal blog devoted to telling Poppleton’s story and the stories of those who lived and worked in and from Baltimore.